More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

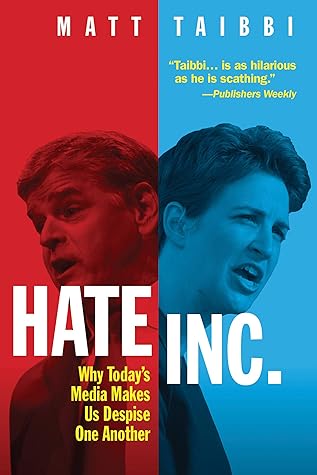

by

Matt Taibbi

Read between

March 18 - April 6, 2022

The sheer number of articles wondering if Trump’s win suggests there’s “too much democracy” these days conveys more about who is doing the analysis than it does about the political situation.

Politicians and journalists alike have absolved themselves of any responsibility for what’s gone wrong, settling instead for endless finger-pointing at people who are irredeemably stupid and racist—who just “have bad souls,” as Frank puts it. This convenient catchall explanation makes the op-ed page the place where upscale readers go to be reassured they never have to change or examine past policy mistakes, even if it means continuing to lose elections.

Who needs to win elections when you can personally reestablish the rightful social order every day on Twitter and Facebook? When you can scold, and scold, and scold, and scold. That’s their future, and it’s a satisfying one: a finger wagging in some vulgar proletarian’s face, forever.

The media was supposed to help society self-correct by shining a light on the myopia that led to all of this. But reporters had spent so long trying to buddy up to politicians that by 2016, they were all in the tent together, equally blind. Which is why it won’t be a shock if they repeat the error. You can’t fix what you can’t see.

We’re also training audiences to fear being caught not knowing, and to believe it’s shameful to be ignorant of news. You think Wolf Blitzer doesn’t know what’s going on in the Sri Lankan civil war? Who’s the reigning party in Japan’s House of Councilors? Who’s currently occupying Idlib?

News companies don’t just want you feeling ashamed of not knowing the news. That’s desperate marketing, ring-around-the-collar tactics. They want you so emotionally invested that your psyche falls apart if the wrong story appears on screen. We want you awake at night, teeth chattering, panicking about things over which you have no control.

News purveyors knew: if they could find a way to cover politics like sports, and get news consumers behaving like the emotional captives we call sports fans, cash would flow like a river. How to pull that off? The main thing is, don’t break the spell.

In fact, the two most taboo lines in all media in America are I don’t know and I don’t care. The dynamic is more grotesque and ridiculous in sports, as one radio man found out in early 2019.

Most sports media trains audiences to see the world as a weird dualistic theology. The home city is a safe space where the righteous team is cheered and irrational worship is encouraged. Everywhere else is darkness. Opposing fans are deluded haters. Increasingly most local fan bases are encouraged to see the national sports media as arrayed against them, too.

“Definitely,” he says. “Since Trump’s been President… It’s just like sports. You pick a side and that’s your identity. There’s a lack of nuance. A lack of gray area.”

But stations still usually make sure there’s no off-the-reservation opinion on the horizon. If you’re brought on to play the Democrat, they make sure in advance you’ll stay in that lane. If you’re brought on to argue the red side, same thing.

the first rule of Fight Club is no talking about Fight Club, the first rule of political debate shows is no reminding audiences they’re watching political debate shows.

Nobody on any channel ever tells you to take a deep breath and relax. On the contrary, the whole aesthetic of modern news is to make you feel a constantly rising tension, a fear you’re missing out.

The deceptions lay in the notion that there’s anything the ordinary person can do about the reams of troubling information we throw at you.

Yet we bombard you with headlines all day long, and increasingly present the news as a sports-like zero-sum battle between two sides, in which every day can only end with heartbreak or triumph for your belief system. In sports it’s a major taboo for a broadcaster to admit that the outcome of any sporting event shouldn’t be in the top 50 concerns for any sane human being, or point out that just because teams from two cities are playing each other, doesn’t mean people from those places should dislike one another.

We get people so invested in news stories that they’re unable to cope when headlines spit out the wrong way. People fall to pieces over news stories, often ahead of their real-world problems. We want you more invested in Terri Schiavo or Brett Kavanaugh than your own family relationships. It’s madness, and we’d never treat you this way—if it weren’t the best way for us to make money.

Soviet programmers brought in bawdy soap operas to dub from Latin America, and just before the collapse of the USSR, introduced an emotive, brightly lit Wheel of Fortune spinoff that’s on air to this day.

This is a profound expression of political instability at the top of our society. There is a terror of letting audiences think for themselves that we’ve never seen before. There’s no, “Go back home tonight, rest, and think it over.”

You’ll soon become dependent on the cycle, to the point where you’ll lose the ability to dispute what you’re being told, because disputing would mean diluting the bond with your favored news sources. Once you reach this point, you’ve entered the realm of belief, as opposed to conclusion. This without a doubt is a form of religious worship. It’s what was being parodied in the movie Network, in which an anchorman who loses his mind and begins telling the truth on air is swallowed up and turned into the biggest hit show in the country.

Listening in anger to your favorite political program, you will act like a person who is shaking a fist at power, when in fact you’ve been neutralized as an independent threat, reduced to a prop in a show.

A religion becomes a cult when it doesn’t allow the testing of its premises. Cronkite’s “See you tomorrow!” model, encouraging you to return to mental autonomy, disappears. Mentally, they don’t want you ever leaving the compound now. No interacting with suppressive persons!

Social media has wildly enhanced the illusion that there’s no life outside news. Once upon a time, you didn’t know who reporters were once they put the microphone down. You rarely knew what they stood for, whether they were jokesters or bullies, conservative demagogues or mellow hippies. Now reporters never go home. They are on social media day and night. They share everything, from pictures of their cats to takes on the North Korean nuclear crisis.

Their basic idea: news media is a synthesis of elite concerns. It has to serve the ends of

media owners by making a profit, or enhancing the prestige of a larger profit-making network. It also has to coincide with values of advertisers, strengthen the relationships between top news agencies and high-level government sources, and serve the propaganda aims of those sources, often by organizing the population against a common enemy.

The news at its core is still a vehicle for advancing elite interests. Most of the filters still hold. But the model has been disrupted in one key way. As Chomsky notes, the idea of anti...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

This is why the biggest change to Chomsky’s model is the discovery of a far superior “common enemy” in modern media: each other.

The divided nature of our media acts in part to prevent us from seeing similar cracks widen in our own empire.

We can’t allow attention to flag for even a moment because the evidence of political incompetence and corruption is so rampant and undeniable.

These and a hundred other problems are common to the entire global population, not just Republicans or Democrats in the United States.

In order to satisfy everyone up top with a say in the matter—from advertisers, to Internet distributors, to politicians who drive news, to political donors—this has to be the outcome. Anything but the most intense kind of reality-show civil war would leave Americans free to stare their real problems in the face.

This is why you should always be suspicious of emergencies, indeed of anyone who tells you to worry about things you can’t control.

The exercise becomes intellectually exhausting for the ordinary person, something both government officials and media executives count on.

some of the details dumped on the public wouldn’t “hoodwink a real expert.” But that wasn’t the person they needed to fool.

but Iraq was a real milestone. It set the stage for future stories that urged audiences to accept complex sets of plots and subplots on faith.

Jonathan Chait of New York, a human wrongness barometer if there ever was one, supported the invasion in ’03, then wrote a snippy column ten years later warning that “sweeping out… the existing thought, and existing thinkers” who’d erred on Iraq (read: him) would be a “myopic” response.

Evidence was always over the next hill. It was a pioneering effort in a kind of journalistic Ponzi scheme, in which news organizations justified banner headlines in the present by writing checks against a balance of future revelations.

Instead, reporters somehow failed to notice that key elements of the argument for invasion had been made public long before 9/11, by intellectuals with close ties to Bush.

Invading wasn’t a response to the collapse of the Twin Towers, or an effort to keep safe from the spread of WMDs in the terror age. It was step one in an ambitious new foreign policy vision articulated before most people even heard the name “Osama bin Laden.”

Most are unaware that neoconservatives were disappointed Democrats, who defected to Republicanism over LBJ’s social programs and George McGovern’s antiwar stance.

In 2009, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair admitted he would have backed an invasion of Iraq even if there had been no WMD issue.

The Bush administration at first didn’t want the UN involved; the British said they couldn’t support the invasion without the fig leaf. So they got to work on a new argument based on Saddam Hussein’s defiance of UN inspections, and his possession of weapons of mass destruction.

The Brits released their intelligence findings via a pair of dossiers, one in September of 2002 and another in February of 2003. In response, somewhere between six and thirty million people worldwide were unconvinced enough to march in the streets in protest on February 15, 2003 (I was one).

Remnick also stressed Saddam’s “use of chemical weapons on neighbors and his own citizens,” then went further back in history in search of a tyrannical comparison. This technique often comes up, by the way, when a dictator gets in America’s way. The ruler in question is often described as a deluded fantasist, determined to undermine the benevolent Western order in search of past nationalist glory. He is an Ozymandias, indifferent to the accumulating sands of progress.

If any one of these people had included as a possible variable the notion that intelligence chiefs were lying to them, the paucity of the case for war would have come into focus rather quickly, as it did for the millions of people around the world who protested.

You might get a reporter to apologize for getting a fact wrong, if you hassle him or her enough over a period of many years. But they never apologize for the subtext in which their errors came wrapped. The usual play is an “I was right even though I was wrong” retrospective, often involving not-inconsiderable revisionist history.

The idea that “nobody got that story completely right” is a worse legend than the idea that Saddam had weapons. Nobody got that right? Millions and millions got it right.

The punchline is that the plagiarism job was uncovered before the invasion. By February 7, 2003, a month before attack, Tony Blair’s government was under fire. The “dodgy” dossier, supposedly a high-level intelligence analysis written by MI6, was actually put together by “mid-level officials” from… Blair’s communications department!

When the expert authors turned out not to be intelligence analysts but mid-level press officers, this was an admission that the messaging operation’s real target was not Saddam Hussein but the media itself. That this crude cut-and-paste job was not even undertaken by the office’s best people should have told reporters something else, something profoundly insulting they should have taken personally. But they didn’t.

This kind of thing went on repeatedly during the Iraq debacle. The press was used as a laundry machine, tossing dirty information made “reputable” by attaching it to names of prestigious news agencies. This trick, delivering information as unnamed sources and then later referring to reports as having been independently confirmed, made reporters part of the con. The game should have been clear then. What possible excuse could the New York Times have for continuing to take the war seriously?

foreign ally might be more willing to “sex up” intelligence, especially if the target audience is someone else’s media, with whom those agencies have no relationship. This is a critical angle non-journalists probably don’t get as easily—it’s harder for officials to lie to the local press, since they’ll have to keep talking to them in the future. If a key fact or two can be fobbed off on a foreigner flown in for a few days, so much the better.