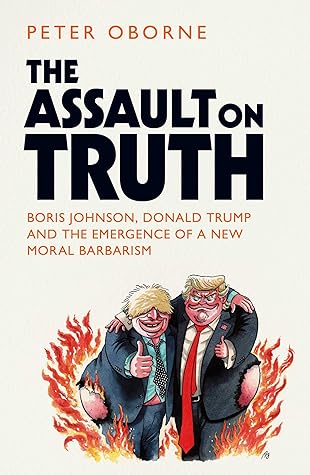

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Peter Oborne

Read between

May 1 - May 2, 2021

The New Journalism was especially stimulated by the ‘gonzo journalism’ of Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Thompson wrote that ‘fiction is a bridge to the truth that the mechanics of journalism can’t reach’, adding that ‘you have to add up the facts in your own fuzzy way’.

was Boris Johnson who possessed the confidence and creative genius to inject gonzo journalism into mainstream British political reporting.

He landed in Brussels thirty years ago in the same spirit as Hunter S. Thompson in Las Vegas, though without the drugs.

At the heart of his reporting was Thompson’s insight that fiction ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

By some margin the most brilliant political journalist of his generation, with a talent that at times crossed over the line to genius, Johnson infuriated ri...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

But at the heart of his reporting work was a repudiation of the ethics that until then had defined journalist values at Westminster: fairness, accuracy, scruple, scepticism, fact checking.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, identities were collective: regiment; trade union; community; church; country; family; political party. The most admired qualities were duty, courage, self-sacrifice – all of which required individuals to submerge their personalities in the interests of an institution or the nation.

Johnson abandoned all of these for a narcissism that mocked the style of straightforward, sober, serious, self-effacing politics of the post-war era.

For him, politics was a personal story which saw the evolution of Britain’s first gonzo political journalist into our first gonzo prime minister. The parallels with Donald Trump are instructive.

The Art of the Deal. He hailed a quality which he called ‘truthful hyperbole’ which, said Trump, ‘plays to people’s fantasies’.

Like so many other celebrities, he invited his audience lose themselves in a fantasy world created by him, in which he alone defined success and failure, truth and falsehood.

Britain and America carried out a joint experiment. Truth-twisting techniques drawn from show business, which proved stunningly successful in marketing political campaigns, are now becoming part of government.

The coronavirus pandemic is the most tragic example of why techniques drawn from show business, though they can be an effective campaigning tool, do not work in government.

‘The pandemic cannot be fought with lies and disinformation, and neither can it be with hatred and agitation. Fact-denying populism is being shown its limits. In a democracy, facts and transparency are needed.’

Neither the prime minister nor the president possessed the moral seriousness to cope with a public health catastrophe like coronavirus.

both men were slow to grasp that a problem existed at all.

Donald Trump’s conduct was grotesque. At least Boris Johnson did not refer to coronavirus as a ‘hoax’,I invite people to inject themselves with bleachII

But Johnson and his ministers certainly did systematically mislead voters, repeatedly boast about imaginary achievements, and exploit the Tory government’s phalanx of press support to shift the blame,IV rather than owning up to errors which cost the lives of thousands.

Barely a month before the pandemic started, Johns Hopkins University published a study of global readiness to deal with health emergencies,

It went on to rank the United States and the United Kingdom as the two countries in the best position to handle a pandemic.

Yet the Johns Hopkins experts were wrong in their predictions. Britain and the United States have been two of the worst-performing countries in the world.

At the heart of Johns Hopkins’s miscalculation was a failure to take into account political leadership.XII

Right from the start, Germany took the World Health Organization (WHO) advice,

By contrast, the UK was slow to start testing.

Prime Minister Johnson failed for a long time to grasp the significance of the crisis.

With Germany (and most of Europe) locking down, Johnson was effectively in denial.

By the time he had re-emerged, it was clear for everyone to see that the British government had made serious errors in the early handling of the virus.

This phase of the crisis brings me to the second area of contrast between Johnson and Merkel. With events moving against them, Johnson and his ministers resorted to a series of falsehoods.

Throughout the coronavirus crisis, Angela Merkel was straight with the German people. She was calm, pragmatic and open.

It is excruciating and a matter of deep national embarrassment to compare Angela Merkel’s good sense with never-ending iterations of bombast, exaggeration and falsehood from Boris Johnson once he had returned to work towards the end of April.

At this point the government entered the realm of fantasy. On 1 May Johnson and his health secretary claimed that Britain had met its target of 100,000 daily coronavirus tests.XXXVI This was a fabrication.XXXVII

The issue got so bad that Chris Hopson, chief executive of NHS Providers – the membership organisation for all of England’s 217 ambulance, community, hospital and mental health trusts – told Johnson to stop the rhetoric. On 7 June, Hopson said: ‘The real concern is that we don’t have that same degree of trust, because we’re not having the kind of honest and open debates that we need. We seem to be resorting to kind of fairly cheap political rhetoric about stuff being world-class, when it clearly isn’t.’

Throughout the crisis, government ministers insisted that the UK’s response had been without fault. A mantra developed: government had ‘taken the right steps at the right time’.

This was nonsense. The government was slow to stop public events, ditched the test and trace strategy early only to return to it later, wasted time with a dangerous herd immunity strategy, missed the deadline for a joint EU ventilator procurement scheme,XLIV failed to introduce its track and trace app on time. The list could go on.

And some of the lies told by the government were very dark. Take the statements about care homes made by the prime minister and his health secretary, Matt Hancock.

In this chapter I have shown how this technique of blame shifting and deceit was a core part of Boris Johnson’s response to coronavirus.

In the next chapter I will show how this strategy stretched across almost every part of government, evolving into a determined attack on the nature of the British state itself.

While there is no doubt that Johnson is both deceitful and amoral, the prime minister’s war on the truth is part of a wider attack on the pillars of British democracy: Parliament, the rule of law and the civil service.

There is a reason for this. Truth and liberal democracy are intertwined.

When truth is defined by the rulers themselves, the people lose all ability to pass judgement on them.

Ministry of Truth, whose sole purpose is to ensure that every single ‘fact’ available to the population supports the narrative of a wise and successful ruling party.

succeeds in its purpose. Citizens believe the Party propaganda even when it

‘From a totalitarian point of view history is something to be created rather than learned,’ wrote Orwell, adding that totalitarianism demands ‘the continuous alteration of the past, and in the long run probably demands a disbelief in the very existence of objective truth’.III

Another example of this was Dominic Cummings’s claim that ‘for years, I have warned of the dangers of pandemics’. He added: ‘Last year I wrote about the possible threat of coronaviruses and the urgent need for planning.’ It later emerged that this was not true and that he had secretly updated his blog in order to give authenticity to his false claim.V

Finally, truth matters for democracy itself. Political deceit is theft.

Governments who lie to voters are treating us as dupes rather than equals.

Johnson does not value integrity.

The most illustrious victim (so far) is the Cabinet secretary, the most senior civil servant in Britain and the ultimate symbol of public integrity.

I described at the end of the chapter above how government briefers arranged a vicious and dishonest whispering campaign at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, using media allies to place the responsibility for government failures on others, while leaving ministers with clean hands.