More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

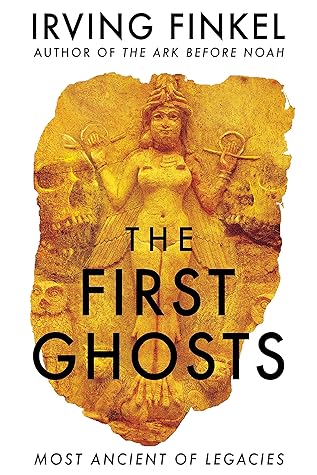

The First Ghosts: A rich history of ancient ghosts and ghost stories from the British Museum curator

Read between

August 13 - August 17, 2025

no comparable retainer graves have been found prior to those, or after those, of the Ur cemetery.

the idea seems to have started up at Ur at one point, and stopped abruptly at Ur at

another, never to resurface again in the Land-bet...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

1800 bc, although the text was likely composed for the Ur III-period court in the city of Ur in about 2050 bc. They preserve the memory of Gilgamesh’s funeral some eight hundred years earlier,

more likely, perhaps, it originated at the very demise of Gilgamesh himself.

This royal ghost, in other words, is tied at first to the body by the last breath; then is seated in the ghost-chair; then is free to go down to the Netherworld.

ultimately reflects the widespread and enduring human phobia about being buried alive,

One of the characteristic techniques in first-millennium Akkadian banishing magic is to list the types of ghosts that might be causing trouble among the populace in order to pin down the guilty party.

Sumerians under the name of Utu and by the Babylonians as Shamash, the sun god

‘the day of the lot of mankind’.

The good man,

The man who had committed some unspecified sacrilege with regard to his son.

The man who, in doing evil to his son

His name should be obliterated forever and he be a restless ghost for all time to

gruesome verdict comes the crucial list of the kinds of ghosts who also face eternal punishment.

Underpinning the system is the importance of the right behaviour between father and son,

For them, ghosts of the dead were part of life, and to set the scene we must consider the houses of the living as well as the graves

both within private houses and outside, seldom in cemeteries. What is essentially Mesopotamian from our point of view is that family dead were often laid to rest within and below the living quarters.

disconcertingly nearby and able to ‘pop up’ whenever they feel the urge is a direct consequence of two interwoven factors: burial and housing.

‘desirable family houses’,

beds are gone A Midsummer

the picture presented by their cuneiform writings is that the Mesopotamian population did more than merely believe in them. Ghosts were taken entirely for granted as part of human life within the surrounding world.

encounters did not necessarily add up to much.

At any given moment, therefore, an eṭemmu-ghost could appear to a Babylonian or Assyrian individual, busy about their daily lives, thinking about altogether different things.

There were two basic grounds for understandable restlessness in a revenant: ghost rights, disregard of which always led to unhappy or resentful ghosts, and circumstances of death, covering unwished-for or sticky endings, which always left ghosts with an unresolved problem.

In the background is one very restless and unsettled spectral personality who has been supposed to be safely down in the Netherworld.

The justice the sufferer seeks is liberation from his unwanted trouble.

thought to have been set on his victim, raising the question of who in the background was behind such villainy.

Mesopotamian terms, have been protected all along by his own personal deity.

All my flesh hurts me, the muscles of my limbs are paralysed.

ghost was set on me so as to consume me.

since the first step in driving out the victim’s ghost is to establish its identity and

for no quietus was attainable.

A ghost who has no one to call him by name 11. A forgotten ghost

Familiar ghosts were those of the family itself, in the broadest sense, including cousins, second cousins, in-laws and out-laws. It is very probable that tribal allegiance underpinned this reality on an even broader level, for the ancient Semitic population

17. A runaway ghost 18. A ghost of an evil man 19. A murderous ghost

A Babylonian scribe once reflected that the ghost is the spitting image (andunanu) of the dead person, encapsulating a deep truth.

Childbirth in antiquity was, as need hardly be stressed, hazardous, and the specialist she-demon Lamashtu, daughter of Anu (met briefly in Chapter 3), was always cruising, on the lookout for Mesopotamian women in travail or those with a new baby.

War dead meant ghosts in great number.

Dead soldiers left behind after battles, both one’s own and those of the enemy, must have always represented brewing trouble for those back home responsible for combating ghosts.

It has been suggested that the close geographical proximity of the cities at war in the third millennium indicated fear of ghosts in the covering up of heaped bodies, among other possible reasons.

ghost, an eṭemmu,

dead man, mītu,

Interestingly, Mesopotamian ghosts are perfectly visible in a daylight hour sighting as well as in the – to us conventional – dead of night.

The phrase ‘like a living one’ probably means the spectre must be clothed, and so, for a minute, could be thought to be a living – but unfamiliar – person.

Undeniably, a sighting did not usually add up to good news.

It would be a grave misjudgement to take these faraway Mesopotamian scenarios as comparable in this way, implying an unswerving, backdated historical rule that ghosts mean bad news.

There is no flirting here with spine-chilling, ineluctable Hollywood fate; this is a practical handbook to deal with a real and common problem among human beings.

day of the month. If we are instructed that a person who starts tomb-construction on the fifteenth of any month of the year will not only become ill with dropsy but, in the end, will not even get buried themselves, it is a fairly safe bet that no one ever did start such a construction.

these one-line omens not so much as fixed cause-and-effect rulings, but as a set of warnings.