More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

March 29 - March 31, 2024

The price of the batteries was more expensive than I would have imagined—two dollars (roughly one day’s income) for a pack of four AA batteries. The price seemed particularly exorbitant since they were living right next to one of the largest battery-component metal-making mines in the world.

Can any company at the top of the chain legitimately suggest that the cobalt in their devices or cars did not pass through a village marketplace like this?

Guilt took hold as my thoughts turned to Gloire, Marline, Nikki, Chance, Kiyonge, Kisangi, Priscille, and so many others. Their situations may not have been as extreme as Makano’s when I encountered them, but that was only because I met them at different points on the same journey to the same dismal terminus.

understood at last how the people of the Congo survived their daily torment—they loved God with full and fiery hearts and drew comfort from the promise of salvation.

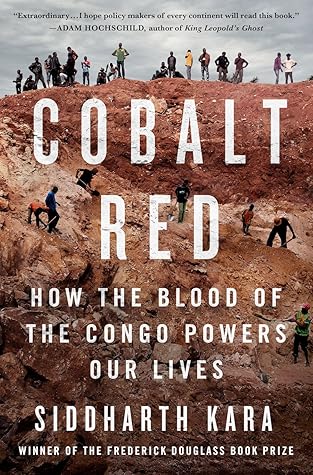

More than fifteen thousand men and teenage boys were hammering, shoveling, and shouting inside the crater, with scarcely room to move or breathe.

The pit was not dirt and stone—it was a solid mountain of rock and heterogenite being chiseled and hammered into pebbles by raw human force.

I could only observe as this sea of humanity matched brute force against the unforgiving rock.

but at the bottom of trillion-dollar supply chains during the modern era?

the Congolese people were being pushed over the cliff’s edge by foreign mining companies that kept appropriating more of their land each year.

The Congolese government directly contributed to the crisis by auctioning off massive parcels of land for billions of dollars and passively sitting back to collect concession fees, royalties, and taxes.

my heart would cry when I saw what the mining companies had done to the forests and rivers.

FARDC soldiers patrol the area and leer at young women.

Bedsheets are used as front doors, except at one home where I saw an American flag being used.

Perhaps the most important thing to know about Tilwezembe is that industrial operations were formally ceased at the mine in 2008. Not long after, artisanal mining took over.

if someone who works at Tilwezembe or Lac Malo or Kasulo speaks to someone like you, they will be shot in the night, and their body will be left on the street to instruct anyone else on the consequences of opening their mouths.”

Campaigns of violence and intimidation work up to a point, and the point at which they no longer work is the moment a person feels they have nothing left to lose.

“Now I know what that dog felt like,” Muteba said. “I wish I had been brave enough to kill it.”

textbook definition of forced labor under international law.

debt bondage

Threats of violence, eviction from the work site, and the lack of any reasonable alternative kept the children ensnared in the system of bondage. In essence, they were child slaves.

Kosongo pulled up his shorts and showed me the stubs that remained of his legs. His eyes moistened, and his lips began to quiver. He placed his hands atop his thighs, yearning for what was missing. “I used to play football [soccer] every Sunday. I was very good.”

rage, sorrow, and guilt.

The depravity and indifference unleashed on the children working at Tilwezembe is a direct consequence of a global economic order that preys on the poverty, vulnerability, and devalued humanity of the people who toil at the bottom of global supply chains.

As we parted ways, Augustin had this to say, “Please tell the people in your country, a child in the Congo dies every day so that they can plug in their phones.”

Look up Kolwezi on Google Earth and zoom

Time-lapse satellite images of Kolwezi from 2012 to 2022 show that the “brown” around the city spread like a tsunami, devouring everything in its path.

Kolwezi is by far the most heavily polluted city in the southeastern provinces. Breathing hurts. Looking burns.

It would not be a stretch to suggest that much of the EV revolution rests on the weary shoulders of some of the poorest inhabitants of Kolwezi, yet few of them have the benefit of even the most basic amenities of modern life, such as reliable electricity, clean water and sanitation, medical clinics, and schools for children.

People ask, why are the children working in the mines? My grandchildren are there now. Would you rather they starve? Many of the children lost their parents. Sometimes a woman will marry again and the man chases the children out of the house. What are those children supposed to do? They can only survive by digging.

Our leaders only care for themselves.

“Every day people are dying because of the cobalt. Describing this will not change anything.”

the horrible beauty of an open-pit copper-cobalt mine.

I marveled at his adroit movements, but I could not help but wonder what kind of damage was being done to his ankles, knees, back, and neck … assuming he lived long enough for the consequences to make themselves known.

Mosquitoes do not drink the blood of the people who work here.’”

The cobalt excavated from the KCC mine by children like Archange made its way safely up the chain into our phones and cars, while the risks associated with scrounging it out of the pit were borne solely by the residents of Kapata.

It is the tragic inheritance of all who enter the world in the Congo. The ailing infant on Elodie’s back will inherit it

they asserted that the international community also had to appreciate that in the Congo, a fifteen-year-old boy would consider himself to be a grown man. Europeans and Americans were not in a position to determine what constituted adulthood in the Congo. A fifteen-year-old already had to provide for his family as an adult would, I was told.

The fact that families across the DRC are faced with the non-choice of putting a child in school or putting them to work so that the family can survive means that those families have been abandoned by the Congolese state just as much as they have been abandoned by the global economy.

In essence, the CDM model site placed a thin veneer of formality over a highly dangerous and exploitative system that seemed designed to maximize production and minimize worker well-being, safety, and income. Even the paltry expense of uniforms and safety equipment was eschewed.

the monthly fees per child required to keep Congolese children in school and out of mines was equal to two Primus beers at Taverne La Bavière.

“All I can add in my solitude, is, may Heaven’s rich blessing come down on everyone, American, English, or Turk, who will help to heal this open sore in the world.”

Fate spared him the tragic truth—his efforts to open the interior of Africa to commerce and Christianity led to immeasurable suffering of the people he so loved. In no place has that suffering been greater than in the Congo.

Nothing matters here but the resource; people and environment are disposable.

The essence of Kasulo is a devil’s gamble: tunnel diggers risk their lives for the prospects of riches. Mind you, the “richest” income I documented in Kasulo was an average take-home pay of $7 per day. There are spikes to $12 or even $15 when a particularly rich vein of heterogenite is found. That is the lotto ticket everyone is after. The most fortunate tunnel diggers in Kasulo earn around $3,000 per year. By way of comparison, the CEOs of the technology and car companies that buy the cobalt mined from Kasulo earn $3,000 in an hour, and they do so without having to put their lives at risk

...more

We know the tunnel might collapse. We are not stupid. We pray before we go down. We focus on our work. It is in God’s hands if we live.”

“There is no other work here. Cobalt is the only possibility. We go down the tunnel. If we make it back with enough cobalt, our worries are finished for one day.”

The people whose ancestors were once forced to measure their lives in kilos of rubber were now forced to measure their lives in kilos of cobalt.

That is the “disaster” that Gloria, the student in Lubumbashi, warned about. Once the resources have been looted, the Congolese people will be left with nothing but worthless dirt and empty stomachs. In the interim, the prospect of earning five or ten dollars a day beckoned thousands of diggers like Mutombo into the tunnels.

shaft, Mutombo described the tunnel-digging process in more detail. The first step was called kufanya découverte, a mash-up of Swahili and French that meant “to do the discovery.”