More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

June 19 - October 22, 2023

People with Asperger’s don’t access or show feelings, certainly not to this extent. I’d never seen such an unbridled display of raw emotion. I

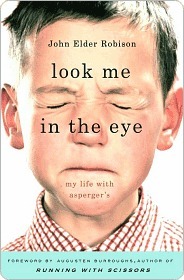

Asperger’s syndrome isn’t all bad. It can bestow rare gifts. Some Aspergians have truly extraordinary natural insight into complex problems. An Aspergian child may grow up to be a brilliant engineer or scientist. Some have perfect pitch and otherworldly musical abilities. Many have such exceptional verbal skills that some people refer to the condition as Little Professor Syndrome. But don’t be misled—most Aspergian kids do not grow up to be college professors. Growing up can be rough.

And Asperger’s is turning out to be surprisingly common: A February 2007 report from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that 1 person in 150 has Asperger’s or some other autistic spectrum disorder. That’s almost two million people in the United States alone.

Asperger’s is not a disease. It’s a way of being. There is no cure, nor is there a need for one. There is, however, a need for knowledge and adaptation on the part of Aspergian kids and their families and friends.

People with Asperger’s or autism often lack the feelings of empathy that naturally guide most people in their interactions with others.

The worst of it was, my teachers and most other people saw my behavior as bad when I was actually trying to be kind.

Successful conversations require a give and take between both people. Being Aspergian, I missed that. Totally.

Machines were never mean to me. They challenged me when I tried to figure them out. They never tricked me, and they never hurt my feelings. I was in charge of the machines. I liked that. I felt safe around them. I also felt safe around animals, most of the time. I petted other people’s dogs when we went to the park. When I got my poodle, I made friends with him, too.

After my father graduated, it was time for him to find a job. The one he picked was all the way across the country, in Seattle, Washington. It took us a whole month to drive there, in our black VW Bug. I really liked that VW. I still have a picture of myself standing by the front bumper. I used to crawl into the well behind the backseat to hide. I’d look out the back window at the sky and imagine I was flying through space.

I liked squeezing myself up tight in a tiny ball when I was little, hiding where no one could see me. I still like the feeling of lying under things and having them press on me. Today, when I lie on the bed I’ll pile the pillows on top of me because it feels better than a sheet. I’ve heard that’s common with autistic people. I was certainly happy back there in the VW, curled up in a little ball on that scratchy gray carpet.

I was happy to discover that there were woods behind our apartment in Seattle. I liked it in the woods. When I was sad, I would go there and sit and think, and I would do woodsman things. That always made me feel better.

Of course, kids always think they know the answers. The difference in my case was that most of the time, I actually did. Even at five, I was beginning to understand the world of things better than the world of people.

I had learned something from my humiliations at the hands of Ronnie Ronson and Chuckie and all the other kids I’d tried and failed to make friends with. I was starting to figure out that I was different. But I had a positive outlook. I would make the best of my lot in life as a defective child.

I was so used to living inside my own world that I answered with whatever I had been thinking.

I have since learned that kids with Asperger’s don’t pick up on common social cues. They don’t recognize a lot of body language or facial expressions. I know I didn’t. I only recognized pretty extreme reactions, and by the time things were extreme, it was usually too late.

It was very different from picking up the dog. My own little brother. I was very excited, but I was careful not to show it, so they wouldn’t take him away from me.

I didn’t know it myself at that time, but for some reason I had a hard time with names, unless I made them up.

As I moved through school as another marginal kid, my dad and my teachers started forecasting my future. They told me I would never amount to anything. They said I was headed for a career pumping gas or jail or the Army—if they would take me. I was contrary and I would not apply myself. But I’d show them.

I knew they thought it was bad for me to be smiling, but I didn’t know why I was grinning, and I couldn’t help it. I didn’t feel joy or happiness. At the time, as I approached my teenage years, it was hard to figure out exactly what I did feel. And I felt powerless to react any differently.

For much of my life, being different equated to being bad, even though I never thought of myself that way.

But it all falls apart if I hear something that elicits a strong emotional reaction from me that is different from what people expect. In an instant, in their eyes, I turn into the sociopathic killer I was believed to be forty years ago.

Caring—or pretending to care—about other people is a learned behavior.

If I hear of something bad happening to one of them, I feel tense, or nauseous, or anxious. My neck muscles cramp. I get jumpy. That, to me, is one kind of empathy that’s “real.”

That’s another kind of empathy. I didn’t have to fix the car. I could have played dumb and she’d never have been any the wiser. I would not have fixed it for anyone besides my mother. But I felt a need to help because a family member was in trouble. I

As I got older, I found myself in trouble more and more for saying things that were true, but that people didn’t want to hear. I did not understand tact. I developed some ability to avoid saying what I was thinking. But I still thought it. It’s just that I didn’t let on quite so often.

I read all the time, and I was learning all sorts of new things. In fact, I kept the more interesting volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica next to my bed. I knew my tractors or dinosaurs or ships or astronomy or rocks or whatever else I was studying at that moment.

As I got older and smarter, my pranks became better, more polished. More sophisticated. Sometimes my stories would acquire a life of their own.

Our father would have been enough for any family, but we had my mother, too. By this time, she had begun the slow slide into madness that would eventually send her to the Northampton State Hospital in restraints.

Down South, they don’t say guitar. They say git-tar. And they don’t say violin. They say fiddle. “That there’s a bass, sonny,” the salesman said.

My ideas worked. My Fender amp got louder, a lot louder, and it began to sound hotter. I took it to some local shows and had the musicians play it against their own amps. It ran circles around most of them.

And, most remarkably, I developed the ability to translate those waves I saw in my mind into sounds I imagined in my head, and those imagined sounds closely matched what emerged from the circuits when I built them.

No one knows why one person has a gift like this and another doesn’t, but I’ve met other Aspergian people with savantlike abilities like mine. In my opinion, part of this ability—which I seem to have been born with—comes from my extraordinary powers of concentration. I have an extremely sharp focus. I

For the first time in my life, I was able to do something that grown-ups thought was valuable. I may have been rude. I may not have known what to say or do in social situations. But if I could fix five tape recorders in an afternoon, I was “great.” No one except my grandparents had ever called me that before.

Another thing I found in the AV room was the girl who became my first wife. Mary Trompke was another shy, damaged kid like me. Something about her fascinated me. She was very smart, but she didn’t say much.

I thought she was cute—short and solid, with dark hair in pigtails. I was totally smitten. She was the first person I had met who could read as fast as me, maybe even faster. And she read exciting things: books by Asimov, Bradbury, and Heinlein. I immediately began reading them, too. But I was far too shy and insecure to ever tell her how I felt about her. So we just talked and read and fixed tape recorders and walked into town every day. That was Aspergian dating, circa 1972.

I was pleased and proud, but I was careful not to let on, because I knew by this time that real men did not show emotions over things like this.

When I was fourteen, my guidance counselor said, “John, some of your tricks are sick. They are evil. They indicate deep-seated emotional problems.” It was true that some of my pranks had taken on a nasty edge. My sadness at how other kids had treated me all my life had turned to anger. If I had not found electronics and music, I might well have come to a bad end.

I want a professional to tell me what to do, I thought. I can go home and read the Bible some other time.

Along with bobbing and weaving, I was also frequently criticized or ridiculed for inappropriate expressions. These attacks seemed to me to come out of the blue, and they usually made me want to run off and hide.

In the first sixteen years of my life, my parents took me to at least a dozen so-called mental health professionals. Not one of them ever came close to figuring out what was wrong with me. In their defense, I will concede that Asperger’s did not yet exist as a diagnosis, but autism did, and no one ever mentioned I might have any kind of autistic spectrum disorder.

I never understood how some guys did things like that. A girlfriend for a week, just like that. I was too shy even to talk to them.

One of the policemen drove me back to the villa, where I picked up our rental car. It was a Jeep-like rig called a Morris Moke. Mokes are a lot of fun, and a tropical island like Montserrat was the ideal place to have one. Prior to my arrest, I had even gotten a Montserrat driver’s license for the thing. I was kind of proud of it.

The next day, our vacation came to an end. I said good-bye to Willie and his iguana, and we flew home on a World War II surplus DC-3 with no door and with chickens in cages stacked in the aisle. Skimming a thousand feet above the ocean, we headed back to the snow, the spring thaw, and the mud. And our next show, Friday night at the Rusty Nail. A few years later, most of Montserrat vanished when the volcano erupted. The villa, the jail, the roads … all gone.

The first to hire me was Britannia Row Audio, the sound company that Pink Floyd had formed to rent out their equipment when they were not on tour.

It took me a moment to figure out what “from the U.K.” meant. For some reason, British musicians I spoke to were never “from England.” They were always “from the U.K.”

When I was done, we hauled the repaired amplifiers onto the soundstage. One by one, we hooked them into the PA. Seth ran each one up to full power, playing tapes of Judas Priest and Roxy Music he’d made on the last tours. All fifty-two of my amps passed the tests.

We hooked it up, and the first thing I heard through it was Gerry Rafferty’s horns playing “Baker Street.” “Man, that’s clean.” Seth was impressed. “Smooth. Listen to those horns.” It was like nothing I’d heard before. They were smooth. I was thrilled.

“Who’s April Wine?” she asked. “They’ve got an album called First Glance,” I replied. People said that April Wine were the Rolling Stones of Canada, but they were unknown in the U.S.

When we pulled in, the customs officer looked in the back. The back of the wagon was filled with cases stenciled PINK FLOYD—LONDON. “Got Pink Floyd in the back of the car, do you?” he asked “Righto, mate. We shrunk ’em and stuck ’em in boxes, we did,” said Nigel.

April Wine was playing hockey rinks across eastern Canada, the only places big enough to hold the crowds.