More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 2 - December 15, 2024

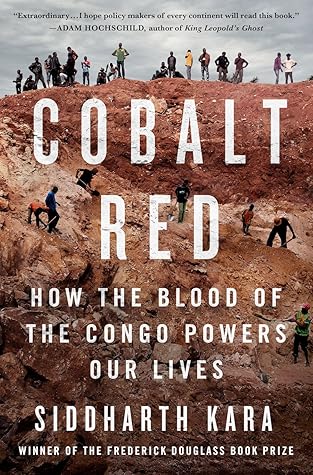

The Katanga region in the southeastern corner of the Congo holds more reserves of cobalt than the rest of the planet combined.

The harsh realities of cobalt mining in the Congo are an inconvenience to every stakeholder in the chain. No company wants to concede that the rechargeable batteries used to power smartphones, tablets, laptops, and electric vehicles contain cobalt mined by peasants and children in hazardous conditions.

In all my time in the Congo, I never saw or heard of any activities linked to either of these coalitions, let alone anything that resembled corporate commitments to international human rights standards, third-party audits, or zero-tolerance policies on forced and child labor. On the contrary, across twenty-one years of research into slavery and child labor, I have never seen more extreme predation for profit than I witnessed at the bottom of global cobalt supply chains.

Our daily lives are powered by a human and environmental catastrophe in the Congo.

There is no known deposit of cobalt-containing ore anywhere in the world that is larger, more accessible, and higher grade than the cobalt under Kolwezi.

At no point in their history have the Congolese people benefited in any meaningful way from the monetization of their country’s resources. Rather, they have often served as a slave labor force for the extraction of those resources at minimum cost and maximum suffering.

The battery packs in electric vehicles require up to ten kilograms of refined cobalt each, more than one thousand times the amount required for a smartphone battery. As a result, demand for cobalt is expected to grow by almost 500 percent from 2018 to 2050,3 and there is no known place on earth to find that amount of cobalt other than the DRC.

As of 2022, there is no such thing as a clean supply chain of cobalt from the Congo. All cobalt sourced from the DRC is tainted by various degrees of abuse, including slavery, child labor, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and toxic working conditions, pathetic wages, injury and death, and incalculable environmental harm.

Despite being home to trillions of dollars in untapped mineral deposits, the DRC’s entire national budget in 2021 was a scant $7.2 billion, similar to the state of Idaho, which has one-fiftieth the population. The DRC ranks 175 out of 189 on the United Nations Human Development Index. More than three-fourths of the population live below the poverty line, one-third suffer from food insecurity, life expectancy is only 60.7 years, child mortality ranks eleventh worst in the world, access to clean drinking water is only 26 percent, and electrification is only 9 percent.

We are rarely asked, if ever, to confront the untold suffering that has been endured by Africa.

Soon after, the Manhattan Project identified Shinkolobwe as the ideal source for the high-grade uranium required to build an atomic bomb.

The depravity and indifference unleashed on the children working at Tilwezembe is a direct consequence of a global economic order that preys on the poverty, vulnerability, and devalued humanity of the people who toil at the bottom of global supply chains.

“Please tell the people in your country, a child in the Congo dies every day so that they can plug in their phones.”

Kolwezi is the mangled face of progress in Africa. The hunt for cobalt is all.

The fact that families across the DRC are faced with the non-choice of putting a child in school or putting them to work so that the family can survive means that those families have been abandoned by the Congolese state just as much as they have been abandoned by the global economy.

The lack of government support of public education in the DRC is an inexplicable failure that severely exacerbates levels of poverty and child labor in the country.

Kasulo is also the face of everything that is wrong with the global economy. Nothing matters here but the resource; people and environment are disposable.

“Our children are dying like dogs.”

This was the final truth of cobalt mining in the Congo: the life of a child buried alive while digging for cobalt counted for nothing. All the dead here counted for nothing. The loot is all.

How can a sustainable future be built through sacrificing the very bearers of that future, through depriving children’s well-being, and worse even, through depriving children the right to be?

History will one day have its say; it will not be the history taught in the United Nations, Washington, Paris, or Brussels, however, but the history taught in the countries that have rid themselves of colonialism and its puppets.