More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Russ Ramsey

Read between

June 2 - June 30, 2023

It is hard to render an honest self-portrait if we want to conceal what is unattractive and hide what’s broken. We want to appear beautiful. But when we do this, we hide what needs redemption—what we trust Christ to redeem. And everything redeemed by Christ becomes beautiful.

This is how we should see others and how we should be willing to be seen by others: broken and of incalculable worth.

Good and evil point to the reality of undefiled holiness. Honesty and falsehood point to the existence of absolute truth. Beauty and the grotesque whisper to our souls that there is such a thing as glory. Goodness, truth, and beauty were established for us by the God who is defined by all three.

The pursuit of goodness, the pursuit of truth, and the pursuit of beauty are, in fact, foundational to the health of any community.

Goodness was a foundational part of our intended design from the beginning. To live according to the goodness inherent in our creation is a matter of both character and function; we’re called to be good and to do good.

we see in Genesis that creativity is bound up in the act of work itself. Adam’s creative work was a beautifying work.

When we set out to make something beautiful, we’re drawing from that ancient instinct—however corrupted it may be from the fall—to care for and beautify Eden.

many Christians in the West tend to pursue truth and goodness with the strongest intentionality, while beauty remains a distant third. Yet when we neglect beauty, we neglect one of the primary qualities of God.

The pursuit of beauty requires the application of goodness and truth for the benefit of others. Beauty is what we make of goodness and truth.

Beauty draws us deeper into community. We ache to share the experience of beauty with other people, to look at someone near us and say, “Do you hear that? Do you see that? How beautiful!”

That beauty, and the ache that comes with it, is a powerful, necessary, shaping force for any who would desire to know God.

God’s creation is inherently beautiful. There is beauty all around us, and it points to the glory of God.21 When God rested from creating, he said the world he made was “very good.”22 This goodness is not according to the world’s standards, but to God’s. And in God’s kindness, the fall did not erase the beauty of creation. It’s there to behold, if we’ll only look. And when we see it, it will teach us about the Author of beauty.

We should engage with beauty deliberately and regularly because these are the clothes we will walk around in for all eternity.

Without beauty, truth and goodness lie flat, and they were not meant to. They were meant to be adorned. They were meant to be attractive.

When we create, we reflect the image of the Creator. There is a cycle of creation here: Beauty inspires creativity, and creativity is a path to more beauty.

Creation testifies to a Maker who delights in beauty for beauty’s sake.

So many things in our world are beautiful but didn’t need to be. God chose to make them that way so he might arrest his people by their senses to awaken us from the slumbering economy of pragmatism. That awakening is a vital function of beauty. This is the gift of beauty from an artist to their community—to awaken our senses to the world as God made it and to awaken our senses to God himself.

Each story is different. Some conclude with resounding triumph, while others land with the thud of despair. But all of them raise important questions about humanity’s hunger and capacity for glory, and all of them teach us to see and love beauty.

Beauty is a relic of Eden—a remnant of what is good. It comes from a deeper realm. It trickles into our lives as water from a crack in a dam, and what lies on the other side of that dam fills us with wonder and fear. Glory lies on the other side. And we were made for glory.

His lifestyle afforded him the opportunity to indulge any appetite he wanted—which he did—and his orthodoxy fought to bind his conscience to the love and law of the Savior he believed held his soul fast.

Living with limits is one of the ways we enter into beauty we would not have otherwise seen, good work we would not have chosen, and relationships we would not have treasured. For the Christian, accepting our limits is one of the ways we are shaped to fit together as living stones into the body of Christ. As much as our strengths are a gift to the church, so are our limitations.

The same time and pressure that gave us the stone from which David was cut could reclaim him at any moment.

Our best attempts at achieving perfection this side of glory come from an innate awareness that it not only exists, but that we were made for it.

We who bear the image of God have taken this man of stone and given him a dusting of flesh. How much more will we, who are bound for glory, shed the limits and imperfections of these perishable frames for bodies that will forever bear up under the eternal weight of glory?

Art was a form of evangelism—a pictorial welcome into the faith with the goal of inspiring devotion to God and the church.

As viewers developed their visual vocabulary, they could stand in front of a painting and read an entire sermon in a single frame.

He didn’t want to make art that was only meant to be glanced at. He wanted to create a visceral experience for his viewers—something that would stop them, trouble them, or arouse whatever might be sleeping in their souls.

He was a painter for the poor, whose mission was to emphasize that the gospel was for poor people.

Caravaggio gravitated toward situations where the sacred confronted the profane, and he was moved by the power of Christ to change people’s heart.

In a single frame, Caravaggio depicts mercy as a costly endeavor, something that cannot be done without fully entering into the misery and need of another.

When he was in the throes of despair, desperate, and afraid for his life, he created these two works that tell the story of the birth of the tender Savior who grew into a man who wept over suffering, sickness, and loss while demonstrating his power over death itself. This is the paradox of Caravaggio—he brought so much suffering on himself, with such bravado and acrimony, yet when he picked up his brush, the Christ he rendered was the Redeemer of the vulnerable.

Based on the content of his art, along with the biblical truth that God’s mercy is a product of his love and not our conduct,54 we cannot dismiss Caravaggio from the kingdom of God. We cannot conclude that his behavior was so destructive that it shattered the grace of the Lord he painted with such reverence.

The pattern in Scripture is that of God working through unlikely servants for the glory of his name and the spread of the gospel.

Caravaggio lived a destructive life. But his art shouts into that chaos that just as Christ could call the tax collector to follow him or draw from the recesses of the hardest heart the beauty and wonder that poured out of Caravaggio between his seasons of Carnival, our Lord’s capacity to extend grace is greater still. And grace transforms even the hardest hearts.

He wanted to draw us in, capture our imaginations, instruct us on how we should relate to what was happening on the canvas, and bear witness to what he believed to be true about the world he painted and his place in it.

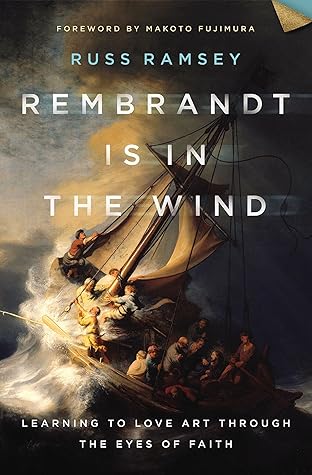

By painting himself into the boat in The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, Rembrandt wants us to know that he believes his life will either be lost in a sea of chaos or preserved by the Son of God.

Isabella Stewart Gardner walked in the way of the widow from Nain and had carried her sorrows to this place in the hope of finding some rest. When she lost her baby in a sea of grief, she turned to beauty for healing. When she lost her husband, she determined to create something that would not die—a museum that would live forever. And she would give it to the world.

Isabella was one person in a long line of many who have, in their own way, tried to arrest the decay of a dying creation. She wanted to give us something beautiful, something lasting, something whole born out of a groaning too deep for words.25 It was a defiant act of war against death, using beauty as her weapon.

This is a hard world, where children die and widows grieve. This is the nature of the storm we are all painted into. The same sea that lures us in with its beauty and bounty surges with a power that can destroy us without warning. And eventually there comes a reckoning. Rembrandt knew this well. So did Isabella Stewart Gardner. So did every man in the boat.

Things will not always be this way. Sad things such as these will one day come untrue.

The disciple’s question reverberates down through the ages—does God care about our perishing? Jesus came treading on our roughest seas, speaking peace into the gale. And he will do it again. His triumph over the grave calls those who are perishing to be born again into a new and living hope. The peace he has brought by his resurrection is neither myth nor fantasy. It is an inheritance that will never perish, kept for those who believe, world without end.

So we learn to hope in a coming kingdom. But we do so, knowing that in this one, at least for now, Rembrandt is in the wind.

We reflect God in ways no other created thing does. And our call as human beings reflecting a Creator is to imitate him, not only in his moral ethic but also in his creative work. We were created to create. When human beings do the work of creation—bringing something into being that did not previously exist—we reflect that part of God as Creator.

We are created to make things, so we do. But we never truly work alone.

So many things were designed and fashioned in order for the artist to sit down and do their work—even their chair and the floor on which it rested. And so many people contributed their skills: carpenters, weavers, potters, metalsmiths, brush makers, architects, distillers, and even lens makers. When we stand before a Vermeer, we are seeing not only his work, but also the work of all these others and many more. Everything we make, in some measure, relies on the help of others. All of us rely on borrowed light. Even the blind composer sits at a piano not made in darkness.

By light we do our work. By that same light others behold it. And all of the light is borrowed from God.

We live in communities that need goodness, truth, and beauty. And we play a role in advancing those transcendentals that make us human.

This is the mysterious, transcendent quality of art—something in the liniment oil and pigment breaks through the plain of the canvas and penetrates the human soul in a way that suddenly and inexplicably matters.

This was what Vincent wanted to create—art that would transfer from his easel into someone else’s soul to work as a balm of healing for the broken.

Somewhere in that flurry of motion between painter and canvas was a man held captive by an insatiable appetite to capture the world he wanted while being unable to connect with the world he had.