More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

June 19 - October 22, 2023

It’s been a good trade. Creative genius never helped me make friends, and it certainly didn’t make me happy. My life today is immeasurably happier, richer, and fuller as a result of my brain’s continuing development.

Had I not been drawn out by interested grown-ups, I might well have drifted farther into the world of autism. I might have ceased to communicate.

My crazy family situation and my need to run away from home and join the working world in order to survive kept me from making that choice. So I chose Door Number One, and in doing so moved farther away from the world of machines and circuits—a comfortable world of muted colors, soft light, and mechanical perfection—and closer to the anxiety-filled, bright, and disorderly world of people.

Many descriptions of autism and Asperger’s describe people like me as “not wanting contact with others” or “preferring to play alone.” I can’t speak for other kids, but I’d like to be very clear about my own feelings: I did not ever want to be alone.

As a young adult, I was lucky to discover and join the world of musicians and soundmen and special-effects people. People in those lines of work expect to deal with eccentric people. I was smart, I was capable, and I was creative, and for them that was good enough.

In the beginning, I created circuit designs. That was something I loved to do, and did well. Ten years later, my job was managing people and projects. I enjoyed the status and respect, but I wasn’t good at management, and I didn’t like it.

“I got into this business because I wanted to be creative. I wanted to design things. Now, I’m just an administrator.”

It was time to take my chances on my own. In 1989, I quit my job and became a car dealer.

I knew fixing up cars and selling them was not creative like designing sound effects, but it had much to recommend it. There was no long commute to work. I could be myself. I would no longer live in fear for my job. There would be no one to fire me. I would no longer feel like a fraud.

The thing that saved me was my technical skill, fueled by my Aspergian need to know all about topics that grabbed my attention. And cars certainly had my attention. I may not have made money selling them, but I had the knowledge to fix them when no one else could, and people paid me for that.

I had found a niche where many of my Aspergian traits actually benefited me. My compulsion to know everything about cars made me a great service person. My precise speech gave me the ability to explain complex problems in simple terms. My directness meant that I told people what they needed to hear about their cars, which was good most of the time. And my inability to read body language or appearance meant—in an industry rife with discrimination—that I treated everyone the same.

And I loved the rugged simplicity of the Land Rover Defenders. From the first time I saw a Land Rover—in the pages of National Geographic—I had been drawn to them. One day, I told myself, I will own one of my own.

At first, I did everything—repairs, billing, scheduling, and planning. As the business grew over its first few years, I added a technician to work on cars with me, then another, and another. After almost twenty years in business, Robison Service now employs a dozen people.

When I worked as an administrator for a big company, I was in the position of bending my staff to the whims of my employer. Yet I often felt my employer’s desires and wishes were ill-conceived or just plain wrong, which made it very hard for me to feel good about imposing those wishes on others. As an owner, I imposed only my own wishes on my staff. And I only did what I believed in. I felt a lot better about that.

Standard baby drivel, I figured, especially the part about how much he looked like me. How could a six-pound baby with misshapen features and a head the size of an apple look “just like me”?

After going home that day, Cubby never returned to any hospital overnight. So, as a result of my initial marking and caution, I have a very high level of confidence that the baby that emerged from his mother seventeen years ago is the same kid living in my house today.

As we were leaving, I realized the hospital hadn’t given us very much for the $4,400 hatchery fee. No accessories. No clothes. No toys. Just the kid.

Their insistence on rolling her out made me think of an auto repair shop where the cars drive in under their own power and get towed home on wreckers a few days later. Sort of backward.

We built stuff together, too. Cubby loved Legos. But he always insisted on building the kits exactly as they told you in the instructions. Little Bear encouraged that. I couldn’t stand it. I wanted to modify them.

He wiggled his ears a little, thinking about ships. He was only five, so he almost always wanted to do anything his Dad wanted to do. It was great. I knew he’d turn on me later, but at five he liked anything I liked.

“Why is Christmas a racket?” Cubby asked.

Sitting at the table, I began scanning the book. I always read when I am eating alone, though I have learned that it’s rude to do so when eating with other people. But this moment appeared to be an exception.

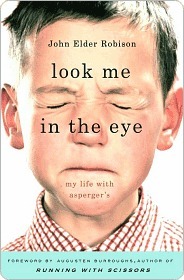

I knew that I did not look at people when I talked to them. Hell, I had been beaten up and criticized for that all through my childhood. But until I read that book I had never realized my behavior was unusual. I had never understood why people treated me the way they did. It had always seemed so mean, so unfair. It had never occurred to me that other people might find what I did (or did not do) naturally disconcerting. The answer to “Why won’t you look me in the eye, young man?” was right there in the book.

Just reading those pages was a tremendous relief. All my life, I had felt like I didn’t fit in. I had always felt like a fraud or, even worse, a sociopath waiting to be found out. But the book told a very different story. I was not a heartless killer waiting to harvest my first victim. I was normal, for what I am.

To be fair, Asperger’s syndrome was not recognized as a distinct condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the bible of mental health professionals, until fairly recently, when I was in my thirties.

At one point, I was asked to interview for an R&D job at Lucasfilm, which would have been ideal for my creative skills, but I was too afraid of going there, getting the job, and being found out as a fraud and fired once I had moved across the country. So I faded out of the music scene despite the fact that I was happier there than anywhere I have worked since.

There are plenty of people in the world whose lives are governed by rote and routine. Such people will never be happy dealing with me, because I don’t conform.

So I’m not defective. In fact, in recent years I have started to see that we Aspergians are better than normal! And now it seems as though scientists agree: Recent articles suggest that a touch of Asperger’s is an essential part of much creative genius.

I would never name a dog Kitty Kitty or Cat, and my dogs would never fall in road tar.

I had no power over the names, and I didn’t like it. Who were they, intruding into my innermost thoughts in that manner?

There can be disadvantages to my naming habits. For example, when Little Bear and I divorced and I remarried, she lost her name. She’s antagonized by being called Little Bear, because it reminds her of happier times when we were together, and I don’t have anything left to call her except “Hey!”

I was a Chicopean from Chicopee—a town famous throughout western Massachusetts as the gateway to Montague. I moved away, and like magic the club vanished from my hand and my brow straightened.

So despite my increased adaptation to polite society I still occasionally have trouble with the names I give people and things. And I’m sure many other people with Asperger’s would say their experience is similar. What is a person with Asperger’s? We are Aspergians.

When choosing a potential mate, I have always been very fearful of rejection. So I was always very careful to display little sign of interest lest the girl ridicule me. Memories of girls pointing and snickering at the few high school dances I attended are never far from my mind.

I’m actually more than reasonably happy. I’m the happiest I’ve ever been.

I attribute much of today’s sky-high divorce rate to people’s failure to choose wisely among families, and within families, among brothers or sisters. It surprises me that others don’t approach questions like this in an analytic manner, since people commonly subject car or dishwasher selections to extensive analysis, and indeed public analyses are available for many of those products in magazines. But nothing of the sort is offered for people, and when I suggest it, folks act offended. I guess that’s the directness of Asperger’s that people have trouble with.

It must be my logical consideration of a decision many see as purely intuitive or emotional that throws other people for a loop.

At the wedding, I said the first thing that came to mind, in typical Aspergian fashion: “Uncle Bob, how many times do you have to get married before you stay married?”

I really don’t know how she could possibly “always know” I could do something I never did before unless it was so trivial anyone could do it, but that’s what she says.

When Martha first met me, I was anxious and jumpy. I was always tapping my foot, rocking, or exhibiting some other behavioral aberration. Of course, now we know that’s just normal Aspergian behavior, but back then other people thought it was weird, so of course I did, too. One day, for some reason, she decided to try petting my arm, and I immediately stopped rocking and fidgeting.

Cubby likes being clean, so it’s good he didn’t know any of that. When he got bigger, he would develop the same compulsive hand-washing habit as his grandfather and his uncle, but even then he hated getting grease on his clothes or on himself. I tried to keep him out of the worst of the dirt.

As Cubby grew bigger, so did the engines. Conrail was making a change from the older General Motors locomotives with DC traction motors to the newest GE units with AC traction.

Today, I know that head bobbing and rocking back and forth and bouncing up and down—things I still do today—are characteristic of people with autism or Asperger’s. But that’s where it started, with me believing I was a steam engine, pulling those cars up the mountain. Bobbing up and down. And bouncing.

“You’re so anxious and worried! You should try antidepressants!”

And I never turned to antidepressants or liquor or pot or anything else. I just worked harder. I always figured I’d be better off solving a problem as opposed to taking medication to forget I had a problem.

Brown recluse bites are rare in New England. Of the four hundred bites logged in one database, only nine were in Massachusetts. Most were in the South. It was my father’s bad luck to be one of those nine in his weakened state.

I remembered the spring I learned to ride a two-wheel bike on the paved walkways outside the Cathedral of Learning in Pittsburgh. I never used training wheels. I went straight from a toy fire engine and a trike to a big kid’s two-wheeler, and I didn’t crash or fall off. I was really proud of myself.

My great-grandfather Dandy had asked me to take care of the farm. My grandfather Jack had asked me to take care of Carolyn and to take care of the fields and the trees his father, Dandy, had planted. Well, it’s been more than twenty years, and those things are all gone now. Carolyn died, and the house burned, and the trees and fields are all gone.

For much of her life, my mother dreamed of being a well-known author. She published a few works of poetry, but the larger work of memoir always eluded her. She had the skills and the stories, but her life got in the way. The mental illness that gave her experiences to write about also prevented her from capturing them on paper. Her stroke and partial paralysis made it hard for her to write, and hard to think. But she hasn’t given up, and I am confident that her story will appear in bookstores one day soon, alongside her postcards and poetry.

In fact, my entire life exemplifies continuing change. As a kid, I was voted “most likely to fail,” and indeed, I flunked out of high school. Yet only a few years later I became an engineer on one of the biggest rock ’n’ roll tours in the world. Then I helped design some of the first electronic games. When I was in my thirties, I made a complete change of direction, raising a kid and starting an automobile business. And at fifty, I changed course once again, becoming a successful author.