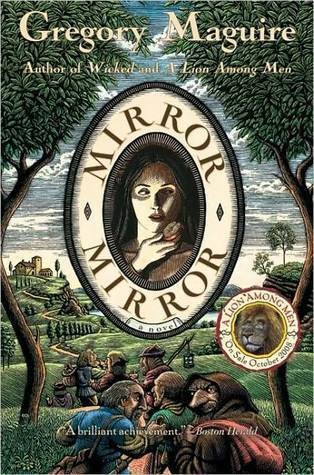

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

But I have come out of one death, the one whose walls were glass; I have awakened into a second life dearer for being both unpromised and undeserved.

The eye is always caught by light, but shadows have more to say.

Fra Ludovico: The stories of heaven belong in the heads of children. If, as children grow, the stories evaporate?—oh well. They leave behind a residue of hope that changes how children behave. Primavera: That stinks more than your chamber pot.

(The merchant had been a widower and his dead wife wouldn’t know he was buried with another woman until purgatory, when everything was too late to change anyway.)

María Inés de Castedo y Nevada.

You can see the noisy stream, the rushes, the wrens at their work, the hills beyond. But what don’t you see?” “I don’t see why you have to leave again,” she said.

“Someone has sketched schemes of sex between whores and morons,” said Primavera. “Only a moron would have sex with a whore,” said Fra Ludovico. “Bianca, I forbid you to examine these diagrams. You would weep with fright and grief.” “I can see her laughing herself sick,” said Primavera. “Or getting ideas. Usually, for the sake of honesty, I have to chop the carrot in half so as not to get a young girl’s hopes up.” A pause. “There’s really nothing to compare to a squid.”

“You don’t know what you pray about,” snorted Primavera, “that’s why you won’t tell us. You pray for a reason to pray, that’s all. And it doesn’t come.”

But our lives are longer than human lives. Just yesterday Primavera Vecchia was slipping off the lap of her grandmother and landing in the basket of onions and pissing on them. They made a better soup for it, those onions. Today Primavera is hairy of chin and tomorrow no one will remember who she was.

“But Prince Dschem offered news of something older. Something more perfect. So desirable that its very existence had been kept hidden for centuries. A sprig of the Tree of Knowledge, out of the very orchard of Eden from which our kind has sprung.”

“Where is this treasure?” said Vicente. “Prince Dschem told me,” said Cesare. “And then I left. Without him.” “He died a month later, in Naples,” said Lucrezia flatly. “Our detractors in Rome say he was poisoned with a particular slow-acting powder that only we Borgias know how to produce.”

“And now we come to the reason for our visit,” said Cesare. “I want you to go collect the sacred fruit of Eden and bring it to me.”

Fra Ludovico, who found that sharing his cell with the Holy Spirit was a bit too close for comfort sometimes, was surprised to notice that his wariness of the Duke was coupled with curiosity. A rogue with a passion for prayer. See how he furrowed his brow in devotion, how the sweat drew hot lines down his forehead. Fra Ludovico had to look away in order to concentrate on his sacred business.

May she go in safety, thought Fra Ludovico. May her brother go in safety. May they go soon.

“Cesare may break his promises,” said Vicente coldly, “but I will hold you to yours, Lucrezia Borgia. You are no goose. You know I mean it.” He had her. She said, “I will keep my word, then. I will see that your household is maintained and your child protected.”

Here was a dwarf with his hand on his hip.

The prelate was feeling his age. The years following the departure of his master hadn’t been easy. First, Lucrezia Borgia had dismissed the overseer that Don Vicente had assigned to watch after things. Dismissed or removed from the district, it was unclear which, but in any case the hapless local governor was gone as gone.

for all his timidity, his fondness for the true daughter of the house prevailed.

She was about eleven years old now. She begrudged the sacrifice she’d been required to make, but she wasn’t a fool: she could tell that showing contempt to Primavera or Fra Ludovico would be misdirected. She misbehaved mildly, as was fitting for her age.

She couldn’t make herself pass. Not yet. Sometime when the bridge wouldn’t thump at her, when the water wouldn’t wink at her: then she would cross it. But today—and in several other tries that summer—she failed, and kept failing. Was it her promise to her father that waited under the bridge, with its hairy hand?

She made a lazy inspection of the farm—the accounts, the state of the orchards, the gooseboy and his geese, the buildings and outbuildings, and in the evening she came to a conclusion. She decided that Bianca no longer needed a nurse, and Primavera could be let go.

“I lost both sons to Cesare’s wars,” said Primavera pointedly.

My only grandson is a hunter, and seeing what conscription did to his father and uncle, he keeps out of the way of the condottieri.

“Send her to me,” said Lucrezia. “She has her supper to eat,” said Primavera. “I’ll send her to you when she’s fed.” “You won’t correct me, “ said Lucrezia. “You won’t dare.” “I beg your forgiveness with all my heart, and trust in your legendary mercy,” said Primavera dryly. She took herself off to the kitchen, histrionically wheezing on the stairs.

Primavera called Bianca to come clean her hands and wipe her face. Then she bellowed for Fra Ludovico to come bless the damned meal before it got cold.

Hello, this is I, and these my arms and legs, which are useful, and this inconvenient hump is my sorrow, which is less than useful, but I’ve learned how to hump it about with me, so pay it no mind.

“Well, she’s grown then,” said Lucrezia crossly. “I forgot that children grow.” “What a natural mother you are.”

Bianca knew enough not to come forward. “A mouse doesn’t accept invitations from a cat,” she said politely. “A mouse wouldn’t know how to converse with a cat.” “She’s got the trim of your sails!” Lucrezia hooted with unprincipled glee.

Children didn’t regularly sit in the presence of their betters—primarily so that they could get a head start should they have to run for safety.