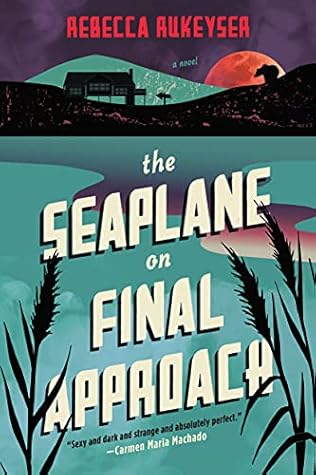

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

During the course of the meal, Maureen became less folksy, primmer. She sat erect, talking about how she homeschooled her children right here on Lavender Island, and taught them to live righteously.

I still had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. I had no drive. But I hadn’t really dabbled in delinquency. I had never gotten it quite right—I bought the wrong hoodie, etc.

when I had only committed the crime of being interested in the dissolute: I was focused almost wholly on the subject of sleaze.

I made lists of sleazy things, and things that other people thought were sleazy but weren’t, like: Cold weather, as opposed to hot weather, was sleazy, because the streets were empty and there was more privacy. Cleavage was sleazy but breasts were not, themselves, necessarily sleazy. Big rigs were sleazy, but so were four-door sedans.

colored Christmas lights out of season are both sleazy.

I was nervous that Kodiak would be too outdoorsy to be sleazy, because sleaze, as I understood it, mainly occurred indoors, often in kitchens.

I knew what would become of me. I’d go back to Kodiak. I knew that things hadn’t gone quite right, that a pulled thread somewhere had started a great unraveling, and after a bit of serious thought, I decided it had something to do with my incomplete and still-faulty understanding of sleaze.

If I could just do it over, I thought, if I could just have another summer, I could get it all right the second time around. Alaska contained more sleaze than the entire lower forty-eight combined.

cloistering. I would spend all summer on Lavender Island, quietly figuring out everything there was to know about sleaze. Then, on November 1, I’d move to the town of Kodiak with my five thousand dollars and find Ed.

She reeked of a love of paper crafts.

and for the oldest sons of the Lawson clan, who were fourteen or fifteen but behaved, alternately, as if they were fifty or five.

Even Chef—who had run off to his tent cabin as soon as the twin skiffs arrived around the spit, motoring toward us with such speed—he was okay. I wished him a nice death.

It was very easy to make everything sound sorrowful, I thought, when you could just turn and stare out at an expanse of cold water that would kill you in fifteen minutes.

But it was her impossible youth—I was very old at eighteen—and the evidences of her stupidity that made her really helpless in my mind. Of course, she might have been bright. I had no idea. It was impossible to extricate the two things—childhood and idiocy—and I got them confused.

cozy.