More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

War is always attractive to young men who know nothing about it, but we had also been seduced into uniform by Kennedy’s challenge to “ask what you can do for your country”

By autumn, what had begun as an adventurous expedition had turned into an exhausting, indecisive war of attrition in which we fought for no cause other than our own survival.

Most of all, we learned about death at an age when it is common to think of oneself as immortal. Everyone loses that illusion eventually, but in civilian life it is lost in installments over the years. We lost it all at once and, in the span of months, passed from boyhood through manhood to a premature middle age.

but I could not deny the grip the war had on me, nor the fact that it had been an experience as fascinating as it was repulsive, as exhilarating as it was sad, as tender as it was cruel.

Anyone who fought in Vietnam, if he is honest about himself, will have to admit he enjoyed the compelling attractiveness of combat.

no fire be directed at unarmed Vietnamese unless they were running. A running Vietnamese was a fair target. This left us bewildered and uneasy.

we think that if somebody gets killed tomorrow, he oughtta be laid out and the company marched past to look at the body. Then we’ll see if anybody’s still got something to laugh about.”

The platoon sergeants had recovered from their funk and were cheerful in the resigned way of men who know they have no control over what is going to happen to them.

where we were going, to that frontier between life and death, but none of us wanted to listen to them. So I guess every generation is doomed to fight its war, to endure the same old experiences, suffer the loss of the same old illusions, and learn the same old lessons on its own.

The marines are all in the same state of mind as I, “fed-up, fucked-up, and far from home.” Their arms are tanned a deep brown,

expressed what may have been a collective emotion. “They’re young men,” he told me. “They’re just like us, lieutenant. It’s always the young men who die.”

for all its intensity, our Marine training had not completely erased the years we had spent at home, at school, in church, learning that human life was precious and the taking of it wrong.

the real thing proved to be more chaotic and much less heroic than we had anticipated. Perhaps it had been heroic for Lemmon’s platoon, but for the rest of us, it amounted to a degrading manhunt; pulling bodies out of the mud had left us feeling ashamed of ourselves, more like ghouls than soldiers.

The sight of mutilation did more than cause me physical revulsion; it burst the religious myths of my Catholic childhood. I could not look at those men and still believe their souls had “passed on” to another existence, or that they had had souls in the first place. I

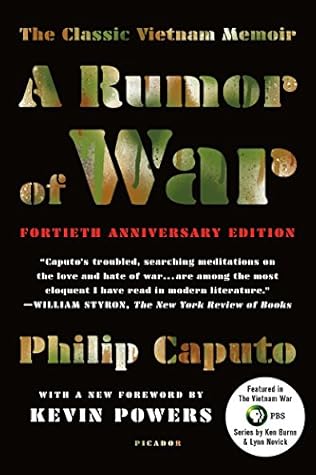

To return to the present, A Rumor of War and five other books published at about the same time—Larry Heinemann’s Close Quarters, Michael Herr’s Dispatches, Ron Kovic’s Born on the Fourth of July, Tim O’Brien’s Going After Cacciato, and James Webb’s Fields of Fire—broke the ice and made the Vietnam War a legitimate