More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

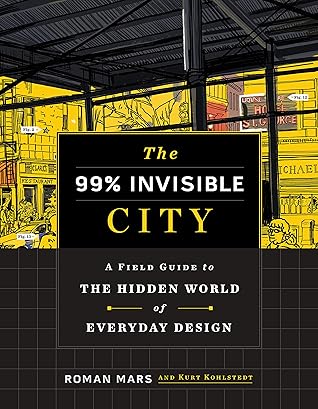

by

Roman Mars

Read between

November 26, 2021 - February 21, 2022

The truth is that the mundane objects we pass by without noticing or trip over without thinking can represent as much genius and innovation as the tallest building, the longest bridge, or the most manicured park.

Before it was the Big Apple, New York was the Big Oyster. The city was built at the mouth of the Hudson River, a fertile estuary packed to the gills with marine life. Scientists and historians estimate that trillions of oysters once surrounded Manhattan, and these bivalves filtered out bacteria from the water and served as a food source for the human population. Beneath the waves, these reefs also provided a less obvious benefit: vital protection against storm surges and coastal erosion.

“The average motorist has no idea how sophisticated these barriers are,” writes engineer Kelly A. Giblin in Invention & Technology magazine. “Their primary function is obviously to separate opposing flows of traffic. But their wedge design was developed to minimize the severity of accidents by restoring control of a vehicle on impact,” Giblin explains. “In a shallow-angle collision—a sideswiping—the Jersey barrier lets the front tire ride up its lower angled face and gets the vehicle back on the roadway with minimal damage.” In other words, the barrier not only reduces head-on collisions, but

...more

It’s hard to look at Jersey barriers and see much more than a lump of concrete formed into a commonsense shape, but everything about them is highly engineered. No single inventor made these dividers what they are today—they are a product of a lengthy and ongoing design process. In a lot of ways, they reflect roadway development more broadly, where intuitive starting points lead down winding paths to solutions that only seem obvious in hindsight.

There is a lot to criticize about the global culture of planned obsolescence, but even well-built things eventually become obsolete. In that light, employing more deliberate, considerate, and sustainable deconstruction methods can offer old architecture a more graceful way to permanently exit the built environment.

Still, many freeways were built at the expense of poor and marginalized communities. Rural towns and suburbs may have benefited from this new network, but it came at a cost for many urban centers and created divisions that still remain.

Cities are rarely the product of a single planner, grand plan, or time period. Urban realities are rarely that simple.

Animals are unlikely to see a return of the world as it was before cities, highways, and dams anytime soon, but for their part humans cannot just plow ahead with development and expect wildlife to cope. In some cases, the best approach maybe simply for humans to get out of the way, but people need to understand that cities and nature are all part of the same ecosystem and that proactive strategies will be needed to help various species survive in a human-centric world.

There is always an aspect of coercion to design. In the commercial world, design is used to get you to buy things you don’t need or use your iPhone in a prescribed way. Cities use design to shape our behavior, too. They employ both subtle and overt forms of influence in public spaces to make life more difficult for “undesirable” populations and to curb “antisocial” behavior. Whether you are the target or a beneficiary of hostile design, it’s crucial to recognize when we’re replacing human interaction with hard, physical, nonnegotiable solutions.

Pollution, health, noise, and space are factors in pro-cycling initiatives, but these efforts also speak to larger questions about urban design history and the very nature of cities. “We must first remember that all cities were car-free little more than a century ago,” writes Carfree Cities author J. H. Crawford. “Cars were never necessary in cities and in many respects they worked against the fundamental purpose of cities: to bring many people together in a space where social, cultural and economic synergies could develop. Because cars require so much space for movement and parking, they work

...more

Criticisms of e-scooters aside, reducing the number of cars in cities in favor of more bicycles and other multimodal transit options is generally viewed as a net positive for citizens and the environment. Still, it is worth keeping a critical eye on what replaces car-oriented space. Activist-led interventions tend to favor the lifestyles of those activists. Cyclists naturally tend to promote cycling infrastructure. The best interventions, however, involve the whole community and use local input to drive designs that will serve a variety of residents with different experiences, priorities, and

...more