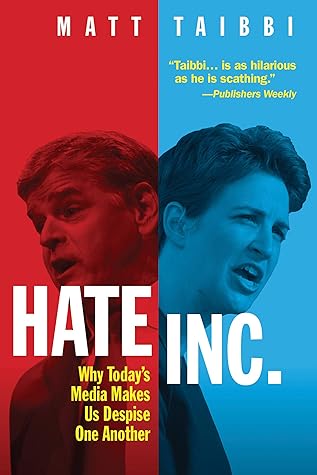

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Matt Taibbi

Read between

March 18 - April 6, 2022

When Trump won, the distinctions between these outlets vanished almost overnight. Content increasingly was organized around furious opposition to Trump. The theme of unending crisis—not just crisis but emergency, a distinction expressed by news agencies via blaring chyrons screaming descriptors like BREAKING—was central to the new coverage concept.

Blue-state audiences had to be trained to think this way. Coverage of Trump was so constant and full-throated that all other topics stopped having news value. The first stories to be memory-holed were the ones that preceded Trump’s entrance into politics: war crimes in Iraq, drone killings, financial inequality (destined to be re-christened a mockable fictional problem called “economic insecurity”), the failure to close Guantanamo Bay, lack of enforcement of white-collar crime, and a dozen other things.

It was therefore stunning to watch the universal lack of insight when the anti-candidate who rampaged through our idiotic campaign carnival in 2016 was not only a reality star, but also a beauty contest aficionado. Trump was a demon from hell sent to punish all of these reporting sins.

“The problem with false balance doctrine is that it masquerades as rational thinking,“ she said, adding: “What the critics really want is for journalists to apply their own moral and ideological judgments to the candidates.”

Rutenberg argued we should re-imagine “objectivity” in a way that would “stand up to history’s judgment.” This was basically code for accepting the argument about making political judgments about impact before running stories, even newsworthy ones.

Spayd pushed back when Carlson called this “advocacy,” and said it was something more subtle and maybe worse: an “unrecognized point of view that comes from… being in New York in a certain circle, and seeing the world in a certain way.”

But the fact that “objectivity” was less about principle than profit, stylistically silly, and easily manipulated into masking all sorts of awful political realities (historically, from racism to American military atrocities abroad), didn’t mean it was worthless. “Objectivity,” above all, was great protection for reporters. Having no obvious political bent was a prerequisite for taking on politicians.

This is more or less where we are now, and nobody seems to think this is bad or dysfunctional. This is despite the fact that in this format (especially given the individuated distribution mechanisms of the Internet, like the Facebook news feed) the average person will no longer even see—ever—derogatory reporting about his or her own “side.” Being out of touch with what the other side is thinking is now no longer seen as a fault. It’s a requirement, because:

Sometime in the spring or summer of 2016 I started to notice blowback every time I mentioned the economy in connection with Trump voters. Very quickly (it’s amazing how fast these trends gain traction in the social media age) the use of the term “economic insecurity” became a meme-worthy offense on social media.

couldn’t bring himself to denounce open racists and said instead that “both sides” were at fault, the terms “white supremacist” and “white nationalist” became common to describe Trump’s tenure.

But his voters? Did it really make sense to caricaturize sixty million people as racist, white nationalist traitor-Nazis?

Before you can argue the justice of this point, realize what it means. If we’re now saying all Trump supporters are mainly bent on upholding the supremacy of white, Christian, heterosexuals, that’s miles beyond even Hillary Clinton’s take of just half of Trump supporters being unredeemable scum. It’s a sweeping, debate-ending dictum. There is us and them, and they are Hitler.

But racism as the sole explanation for Trump’s rise was suspicious for a few reasons. Chief of which being that it completely absolved either political party (both the Republican and Democratic party establishments were rejected in 2016, in some cases for overlapping reasons) of having helped create the preconditions for Trump.

The Trump phenomenon was also about a political and media taboo: class. When the liberal arts grads who mostly populate the media think about class, we tend to think in terms of the heroic worker, or whatever Marx-inspired cliché they taught us in college.

Because of this, most pundits scoff at class, because when they look at Trump crowds, they don’t see Norma Rae or Matewan. Instead, they see Married with Children, a bunch of tacky mall-goers who gobble up crap movies and, incidentally, hate the noble political press. Our take on Trump voters was closer to Orwell than Marx: “In reality very little was known about the proles. It was not necessary to know much.”

Non-voters are the single biggest factor in American political life, and their swelling numbers are, just like the Trump phenomenon, a profound indictment of our system. But they don’t exist on TV, because they suspend our disbelief in the Hitler vs. Hitler show.

But the core dynamic of his job was not much different from what most of us do. We’re mainly in the business of stroking audiences. We want them coming back. Anger is part of the rhetorical promise, but so are feelings of righteousness and superiority.

As far back as 1984, the Republican Party was urging people to vote Reagan because Walter Mondale was a “born loser.” On the flip side, the name “George McGovern” became so synonymous with “loser” that it birthed an entirely new brand of “Third Way” politics, invented by the Democratic Leadership Council and people like Chuck Robb, Al From, Sam Nunn, and Bill Clinton. The chief principle of this new politics was that it had a chance of winning.

We can’t get you there unless you follow all the rules. Accept a binary world and pick a side. Embrace the reality of being surrounded by evil stupidity. Feel indignant, righteous, and smart. Hate losers, love winners. Don’t challenge yourself. And during the commercials, do some shopping. Congratulations, you’re the perfect news consumer.

One development was that a less overtly nasty version of The Peasants Are Revolting called “media illiteracy” began to be bandied about in academic and press-crit circles. Under this theory, hatred of the media arose out of the “confusion” of the digital age, in which people (read: dumb conservatives) had a hard time determining the validity of sources.

The whole “electability” question usually implies a) there’s a candidate in this field who’s most likely to win, and b) there’s a candidate who appeals to you on a policy level, and c) those candidates are not the same person. To this day people believe this is the case. Generations of voters have been trained to consider the politician who represents their views as unlikely to be “electable.” Most people are terrified of throwing their vote away, so they’ll steer clear of any candidate the press tells them has no chance. Particularly when the incumbent is odious, voters won’t vote their own

...more

It goes without saying that language about “firewalls” is crazy and insulting. It implies the nomination is the property of the presumptive frontrunner, and challengers are destructive forces. In this case it was openly argued before the primary in California (where fires are sort of an issue) that Clinton’s best hope was the historical Latino distrust of black candidates.

Politics, despite the fact that it talks about itself as baseball all the time (“inside baseball” is the favored term of people who think they’re playing it), is not baseball. In baseball, batters don’t intentionally strike out because they’re told the pitcher has high strikeout rates.

The easiest way to predict what kinds of “electability” stories you’ll see in an election season is to look at the field of candidates and see which ones have a lot of lobbying and ad money behind them. Those candidates will be described as electable. Everyone else will get the “polls say” treatment. Be wary of our version of junk science.

The authors of The Party Decides let us in on a secret: the McGovern-Fraser commission didn’t actually disenfranchise party bosses and donors! Actually they still control things a lot! The “invisible primary,” they argued, was and is a pre-primary period in which party bosses “scrutinize and winnow the field before voters get involved, attempt to build coalitions behind a single preferred candidate, and sway voters to ratify their choice.”

These are descriptors invented for people who insist on voting for the candidate of their choice, like for instance an antiwar voter who won’t vote for a pro-war candidate. Snobs! In the politics-as-eating metaphor, a purist is just an annoying customer who won’t just eat what’s served.

Reporters tend to describe the winner of the “invisible primary” as more electable and the wiser choice. In some places you will see voters who reject the party-approved candidate described as “off the reservation” or “stubborn.”

THE NEWS IS A CONSUMER PRODUCT If you take away nothing else from this book, please try to remember this.

You get the same rush from pulling the dense metal phone out of your jeans that a smoker gets withdrawing a softened cardboard Marlboro box. My phone cover has a waffle-patterned back to it. If I close my eyes, I know exactly how it feels. Close your eyes and try it. You can probably do the same thing. Before they target your lungs, cigarettes win you over with smell and touch and sound: that coffee-like aroma, the brittle feel of the rolling paper, the whooshing noise of a spark becoming a flame.

Internet-fueled addiction is frankly just a new quirk to the crass consumer experience that is (and has been for some time) the news. The notion that you are reading the truth, and not consuming a product, is the first deception of commercial media. It’s the same with conservative or liberal brands. In both cases, the product is an attention-grabber, a mental stimulant.

In fact, the tension between the sheer quantity of horrifying news and your real-world impotence to do much about it is part of our consumer strategy. We create the illusion that being informed is a kind of action in itself. So to wash that guilt out—to eliminate the shame and discomfort you feel over doing nothing as the world goes mad—you’ll keep tuning in. The “You don’t actually need to be watching this all day” rule would be true even if news stories were sorted logically and according to social importance. They aren’t: WE ARE NOT INFORMING YOU. WE CAN’T, ACTUALLY

American Psycho was a book about how the American idea of personality is constructed around things we buy. We may be insane monsters inside, but we work hard to have good consumer taste on the surface. Ellis understood that most of us, when we read the news, are really just telling ourselves a story about who we like to think we are, when we look in the mirror. The main difference between Fox and MSNBC is their audiences are choosing different personal mythologies. Again: this is a consumer choice. It’s not the truth, but a truth product.

The reason? Images of poor, inarticulate people are disturbing to audiences, especially upscale ones (read: people with disposable incomes who can respond to advertising). That’s why we don’t show poverty on TV unless we’re laughing at it (Honey Boo Boo) or chasing it in squad cars (Cops).

I’ve run into trouble with friends for suggesting Fox is not a pack of lies. Sure, the network has an iffy relationship with the truth, but much of its content is factually correct. It’s just highly, highly selective—and predictable with respect to which facts it chooses to present.

In that orgiastic case we dropped a twenty-one thousand-pound bomb, which initial reports said killed thirty-six “militants,” and “no civilians were affected by the explosion.” By the next day, April 15, 2017, the death toll was “at least 90 militants,” and none of them were civilians! How about that for precision! America, fuck yeah!

If a candidate had to fib or back off a campaign promise, the new generation of scribes explained a politician’s job was to accept the “burden of morally ambiguous compromise.”

By the mid-2000s, journalists at the top national papers almost all belonged to the same general cultural profile: liberal arts grads from top schools who lived in a few big cities on the east and west coasts. This was less true of reporters at more regional newspapers, who very often were more adversarial and took on local industries and politicians with more gusto than their national counterparts.

What’s the Matter With Kansas? was a prescient portrait of a Democratic Party that was transforming into what Frank would later term a “party of the professional class”—urban, obsessed with its own smartness, worshipful of meritocracy and credentialing, and exquisitely vulnerable to accusations of elitism.

If Democrats could hear hard truths like the ones in What’s the Matter With Kansas? they were in good intellectual health. Years later, it looks like some of that was a mirage. Frank today suspects the more difficult parts of What’s the Matter With Kansas? were just overlooked.

Trump’s speech is almost word for word a recitation of the talking points Frank had warned in What’s the Matter With Kansas? were in danger of being lost forever to the Democratic Party. The New York billionaire is, of all things, appropriating the language of the original Populist movement.

Contrary to what was reported, Trump speeches tended to be policy-based and often as much about class as race or nationality.

In the summer of 2016, hundreds of reporters descended into the hollowed out ex-industrial towns where Trump was finding success, ostensibly to answer that question. These places were often in a state of near-devastation, overrun with unemployment, debt, an opiate crisis, and, unique in industrialized countries, declining rates of life expectancy. People in these places were pissed, and had been for a while. But newspapers rarely commented on this. By the summer of 2016, Trumpism became very nearly synonymous with terrorism, i.e. something whose origins you didn’t need to ask about if you were

...more

Apparently Hillary Clinton wasn’t trying. So, no big deal. That Trump would later be ridiculed for his delusions about crowd size was beyond ironic, considering how much time those same press critics spent explaining away the enthusiasm gap in 2015–2016.

The tough-talking, bard-of-the-streets, people’s columnist of the Royko or Jimmy Breslin school once held exalted positions in most big cities. These larger-than-life figures had begun to vanish from American newspapers in the eighties and nineties. They were replaced, en masse, by representatives of what Frank calls “Ivy League monoculture,” pundits like Boot and David Brooks and E. J. Dionne and Ross Douthat, whose ideas about politics were tied up more with modernity than class. These were voices for the yuppie set, urban, educated, white collar, in perpetual awe of productivity and

...more

columnist job in the hometown paper was almost always a white guy, and it was a great thing when the business at least began to diversify. But in fixing one problem, another was created. The blue-collar voices lost were not replaced.

Frank represented a link to that vanishing tradition because he at least tried to search out the perspective of working-class voters. He was celebrated for this in the Bush years, when his work could be offered by upscale Democrats as evidence regular people were being conned by Reaganites into “voting against their interests.”

A University of California professor named Joan Williams went through something similar. She came from a family with working-class origins and felt she had some insight into Trump’s base, in particular via memories of her father-in-law who hated professionals but admired entrepreneurs.

For many blue-collar men, all they’re asking for is basic human dignity (male varietal). Trump promises to deliver it. The Democrats’ solution? Last week the New York Times published an article advising men with high-school educations to take pink-collar jobs. Talk about insensitivity.

She says the “intelligentsia of the professional managerial elite” seems remarkably blind to the fact that working-class Americans are paying attention to how our political and financial pie is being divvied up. They know, she says, that “opportunity has been incredibly more concentrated in a small dense metropolitan area,” and they’re angry about it.

Academics like Williams have fewer places to get the word out, among other things because there’s no longer much space for alternative viewpoints of any kind. The 2016 race coincided with another mass die-off, the Ice Age of newspapers in general. “By now, there are only two newspapers left, the New York Times and the Washington Post,” Frank says. “And they’re identical. They say the same things. It’s an incredibly limited ecosystem.”