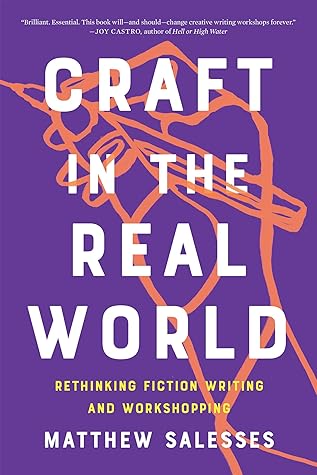

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Language has meaning because it has meaning for someone. Meaning and audience do not exist without one another.

Adoptee stories also frequently feature coincidence and reunion. Maybe that is why I am drawn to external causation, to alternative traditions, to non-Western story shapes.

Cortázar calls plot, that string of causation, an inherent danger to the realistic story. “Reality is multiple and infinite,” he writes, and to organize it by cause and effect is to reduce it to a “slice.”

Plot is always a departure from reality, a symbol of reality. But the power of stories is that we can mistake the symbolic for the real.

Craft that pretends it does not exist is the craft of conformity or, worse, complicity.

Craft is in the habit of making and maintaining taboos.

Robert Boswell said one could consider tone as the distance between the narrator and the character.

What is important to Aristotle is that what you feel can teach you what you think. Emotion is intelligent. Where we must part from Aristotle is in our current understanding that emotions are often cultural, not universal or instinctual.

If we think of plot as acceptance or rejection of consequences, we take into account constant negotiations with power.

the point is that the story arc is always read together with the character arc to create meaning.

To that end, an exercise that has helped my students and myself with characterization, plot, world-building, and so forth, is to write a list of every decision a character makes in a story, in order, skipping nothing, not even what they choose to wear that day or negative choices (things they choose not to do).

But really what makes a character the kind of person they are is: difference in relation to others, whether that is difference in type or difference in attitude.

Just as any story begins with something out of the ordinary (a journey, a visit from a stranger), any chara...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Characters (fictional beings that require meaningful choices) always exist in relation to each other (and the world).

One of the most useful tricks I learned in my MFA was Margot Livesey’s response to a believability complaint: “Just make someone in the story question it.” If a character within the story brings up the objection, then readers are often happy to let someone else make it. This also gives the writer a chance, whether she uses it or not, to provide context.

An unusual event does the most work for a story when it involves the development of belief or disbelief—once I heard Kazuo Ishiguro talk about strangeness as a dial, that he thinks of it as turning the dial up or down, that if a tiger walks into a boardroom and everyone freaks out, the dial is turned down to our “reality,” and if everyone ignores the tiger, the dial is turned far up.

We risk something in each creation simply by creating a version of ourselves on the page. That risk is not for sale, but it is on display.

Ask yourself some of these questions: What is your protagonist aware of? What forces shape her/his/their awareness? What is the narrator aware of? What forces shape that awareness? What awareness shapes the idea of who the implied author is? What awareness shapes the idea of who the implied reader is?

For prolepsis (flash-forwards) and true/false mystery (mystery shared by the characters vs. mystery only for the readers, e.g. whodunit in a first-person detective novel):

You might think of the basic fairy tale structure: Once upon a time Every day One day And then And then And then Etc. Happily ever after