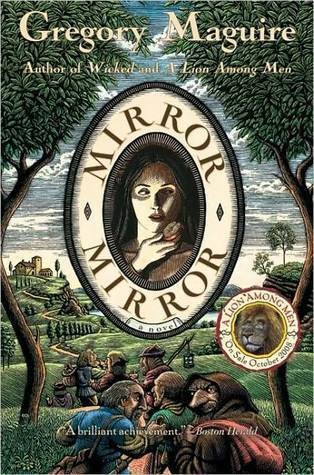

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“I’m schooled in my letters,” Bianca admitted, “but not so that I can read in the language of my grandsires.”

“I was the daughter of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia,” she snapped. “I’d have been engaged in utero, had it benefited the family fortunes, as you know very well. Despite Vicente’s implication of wealth and connections, the de Nevada family is neither powerful nor clever. This letter may be a ruse to confound us.” “We weren’t meant to see it,” said Cesare. “Of course we were. It’s written in Spanish. Who else at Montefiore would have been able to read it?”

And he’d found what he was sent to find, and been discovered in the process, and tossed like a bug into a hole, and he waited to die, and wanted to die, and he didn’t die. So was there a God or wasn’t there?

He could tell they thought the boat was bewitched. The darker it grew, the more resistance the boat developed, until at last the brothers had had enough. They fell upon Vicente and tossed him into the sea. Though he was surprised, he was hardly disappointed, as he had come this far in order to go farther. So he struck out for land, and with backward glances saw the brothers bringing the boat around without further difficulty.

Vicente never heard a human voice raised in anything but apparent prayer until the day an ancient patriarch came across him with his hand on the door of the monastery’s treasury. The old man had shrieked like a woman, and monks appeared from nowhere, fierce as crows, to settle down upon Vicente and protect what was inside. Down into the dungeon he had been thrown.

The stones must not have been as deaf as he imagined, for they answered, “God keeps His own counsel, but the stone hears you.” He didn’t make a further remark, for to converse with the stones of his prison must be a sign of his mental collapse and maybe good Brother Death would show up at last. It was about time.

After her father was elevated to the throne of Peter, the Vatican’s apartments and offices were as crowded as alleys on market day. The commodities on sale were pardons, favors, indulgences to shorten purgatorial jail sentences.

Thus had Vicente come into possession of Montefiore, after Lucrezia, privately, had had the previous owner smothered, to ensure the premises were available for new occupants.

In due course, she had given birth to Rodrigo, of more honorable lineage, of better disposition and capabilities than the Punishment. To protect him she had him raised far from herself too. There was reason, in his legitimacy, to worry about his prospects, and she wouldn’t see him besmirched by too close an association with her.

“It was an accident,” she insisted. “You were standing like a docile sweet orphan and a vase flew into your head by accident?”

“If you let me go,” she said, and faltered. “. . . you will run,” he said, completing her sentence. And then she understood him. She stopped and stood still. He let her go.

But lore was only lore, a system of thinking decayed from some more ancient, blurry hypothesis, deteriorating toward a superstitious tic or ridiculous custom.

What the exchange had done for him—to him—became evident only in time. He was a hunter, a castaway in the shrinking forests of late medieval Italy, and, single-minded and uneducated, he’d been bred and raised to hunt and kill for food. And now he couldn’t perform the duty without a certain cost to his spirit.

But he didn’t kill without dread and shame, realizing that the lower creatures, the deer and fowl and boar, the rabbits, the wild pigs, all resisted, all preferred their lives to their deaths.

And wondering, all along, in the crusty margins between dreaming and waking, if the unicorn was still waiting, or if it had found a more capable murderer.

“The heart of the woods,” he said to Lucrezia when, the next morning, he handed her the wooden casket she had requested.

We had once been the number one more than seven, we clots in the earth’s arteries. But the noisy one left and maybe for need of him we were stricken with attention. When we were only seven, there was something wrong.

We had no names. We couldn’t count until one of us left, and then we learned to count to seven, and to figure out odd from even.

Perhaps that is why humans rely on the mirror, to get beyond the simple me-you, handsome-hideous, menacing-merciful. In a mirror, humans see that the other one is also them: the two are the same, one one.

And so we had made a mirror, and in our foolishness lost it, and the one who set out to reclaim it had never returned.

Indeed, until recently, we wouldn’t have known to identify 1 from 7, or 4 from 6, or a pillow from a saw. In our efficiency we were blind. But one of us left, and we eventually noticed that he was gone.

When her eyelids did flutter, we became shy, as if caught in a common sin, though without the individual soul to save or lose, we were as incapable of sin as a scorpion.

“I didn’t quite hear the question; stone is hard of hearing. So you can call me Deaf-to-the-World, thank you for asking.”

“Stone can’t speak, so I’m Mute, Mute; always was Mute, always will be Mute. MuteMuteMute. Why do you even bother to ask? Why do you bother me so?” MuteMuteMute, it seemed, would have liked very much to talk, and was therefore irritable at being reminded of his debility.

This is how we were born. She sat amidst us, more or less naked as a human baby, looking, but it was we older brothers—older than trees, older than wind, older than choice—who were born in her presence. Blindeye, Heartless, Gimpy, Deaf-to-the-World, MuteMuteMute, Bitter, and Tasteless: incomplete sections of each other, beginning our lumbering life of individuality— —beginning our lumbering lives.