More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

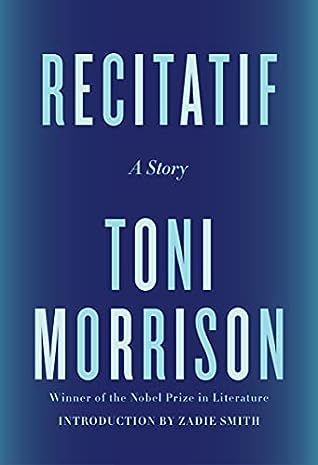

Recitatif, recitative | ˌrɛsɪtəˈtiːv | noun [mass noun] Musical declamation of the kind usual in the narrative and dialogue parts of opera and oratorio, sung in the rhythm of ordinary speech with many words on the same note: singing in recitative. The tone or rhythm peculiar to any language obs

As Twyla and Roberta discover, it’s hard to admit a shared humanity with your neighbor if they will not come with you to reexamine a shared history.

Imagine thinking of history this way! As a thing personally directed at you. As a series of events structured to make you feel one way or another, rather than the precondition of all our lives?

Difficult to “move on” from any site of suffering if that suffering goes unacknowledged and undescribed.

In the privacy of our domestic arguments we know this. We must be heard. It’s human to want to be heard. We are nobody if not heard. I suffered. They suffered. My people suffered! My people continue to suffer! Some take the narrowest possible view of this category of “my people”: they mean only their immediate family. For others, the cry widens out to encompass a city, a nation, a faith group, a perceived racial category, a diaspora. But whatever your personal allegiances, when you deliberately turn from any human suffering you make what should be a porous border between “your people” and the

...more

Like Twyla, Morrison wants us ashamed of how we treat the powerless, even if we, too, feel powerless. And one of the ethical complexities of “Recitatif” is the uncomfortable fact that even as Twyla and Roberta fight to assert their own identities—the fact they are both “somebody”—they simultaneously cast others into the role of nobodies.

Elements of this fascist playbook can be seen in the European encounter with Africa, between the West and the East, between the rich and the poor, between the Germans and the Jews, the Hutus and the Tutsis, the British and the Irish, the Serbs and the Croats. It is one of our continual human possibilities. Racism is a kind of fascism, perhaps the most pernicious and long-lasting. But it is still a man-made structure. The capacity for fascisms of one kind or another is something else we all share—you might call it our most depressing collective identity.

Fascism labors to create the category of the “nobody,” the scapegoat, the sufferer. Morrison repudiated that category as it has applied to black people over centuries, and in doing so strengthened the category of the “somebody” for all of us, whether black or white or neither. Othering whoever has othered us, in reverse, is no liberation—as cathartic as it may feel.[*13] Liberation is liberation: the recognition of somebody in everybody.

Easy, I thought. Everything is so easy for them. They think they own the world.

Two little girls who knew what nobody else in the world knew—how not to ask questions. How to believe what had to be believed. There was politeness in that reluctance and generosity as well. Is your mother sick too? No, she dances all night. Oh—and an understanding nod.

“Maybe I am different now, Twyla. But you’re not. You’re the same little state kid who kicked a poor old black lady when she was down on the ground. You kicked a black lady and you have the nerve to call me a bigot.”