More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

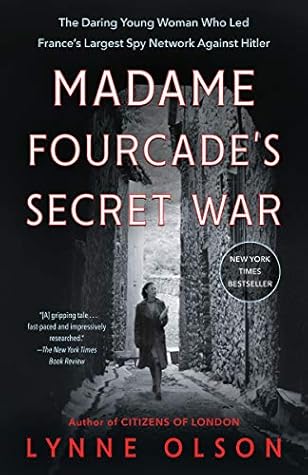

Lynne Olson

Read between

July 27 - August 12, 2020

demure

the comparative handful of French men and women who rose up in 1940 to defy the Nazis.

Over the course of the conflict, Fourcade, the only woman to head a major resistance network in France, commanded some three thousand agents,

and France’s most celebrated child actor. Thanks to Marie-Madeleine’s determined efforts, almost twenty percent were women—the

Hedgehog.

“resisters shared one characteristic besides bravery: contrariness. They were disputatious, argumentative, non-conformist, did not enjoy being ordered about.”

Although there have been floods of books and films about the French resistance, little has appeared about her and her network—or, for that matter, about any other intelligence organization.

In the late 1960s, Marie-Madeleine Fourcade pulled back the veil cloaking her wartime activities in her gripping memoir, Noah’s Ark,

“To this day historians of the Resistance persist in the belief that no women led Resistance networks, blatantly ignoring the work of Marie-Madeleine Fourcade,” the British historian J. E. Smyth noted in 2014.

“The minds of the French generals had ground to a halt and were already thickly coated with rust.”

They also went out of their way to block the advancement of younger, more vigorous officers who preached the need for a revolution in military tactics and strategy.

three decades of the twentieth century, Shanghai was considered the essence of exoticism, mystery, and excitement. As an open city, it required neither a visa nor passport to enter, providing a haven for an extraordinarily eclectic array of immigrants, among them White Russians fleeing from the Bolsheviks; Chinese warlords and revolutionaries; American and European gangsters and spies; drug smugglers; and international arms dealers.

As cosmopolitan as Shanghai was, the British dominated the city economically and politically and set the tone for the foreign community.

“tagines

A year after their wedding, Marie-Madeleine gave birth to a son, named Christian.

scion

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry,

Marie-Madeleine also took flying lessons and acquired a pilot’s license.

She worked at Radio-Cité, the country’s first commercial radio station, initially in its advertising department and then as a producer of entertainment programs, partnering with the writer Colette on a

half-hour series f...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

singers like Édith Piaf and Maurice Chevalier and offering France’s first radio news programs.

France had long been known for what one historian called its “people’s ineradicable love of political squabbles,”

more than forty governments had come and gone—an average of one every six months.

financial scandals in the 1930s involving bribes paid to ministers and parliamentary deputies by businessmen and bankers seeking favorable government treatment.

The French Communist Party, which dominated much of the country’s labor movement, was responsible for fomenting a massive wave of wildcat strikes across the country that caused significant disruption to factory production.

As the country teetered on the brink of anarchy, the last thing its people and government wanted was to confront the looming threat of another war with Germany.

Most French citizens, for all their corrosive divisions, were united in the belief that France must never fight another such war again.

That belief had some evidence to support it. Since the 1920s, the Soviets had secretly provided Germany with facilities deep within their country for the making and testing of tanks, aircraft, and poison gas and for the training of Luftwaffe pilots and Wehrmacht troops—all activities that had been prohibited by the Versailles Treaty.

was a particular target of Communist subversion, which included an intensive propaganda campaign by the French Communist Party aimed at demoralizing French troops and sowing defeatism within their ranks.

he created a secret organization of army officers, called the Corvignolles,

Throughout 1939 and into 1940, Navarre and other French intelligence officers passed on reports to top government and military leaders of German plans for an invasion of France through the Ardennes. Both leadership groups rejected the intelligence, preferring to believe that any future German offensive would come through the flatlands of central Belgium,

Finally, Marie-Madeleine and her party reached Berry, a rural region in the Loire Valley, where she hoped to stay with a close friend, Aurore Sand—the granddaughter of the famed novelist George Sand.

Château de Nohant,

It was here, she knew, that Chopin had composed some of his masterpieces, including the Polonaise in A-flat Major, the Sonata Funèbre, two nocturnes, and four mazurkas.

Étude op. 10, no. 12,

In a broadcast to his countrymen, the eighty-four-year-old Pétain attributed France’s defeat to “too few arms, too few allies,” and the country’s own moral failures, which included a lack of discipline and an unfortunate “spirit of pleasure.” At the same time, he expressed his compassion and concern for the millions of refugees still choking France’s roads and appealed to them and their compatriots to “rally to the government over which I preside during this difficult ordeal.” As shocked as she was by Pétain’s capitulation, Fourcade was even more stunned by the joyful reaction of the people

As Fourcade saw it, the French, in their understandable relief that the war had ended for them, failed to recognize that in the process, they and their country had lost their souls.

He was the only French official willing to abandon his homeland to continue the fight against Hitler.

There were endless queues in front of Vichy’s most fashionable restaurants, with the competition for tables particularly fierce at the dining room of the Hotel du Parc, where Pétain and leading members of the government held court.

to Pierre Laval, Pétain’s deputy and the power behind the throne.

From its beginning, the Vichy government instituted policies of persecution and repression of French citizens, particularly Jews. In early July 1940, less than a month after France’s capitulation, Vichy began enforcing anti-Semitic measures in its territory without receiving orders from Berlin to do so.

Even before Pétain, France had treated women as second-class citizens, refusing them the right to vote, to own or control property without permission from male relatives, or to have a bank account in their own name.

To her, Vichy was nothing but a nest of gossip, infighting, and intrigue, filled, as she put it, with the “aristocracy of defeat”—politicians, businessmen, civil servants, military officers, and others—all seeking jobs or other personal or political gain from the new government.

The conspiratorial Navarre managed to convince Pétain that he had given up his rebellious ways and now fully supported his former boss’s policies.

With Pétain’s blessing and Vichy funds, Navarre and Fourcade leased one of the few hotels not appropriated for government offices and hired a small staff to run it, with Fourcade as its manager.

hackneyed

In reality, Vichy was far from being a monolithic regime.

The most notable anti-German rebel was General Gabriel Cochet, a senior officer in the French air force and a former head of the Deuxième Bureau.

Colonel Louis Baril, had sent a message of support and solidarity to MI6 shortly after the armistice.

none was as crucial as a secret codebreaking operation at a secluded château in the countryside of Provence. Its head was Captain Gustave Bertrand, the director of the Deuxième Bureau’s radio and cryptography department.