More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Russ Ramsey

Read between

March 25 - March 29, 2025

Lilias Trotter, whose missionary gaze into the beautiful—not just her art but the art of her life—revealed astounding insight from the simple sight of a bee: “He was hovering above some blackberry sprays just touching flowers here and there, yet all unconsciously life, life, life was left behind at every touch.”

This is how God sees his people. We are fully exposed in our shortcomings, yet we are of unimaginable value to him. This is how we should see others and how we should be willing to be seen by others: broken and of incalculable worth.

Beauty is a relic of Eden—a remnant of what is good. It comes from a deeper realm.

Our best attempts at achieving perfection this side of glory come from an innate awareness that it not only exists, but that we were made for it.

He didn’t like the idealized image of humanity and much preferred to paint people as they were, with their flaws and defects on display. He was a painter for the poor, whose mission was to emphasize that the gospel was for poor people. He wanted to leave room for ambiguity, doubt, and sorrow. He wanted the simple difficulty of living in this world to be written on his subjects’ faces.

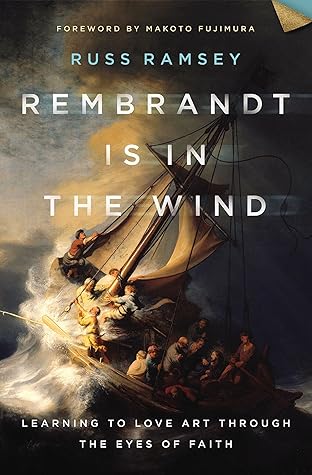

Life etches itself onto our faces as we grow older, showing our violence, excesses or kindnesses. Rembrandt van Rijn

We reflect God in ways no other created thing does. And our call as human beings reflecting a Creator is to imitate him, not only in his moral ethic but also in his creative work. We were created to create. When human beings do the work of creation—bringing something into being that did not previously exist—we reflect that part of God as Creator.

We are created to make things, so we do. But we never truly work alone.

It was imperative for these artists to work in community, not in isolation. They needed one another. They needed to be around each other. They needed to be able to share a common space—a place where they could gather and speak freely. A place where they could show what they were working on to get feedback, encouragement, and pushback. They needed voices that understood what they were trying to do. They needed assurance that they were not fools. And if they were in fact fools, they needed to be a tribe of fools together. They needed a place, and that’s exactly what Bazille gave them.

The Impressionists were an early version of indie artists—ditching the major labels, working their own merch tables, and trusting that together they could hold one another up and break through to earning something resembling a livable wage. They took this seriously. If they were going to make it, there was work to be done.

Here is where community is so vitally important. Without it, we might be tempted to believe that the limitations and hardships we experience are unique to us and are therefore ours alone to navigate. That just isn’t the case. Being part of a community puts us in proximity to other strugglers—people who can reassure us that we are not alone, who can offer wisdom because they’re familiar with the woods we’re lost in, and who can benefit from the experiences and insights we’ve gained through the hardships we’ve endured.

Quoting the nineteenth-century priest Ugo Bassi, Lilias wrote in her diary, “Measure thy life by loss, not by gain; not by the wine drunk, but by the wine poured forth. For love’s strength standeth in love’s sacrifice, and he who suffers most has most to give.”32

Learn to contribute beauty to this world—modest though your part may be. It’s okay to be a slow learner.

What are you mastering? What are you practicing in order to make clear what you don’t yet know? If you’re anything like me, I’m sure you reach points where you begin to wonder if it might just be easier to plateau. And if not plateau, then quit altogether. Don’t. Please. This world is short on masters, and consequently, it’s a world short on joy too.