More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In all my time in the Congo, I never saw or heard of any activities linked to either of these coalitions, let alone anything that resembled corporate commitments to international human rights standards, third-party audits, or zero-tolerance policies on forced and child labor.

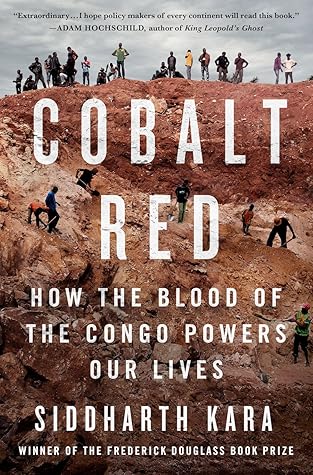

Our daily lives are powered by a human and environmental catastrophe in the Congo.

There are roughly forty-five million people around the world directly involved in ASM, which represents an astonishing 90 percent of the world’s total mining workforce. Despite the many advancements in machinery and techniques, the formal mining industry relies heavily on the hard labor of artisanal miners to boost production at minimal expense. The contributions from ASM are substantial, including 26 percent of the global supply of tantalum, 25 percent of tin and gold, 20 percent of diamonds, 80 percent of sapphires, and up to 30 percent of cobalt.

At no point in their history have the Congolese people benefited in any meaningful way from the monetization of their country’s resources. Rather, they have often served as a slave labor force for the extraction of those resources at minimum cost and maximum suffering.

As of 2022, there is no such thing as a clean supply chain of cobalt from the Congo. All cobalt sourced from the DRC is tainted by various degrees of abuse, including slavery, child labor, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and toxic working conditions, pathetic wages, injury and death, and incalculable environmental harm.

The largest lithium-ion battery manufacturers in the world are CATL and BYD in China; LG Energy Solution, Samsung SDI, and SK Innovation in South Korea; and Panasonic in Japan. In 2021, these six companies produced 86 percent of the world’s lithium-ion rechargeable batteries, with CATL alone holding a one-third global share.6 Most of the cobalt in these batteries originated in the Congo.

In 2010, a Chinese consortium called SICOMINES repaved the road as part of an agreement brokered by Joseph Kabila, through which China managed to corner most of the global cobalt market before anyone knew what happened. It was one of many infrastructure-for-resources agreements that China has negotiated across the African continent.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, both major creditors to the DRC, were not pleased with the new debt load on the Congo and the “other means” clause in the agreement, particularly if it led to the loss of collateralized mining assets on their loans. The IMF and World Bank pressured Kabila to renegotiate terms. In December 2009, the “other means” clause of the agreement was removed, and the total loan amount was reduced from $9 billion to $6 billion. Under the new terms, SICOMINES agreed to pave 6,600 kilometers of road and to build two hospitals and two universities in

...more

President Kabila hailed the SICOMINES agreement as the “deal of the century” and moved quickly to profit from it. Kabila established a private firm called Strategic Projects and Investments (SPI), which received money from a range of Chinese projects, including the tolls paid by trucks that crossed the border at Kipushi after the new road was built. An investigation by Bloomberg revealed that SPI collected tolls of $302 million between 2010 and 2020, and that this was just one of the many Chinese deals through which Kabila and his family profited.

Crucially, the SICOMINES deal is exempt from taxes until infrastructure and mining loans are fully repaid, which means that the DRC will not receive meaningful income from the deal for many years to come.

“I thank God for taking my babies,” she said. “Here it is better not to be born.”

In the aftermath of the UN’s investigation, Bredenkamp pulled out of the scheme and sold Tremalt for $60 million to an Israeli American businessman named Dan Gertler, who already owned diamond and copper mines in the DRC. Gertler was a childhood acquaintance of Laurent Kabila’s son Joseph, who helped him purchase his first diamond concession in the Congo in 1997. Gertler also paid Laurent Kabila $20 million for a monopoly on all diamond trading in the DRC beginning in September 2000.

From the early 1500s until the end of the slave trade in 1866, one-fourth of the 12.5 million slaves stolen from Africa and shipped across the Atlantic would depart from Loango Bay.

Livingstone survived twenty-seven bouts of malaria thanks to his discovery of the ameliorative properties of quinine.

Quinine proved to be the first of two crucial developments that facilitated European colonization of Africa. The second development involved boiling water. Beginning in the 1850s, the steam engine revolutionized transport. Steamboats carried goods quickly and less expensively across rough seas. They could also forge upstream to allow exploration of rivers into the African continent.

Stanley pressed into the upper Congo and passed seven cataracts on February 7, 1877, at a place he named Stanley Falls

It was here that Stanley heard a local tribe call the river ikuta yacongo. He realized the Lualaba River was not the source of the Nile. It was the Congo River.

Stanley’s escapades negotiating treaties for the AIC involved the first time that batteries played a role in the exploitation of the Congolese people.

None of the tribal leaders fully understood that they were ceding authority of their lands to the AIC, and they certainly could not read the language in which the agreement was written. Nevertheless, Leopold had what he needed to make the case that the Congo was his at an imperialist extravaganza called the Berlin Conference.

Farther north, the Belgians sold a seventy-five-thousand-square-kilometer concession of rain forest filled with palm oil trees to the Lever brothers, whose new soap recipe required palm oil. Following Leopold’s model, the Lever brothers used forced labor in the extraction of palm oil under a quota system. The riches they generated helped build the multinational powerhouse Unilever.

There were two buyers of cobalt at Musompo that were of particular interest to me—CDM and CHEMAF. These were the two companies that operated the two model sites for artisanal mining in Lualaba Province. Being a model mine was supposed to mean safe working conditions for artisanal miners, no child labor, fair wages, no dangerous tunnel digging, and above all, ironclad assurances that cobalt mined from the sites was never mixed with cobalt from any other source. These declarations were meant to assure the buyers of their cobalt that their supply chains were untainted by child labor or other

...more

Sixty-three men and boys were buried alive in a tunnel collapse at Kamilombe on September 21, 2019. Only four of the sixty-three bodies were recovered. The others would remain forever interred in their final poses of horror. No one has ever accepted responsibility for these deaths. The accident has never even been acknowledged.

This was the final truth of cobalt mining in the Congo: the life of a child buried alive while digging for cobalt counted for nothing. All the dead here counted for nothing. The loot is all.