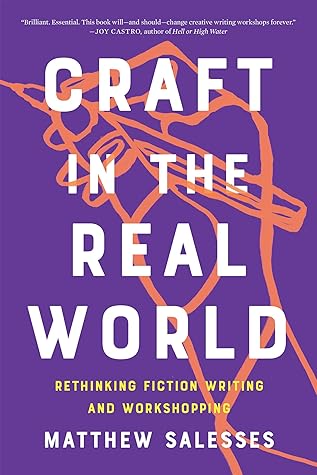

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 6 - February 7, 2021

Race, gender, sexuality, etc. affect our lives and so must affect our fiction. Real-world context, and particularly what we do with that context, is craft.

We must reject the mystification/mythification of creative writing. The mystical writer uses the myth of his genius to gain power. He (since it is almost always a he) benefits from keeping up the illusions that he has natural talent and that writing cannot be taught. If writing is not beholden to culture, then he is free from the constraints of actually being a part of (or responsible to) the world in which he and his readers live.

Writing that follows nondominant cultural standards is often treated as if it is “breaking the rules,” but why one set of rules and not another? What is official always has to do with power.

Culture stands behind what makes many craft moves “work” or not, and for whom they work. Writers need to understand their real-world relationship to craft in order to understand their relationship to their audience and to their writing’s place in the world.

Craft is about who has the power to write stories, what stories are historicized and who historicizes them, who gets to write literature and who folklore, whose writing is important and to whom, in what context.

To tell a story about a person based on her clothes, or the color of her skin, or the way she talks, or her body—is to subject her to a set of cultural expectations. In the same way, to tell a story based on a character-driven plot or a moment of epiphany or a three-act structure leading to a character’s change is to subject story to cultural expectations. To wield craft morally is not to pretend that those expectations can be met innocently or artfully without ideology, but to engage with the problems ideology presents and creates.

If we think of plot as acceptance or rejection of consequences, we take into account constant negotiations with power. Acceptance and rejection are often emotional, not active. Sometimes a character’s negotiations with power are part of a string of causation and sometimes not. To put plot in terms of acceptance and rejection is also to put plot in sociocultural context. Acceptance and rejection are cultural—they depend on positionality, geography, mental health, familial values, trauma, etc.

A large part of that message is this: How much of the conflict you face is caused by your own actions? How much is on you? This is a question that has every implication for how to read the contexts of race, class, gender, ability, sexuality, etc. Conflict presents a worldview, along a spectrum from complete agency to a life dictated completely by circumstance.

But really what makes a character the kind of person they are is: difference in relation to others, whether that is difference in type or difference in attitude.

To say a work of fiction is unrelatable is to say, “I am not the implied audience, so I refuse to engage with the choices the author has made.”

Perhaps one of the reasons a white author might have trouble writing a protagonist of color is that the author is noticing the wrong things. The author is thinking of setting as a character of its own rather than reliant on character.

the Workshop is supposed to spread American values without looking like it is spreading American values, what better craft for the job than the craft of hiding meaning behind style?

but a typical school reading list does suggest that most Americans are far more versed in a single tradition of fiction than in any other. If we read a few translations or foreign classics, they are often compared to the tradition of Western psychological realism (in it or not in it) rather than read within traditions of their own.

The tradition of stories within stories, looping or intersection or nesting or framing or so forth, in which we could include contemporary novels like the American middle-grade novel Where the Mountain Meets the Moon, by Grace Lin, and the Chinese literary novel Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out, by Mo Yan, is a tradition that goes back at least to the Thousand and One Nights. A better understanding of this tradition would, for example, have allowed critics to see recent novels like Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life or David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas as Western adaptations of long-held Eastern

...more

A useful workshop considers who “the reader” is for each particular writer and therefore approaches each particular story on its own terms. Otherwise, intentions are not reflected back to the author but forced on her. A common complaint about the proliferation of MFA programs is that they breed generic writing. The real danger is not a single style, it’s a single audience. It is effectively a kind of colonization to assume that we all write for the same audience or that we should do so if we want our fiction to sell.