More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

August 21 - September 17, 2024

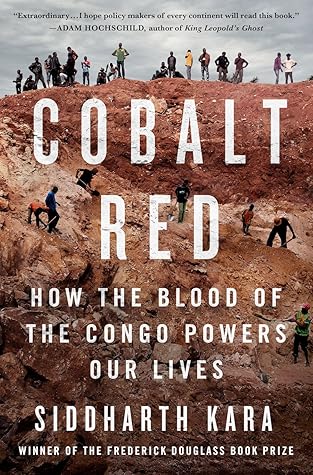

Our daily lives are powered by a human and environmental catastrophe in the Congo.

Bedsheets are used as front doors, except at one home where I saw an American flag being used.

It is tempting to point the finger at local actors as the agents of the carnage—be it corrupt politicians, exploitative cooperatives, unhinged soldiers, or extortionist bosses. They all played their roles, but they were also symptoms of a more malevolent disease: the global economy run amok in Africa. The depravity and indifference unleashed on the children working at Tilwezembe is a direct consequence of a global economic order that preys on the poverty, vulnerability, and devalued humanity of the people who toil at the bottom of global supply chains. Declarations by multinational

...more

She was sixty-nine years old, the oldest person I ever interviewed in the Congo.

The cobalt excavated from the KCC mine by children like Archange made its way safely up the chain into our phones and cars, while the risks associated with scrounging it out of the pit were borne solely by the residents of Kapata. Without the income from Archange’s work, his family was struggling. He felt guilty that he had become a burden to his parents and admitted that he had suicidal thoughts. “I sit in this wheelchair while my family works so hard. I wish I could help them, but I cannot do anything. I cannot even dress myself. I cannot bear living anymore.”

She had been thrown to a pack of wolves by a system of such merciless calculation that it somehow managed to transform her degradation into shiny gadgets and cars sold around the world. The consumers of these devices, were they to stand next to Elodie, would appear like aliens from another dimension. Nothing in form or circumstance would bind them to the same planet, aside from the cobalt that flowed from one to the other. Elodie soon grew weary of my presence.

They explained that the organization had received several million dollars in support from Apple, Microsoft, Google, Dell, and a commodity trading company called Trafigura to set up the model site in Mutoshi, and a certain image had to be maintained. The purpose of the site was to provide a clean source of cobalt for CHEMAF customers, which included the donors. Most of the mineral supply from CHEMAF was sent to Trafigura, which was also the primary corporate partner of the model site.

Ikolo estimated that a tunnel collapsed every month in Kasulo. He said everyone knew when it happened: “We hear the news the same day. We console the families as we hope they will console ours.”

The people whose ancestors were once forced to measure their lives in kilos of rubber were now forced to measure their lives in kilos of cobalt.

hope in the Congo is like a hot coal—take hold, and it will scald you to the bone.

The biggest problem faced by the Congo’s artisanal miners is not the gun-toting soldiers, unscrupulous Chinese buyers, exploitative mining cooperatives, or collapsing tunnels. These and other antagonists are but symptoms of a greater menace. The biggest problem faced by the Congo’s artisanal miners is that stakeholders up the chain refuse to accept responsibility for them, even though they all profit in one way or another from their work.

The path forward cannot, however, follow the typical “flash-in-the-pan” model of addressing human rights violations in global supply chains. All too often, attention will run hot for a brief period, new programs will be announced by corporations and governments, and once the eyes of the world shift elsewhere, conditions will revert to business as usual.