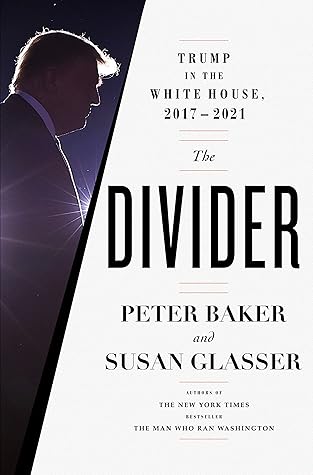

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Peter Baker

Read between

June 24 - July 12, 2023

Trump made divisiveness the calling card of his presidency.

Trump respected three types of people—those with money, those with Ivy League credentials, and those with stars on their uniform. Rich businessmen and generals were people who, in his view, had accomplished something and were worthy of admiration.

The reality was that Trump saw politics as an opportunity to make money and he had no hesitation in bending American foreign policy to his personal financial benefit.”[22]

“Bear with us.” Alluding to the famous quote often attributed to Winston Churchill, he added, “Once we have exhausted all possible alternatives, the Americans will do the right thing.”[3]

“History is clear,” Mattis told the Senate Armed Services Committee. “Nations with strong allies thrive, and those without them wither.”[8]

Selva, however, had one of those moments that were all too rare in the Trump presidency: instead of saying what Trump wanted to hear, Selva said what he thought. “I didn’t grow up in the United States, I actually grew up in Portugal,” he told the president, according to an account he later gave colleagues. “Portugal was a dictatorship—and parades were about showing the people who had the guns. And in this country, we don’t do that.” He added: “It’s not who we are.” Even after this impassioned speech, Trump still did not get it. “So, you don’t like the idea?” the president asked, incredulous.

...more

With the effort to repeal Barack Obama’s health care plan effectively dead on Capitol Hill, Trump and Republican congressional leaders turned to their other major priority—a sweeping set of tax cuts that they argued would turbocharge the economy. In the end, it would be Trump’s most important legislative achievement, but one he had very little to do with. Which may be why it passed in the first place.

“The goal is to get the president tired of fighting with you, so he’ll move on to somebody else,” the adviser explained.

Bolton had a well-deserved reputation for wanting to bomb America’s way out of almost any foreign policy problem, an aversion to international agreements, and a brash personal style as undiplomatic in its own way as Trump’s—all the makings, it seemed, of the kind of national security adviser who could easily goad the uninformed president into a war.

Pompeo had managed the dual feat of spending more face time with Trump than almost any other cabinet member while also never getting in an argument with him. The senior White House official who watched Pompeo with Trump found him to be, aside from Mike Pence, perhaps “the most sycophantic and obsequious” of Trump’s advisers.[25] He was, according to an American ambassador who worked with Pompeo during this period, “like a heat-seeking missile for Trump’s ass.”[26]

One thing Pompeo and Bolton had in common, however, was a generally hardline approach to the use of American power in the Middle East and a focus on, even obsession with, Iran. In Washington, many Democrats and foreign policy hands greeted their dual appointments as proof that Trump was headed in a militaristic direction, that this was, finally, the “War Cabinet” they had always worried about.

Where other presidents pummeled by midterm setbacks pivoted to the center to make bipartisan deals and brought in staff who could help toward that end, Trump took the opposite lesson. He wanted more power over his White House and more confrontation with his enemies. The Divider became more firmly convinced that divisiveness was the way to go.

“There were moments where you just almost had to give up,” one senior official recalled. Trump was so far gone that at times it seemed they ought to find someone to actually perform the duties of the president while the real one was busy nursing his grievances in the other room. “It was almost like we needed to give somebody a proxy,” the official added, “so that if we needed a presidential decision on something, we can still move forward.”

“He’s not on receive; he’s on transmit,” Powell told those who asked about the president.

Bolton’s time in Crazytown, at least, soon came to an end. On September 10, he finally resigned after a series of disagreements with Trump, including over the president’s insistence on hosting representatives of the Taliban at Camp David on the anniversary of September 11, when he hoped to announce his Afghan peace deal—an idea that “mortified” Joe Dunford, the outgoing Joint Chiefs chairman, and plenty of others.

Democrats were by no means sure how to proceed given this political reality, and behind the scenes there was, a senior member of the impeachment team recalled, “constant vicious infighting.” There was the obvious fault line between Schiff and Nadler, two rivals who had taken different positions on impeachment from the beginning and did not get on well personally. There was Pelosi, who was closely involved in most details. There was Douglas Letter, the House counsel, who had a seat at the table and, often, a different point of view. “Everybody was fighting with everybody,” recalled the senior

...more

Trump had sought to extort Ukraine for a personal political favor, and there was not a single Republican congressman willing to call him on it. Not one.

At most, the travel limits bought time to slow the spread of the virus to the United States, time for the government to get ready for its eventual impact—to make sure hospitals were prepared and personal protection equipment was stockpiled, to develop a robust testing system, and to undertake measures to limit transmission within the United States. But February came and went without any of that.

The emerging pandemic would expose all the weaknesses of his divisive presidency—his distrust of his own staff and the rest of the government, his intense focus on loyalty and purges, his penchant for encouraging conflict between factions within his own circle, his personal isolation, his obsessive war with the media, his refusal, or inability, to take in new information, and his indecisiveness when forced to make tough decisions.

Trump had always been indifferent to most substantive policy matters and skeptical of anything that experts, scientific or otherwise, told him. He turned everything into a political question whose answer was whatever would benefit him politically. And that is how he would approach this crisis too. “From the time this thing hit,” said an adviser who spoke frequently with the president, “his only calculus was how does it affect my re-election.”

After their last session, Christie had a moment alone with the president in the Oval Office. His final advice: “If you let him talk, he’ll hang himself. Remember what my old political science professor used to say to me: If your adversary is in the midst of committing suicide, there’s no reason to commit murder. The result is the same.”

And perhaps most pernicious of all, he would continue to tell the American people over and over again that the election was stolen by the other side even though he was the one trying to steal it.

The trick with conspiracy theories, he had demonstrated, was repetition and conviction. “You say something enough times,” he once told Chris Christie’s wife, “and it becomes true.”

Perhaps no one was more forceful in condemning Trump than Liz Cheney, who released a statement in advance of the debate echoing the comment she made on the day of the attack:

The President of the United States summoned this mob, assembled the mob, and lit the flame of this attack. Everything that followed was his doing. None of this would have happened without the President. The President could have immediately and forcefully intervened to stop the violence. He did not. There has never been a greater betrayal by a President of the United States of his office and his oath to the Constitution.[16]