More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

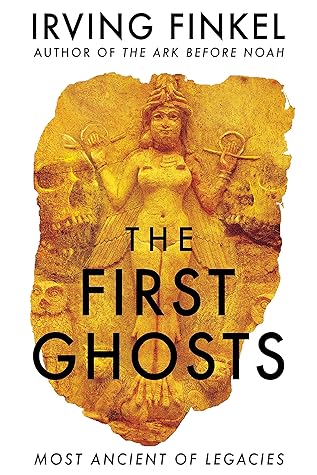

The First Ghosts: A rich history of ancient ghosts and ghost stories from the British Museum curator

Read between

August 13 - August 17, 2025

When you poke about, in fact, a surprising number of individuals will admit to ghostly experience, as long as they feel secure from ridicule.

dare say that eight out of the given twelve will, thus encouraged, come forth with something comparable that they once heard of or witnessed, never could explain, and ever after tucked away.

This book has been written to breathe life into dry bones and install Mesopotamian ghosts firmly on the historical ghost map.

quite literally, the first ghosts in human history

considering that their writing and languages have been dinosaur-extinct for over two thousand years.

Archaeologically speaking, burial as such carries no implication necessarily different from waste disposal.

are only evident after ~120,000 BP. Down to ~60,000–50,000 BP a good number of early Homo sapiens burials are known in the Middle East and Europe that, broadly speaking, pre-date the known Neanderthal burials of the same geographical areas.

when abundant flower people were alive and kicking to celebrate the news.

we are entitled to assume an underlying belief that some part of that individual was believed to be going somewhere.

pages, that long-dead Mesopotamians believed in their ghosts to the point of taking them utterly for granted.

the supposed seeing of ghosts, cohabiting with them or suffering from them, as the sort of nonsense found everywhere in gossipy or superstitious enclaves,

hardly a significant prop in bringing to life a long-vanished culture. The very op...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The cynical process of second-guessing the meaning of evidence from antiquity serves no one; my conviction is that the voices that cried out about their ghosts, argued with them and battled against them over nearly three millennia of texts in cuneiform writing must be taken at face value and hearkened to.

The important judgement is that their ghosts are not symbols or metaphors but, in their lives, realities.

We bring in Ashurbanipal, King of the World from 669 to 631 bc, to illustrate the point. Ashurbanipal: king of Assyria and the then known world; scholar, politician and warrior; the most exalted individu...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

took their bones to Assyria and prevented their ghosts from sleeping and deprived them of funerary offerings and water-pouring.

This is no fluffy, gullible, woo!-woo! ghost superstition.

The reality of the enemy ghost world is identical to his own, and his revenge perpetual.

No modern archaeologist working at Nineveh has located Ashurbanipal’s grave;

That the figure looks spectral to our eye is not coincidental: this is surely the ghost of the ravaged King of Elam come out of the darkness to taunt and haunt the hated Assyrian for evermore.

Ghosts are part of all this. It is thanks to the cuneiform writing on tablets of clay from ancient Mesopotamia that we

The Mesopotamians’ crucial words for ghost are thus the first in history; in ancient Sumerian it is gedim, in ancient Babylonian eṭemmu,

cap-à-pie.

For this book, therefore, we have direct evidence about ghosts written in the oldest intelligible writing in the world, underway before 3000 bc, extinct by the second century ad,

Huge numbers of paired Sumero–Akkadian words were systematically collected on large clay lexical tablets, the world’s first dictionaries.

Sumerian words are usually written by us in CAPITALS or plain font; Akkadian, of which there are two dialects, Assyrian and Babylonian, is written in italics.

ghosts were there from mankind’s very beginning.

Nintu was charged with recycling the body of a deliberately slaughtered god, a former rebel called We-ilu, who possessed the crucial quality of intelligence (in Akkadian ṭēmu). Later, this sacrificed god is called Alia, who had the capacity to reason. This divine flesh and blood was to be mixed with clay; the blended outcome is the human spirit (eṭemmu).

Homo sapiens mesopotamiensis primus is thus divine flesh and blood mixed with clay, animated by divine intelligence,

We (the god) + ṭēmu (intelligence) = (w)eṭemmu (spirit).

The eṭemmu is that divine element which activates the living Babylonian; what we today would call his spirit, if not his soul.

the eṭemmu endures as what we would c...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

eṭemmu or ghost.

In very special cases, immortality could be bestowed on man by the gods, but otherwise Mesopotamian persons had to die in the end

jotted down this thought-provoking Ages of Man framework on a tablet of clay: 50 short life 60 maturity 70 long life 80 old age 90 extreme old age

For any of several reasons that we shall investigate, an individual who had ‘crossed over’ and ‘gone down’ might feel compelled to return to the world from which he or she had departed.

insubstantial and flimsy, but often recognisable,

The default position was under the floor within the area of private houses,

avoided, for they would be populated by unowned and restless ghosts.

ghostly nature as a gust of wind,

ghosts were not the only such force to be reckoned with in life, for they co-existed side by side with an assortment of other, entirely non-human elements.

devils or demons;

Sumerian udug,

Akkadian utukku.

Properly speaking, of course, ghosts went down to – and were supposed to stay in – the Netherworld.

Ur by Sir Leonard Woolley

The dead in their subterranean chambers were accompanied round about by the neatly laid out bodies of their former staff, whose lives, rather shockingly, had surely, it seemed, been terminated for the purpose.

Ancient Sumerians buried their dead in the belief that they would be going on, or rather down, to the Netherworld, a world obviously in large measure comparable to that from which they had just departed.

Their dead would need material possessions.

The ‘dead-retainer’ procedure as exemplified at Ur was a surprise at its discovery and it still takes a bit of swallowing today.