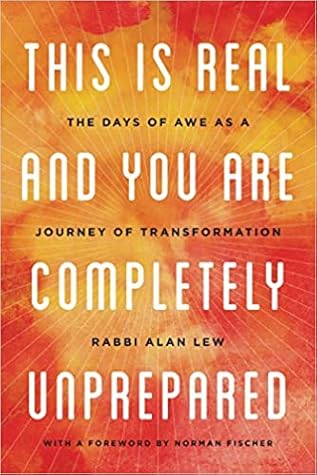

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Alan Lew

Read between

August 14 - November 26, 2023

Fullness and decline are intimately linked. The end of one is the beginning of the other. Conversely, decline and destruction necessarily precede renewal; tearing down is necessary before rebuilding is possible.

This image, this series of fasts, tells our bodies and our souls the story of the encroachment of emptiness: the story of impermanence.

But the truth is that if the Temple had never been destroyed, the renewal Judaism needed so badly could never have taken place. If the walls of the Temple had never fallen down, the fundamental spiritual impulse of Judaism—the powerful emptiness at its core—may very well have been smothered.

So the Torah tells us seven times. Vneifen, u-finu—and they turned, now you turn.

Life bets that we won’t be willing to endure the suffering it requires. Life bets that we will try to shut out the suffering, and so shut out life in the bargain.

Our suffering, the unresolved element of our lives, is also from God. It is the instrument by which we are carried back to God, not something to be defended against, but rather to be embraced.

is being blown to call you to wakefulness. You awake to confusion.

only in proportion to the time and energy you have devoted to preparing for this encounter.

Parshat Re’eh, the weekly Torah portion we read as the month of Elul begins. Look. Pay attention to your life. Every moment in it is profoundly mixed.

Every moment contains the capacity for good and evil, life and death, a blessing and a curse, and everything depends on our choice.

We must set aside time each day of Elul to look at ourselves, to engage in self-evaluation and self-judgment, to engage in cheshbon-ha-nefesh, literally a spiritual accounting.

God isn’t as easy to deceive as we are. God has the annoying tendency of taking everything into account and not just the aspects of our experience that make us look good

Most of the time, the negative, destructive things we do are done unconsciously. The remedy for this, of course, is simply to become more conscious, more aware.

Standing before God, we see ourselves whether we want to or not.

in the month of Elul, when we are bidden to set aside time each day to look inward, to take account of ourselves spiritually.

When we were speaking of prayer, it was the words of the prayer book that we were trying to focus on. Here in meditation, it might be the breath and it might be the body, it might be a mantra and it might be a visualization, but in all these cases, the result is the same: we come to see ourselves more clearly. We come to see the things we either will not or cannot see.

Meditation helps us inhabit ourselves more deeply, and it constantly throws us up against the very things about ourselves we are trying not to see.

Just choose one simple and fundamental aspect of your life and commit yourself to being totally conscious and honest about it for the thirty days of Elul.

think what the Torah is saying here is that we should only eat until we are satiated.

We should eat only what our soul desires, only what our body requires, and not what our unconscious desires bid us to eat.

Eating is a fast palliative for the stress that overwhelms us, a surrogate for the emotional and spiritual nourishment we need and never receive, a way of feeling our physicality in a world that all too rarely permits us to do so. In short, the act of eating is a gateway to some of our deepest feelings.

So we can pray, we can meditate, and we can set aside a moment every day for reflection. Or we can simply choose one thing in our life and live that one small aspect in truth, and then watch in amazement as the larger truth of our life begins to emerge. The truth is, every moment of our life carries with it the possibility of a great blessing and a great curse, a blessing if we live in truth, a curse if we do not.

Parshat Shoftim, which we read during the first or second week of the month of Elul,

According to the Iturey Torah, there are seven gates—seven windows—to the soul: the two eyes, the two ears, the two nostrils, and the mouth. Everything that passes into our consciousness must enter through one of these gates. So at the deepest level, the passage cited above has nothing to do with establishment of a system of judges and courts, but deals rather with being mindful of the process of consciousness itself.

In my work as a hospice chaplain, I often witnessed the irresistible urge people have to tie up loose ends as death approaches—to leave their checkbook balanced, to make their funeral arrangements, to finally confess to something that has been on their conscience, to make reconciliation with a friend or a loved one. The urge to complete unfinished business, to tie up loose ends, is one of the strongest forces in nature, and God help anyone who stands in its way.

So while we are conducting spiritual inventory during Elul, we might begin by asking ourselves, What are the loose ends in my life? How is my mind torn? Where are the places my mind keeps wanting to go? What is the unfinished business in my life? What have I left undone? When we look out at the world through a torn mind, our experience of the world is torn.

So when we are taking inventory, one of the things we might decide is that we have to simplify our lives. We have to do fewer things.

Our feelings and our spiritual impulses flow freely beyond the boundaries of the self, and this is something that each of us knows intuitively for a certainty.

We know that emotions are contagious. We know they do not honor the boundaries of self, and even seem to mock them. We all have the same heart.

Don’t look off in the distance, and don’t look outside yourself either, the Torah is telling us, look at your own heart. Don’t look out the window; look at the window itself.

But the problem is never the suffering. The problem is our feeling that we have to do something about it.

Suffering is just suffering, a feeling that only wants release from the imprisonment of the self—a spiritual impulse that often ennobles, and that like any feeling, carries its own considerable burden of beauty with it.

Parshat Ki Tetze, which we read during the third week of Elul,

Images of war abound during Elul.

The Torah never permits too much distance between the values it proposes and the way people actually behave, because it recognizes that to do so would break the connection between our lives and the Torah,

But trying to efface the impulse altogether might not only have been unrealistic, it might have been undesirable.

desire is the basis of our creativity, our productivity.

If we try to push these desires down, they’ll only come up somewhere else. If we kill them off altogether, we may be doing violence to ourselves; we may be killing off the basis of our real creativity.

We’ve learned that if we always act on our desires, on those unmitigated impulses that constantly rise up in our hearts and our minds, then we are doomed to a living death,

Traditionally, Selichot begins with a midnight prayer service on the Saturday night before Rosh Hashanah (or on the previous Saturday night, if there are fewer than four days between that Saturday and Rosh Hashanah) and continues with special prayers of supplication recited by the pious at dawn each day of the following week.

And when my mother reached the piano bench and sat down, she suddenly realized that all her preparations were inadequate for the intense reality of this actual moment, and she completely appled.

And the ax—the key that opens every chamber and brings us directly into the presence of the King, wherever he may be—the ax is the broken heart, for as it says in the Psalms, “God is close to the brokenhearted.”

All of a sudden you hear your own name being called, and you want to cry out, No! No! No! Not now! I didn’t realize this was real. I thought this was just some empty ritual. I am completely unprepared.

This is real. This is extremely powerful, and whatever preparation you might have made now seems utterly foolish, utterly inadequate, as the great voice intones your name, and you hear it reverberating in the great room, and the pages of one of the great books begin to rustle, and you don’t know which book it is.

The presence of God was so thick, and so real, and so absolutely connected to the pain and the anxiety and the biological trauma

It is about you. It is really happening, and it is happening to you, and you are seriously unprepared.

a world in which life and death, blessings and curses, choose us, seek us, find us every moment. And we live with the consequences of our choices.

What makes a difference is that it’s real and it is happening right now and it is happening to us, and it is utterly inescapable, and we are completely unprepared.

Heartbreak is precisely the feeling that we have done our best, we have given it our all, but it hasn’t been enough.

We understood that all our preparations had been inadequate—that the reality we now confronted was so powerful and irresistible that it had blown all our attempts to prepare for it away like so many chaffs of straw.