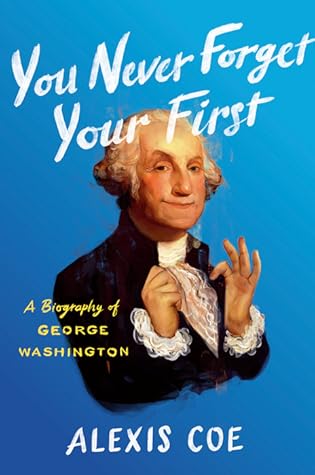

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Alexis Coe

Read between

November 10 - November 11, 2022

By the age of fifty-seven, the unanimously elected first president of the United States had but one tooth of his own left and had long been investing in dentures.

At best, we can say that Washington had a poacher’s smile. His dentists took chunks of ivory from hippopotamuses, walruses, and elephants, sculpted them down, and affixed them to dentures using brass screws. They filled in any gaps with teeth from less exotic animals, such as cows and horses, or—when the Madeira stains weren’t too bad—from Washington himself.

At the age of eleven, he inherited ten slaves from his father, and over the next fifty-six years, he would sometimes rely on them to supply replacement teeth. He paid his slaves for their teeth, but not at fair market value.

Slowly, Washington ceased to be a man and became the embodiment of the nation at its best, most noble and public-spirited.

According to Washington, the animal was “in very poor order,” a startling admission in Virginia, where men who traveled even the shortest distances on foot were understood to be poor. If the animals were hungry, then the future president and his family—and most of all, their slaves—were likely suffering, too.

Washington noted matter-of-factly that “We killed Mr. de Jumonville, the Commander of that Party.”

De Jumonville would become a martyr—and a persuasive tool for rallying the public against the British.

The French had dispatched de Jumonville on a diplomatic mission exactly like the kind Dinwiddie had envisioned for Washington: He was there to secure King Louis VI’s claim to the land and demand that the Virginians withdraw. De Jumonville was leading an ambassadorial delegation and never had any intention to fight. Had Washington attempted to engage peacefully, the French claimed, de Jumonville would have made that clear. Instead, a letter stating as much was later found on de Jumonville’s corpse. Retaliation was all but guaranteed.

At the age of twenty-two, Washington had committed a political misstep of global consequence. The British and the French were now formally engaged in a battle (known as the French and Indian War) for American land, forcing their allies in Austria, Germany, Prussia, Russia, Spain, and Sweden to take sides. The theater of war quickly spread into far-flung colonial holdings in the Americas, Africa, India, and even the Philippines. If the American Revolution had not taken place, Washington would probably be remembered today as the instigator of humanity’s first world war, one that lasted seven

...more

Washington’s disastrous performance on the frontier somehow turned out to be a social climber’s dream. Upon his return, he gave Dinwiddie his personal journal, which the governor recognized as a powerful tool for whipping up popular animus against the French; he had it published in newspapers throughout the colonies. It was a hit—a propaganda victory for the cause and a boost to the career of its author.

Martha was in a unique position for a young woman in the New World. At twenty-seven, the five-foot-tall widow was attractive in appearance, disposition, status, and family. She was petite, buxom, and had already given birth to two children—Jack, age four, and Patsy, age two—which signaled she was capable of bearing more for her future husband. Her father-in-law, half-brother-in-law, and late husband had died, the last without a will, leaving her one of the wealthiest women in Virginia—and free of meddling trustees. Martha was recognized as a so-called feme sole under English common law and had

...more

His first attempt to claim a seat in the House of Burgesses had failed, but this time George Fairfax and friends campaigned on his behalf, which in the eighteenth century meant plying voters with beer and spirits. And it worked. Washington would represent Frederick County during the 1758–1761 legislative session. No doubt rumors about his impending marriage helped his image as a well-to-do planter.

He’d managed to take a few prisoners when, in the failing light, a second contingent materialized out of nowhere. His troops panicked. Virginians were suddenly firing on Virginians, mistaking their fellow colonists for the enemy. Fourteen of Washington’s own men were dead before he managed to stop the bloodshed. And by the time he finally reached Fort Duquesne, the French had burned it to the ground and moved on.

He’d given up on the British military and, though he did not yet realize it, the British Empire. The French and Indian War set colonists, who had undergone their own cultural and social development in the New World, on the path to independence. They were learning that their goals and values differed from those of the crown, and that their concerns, even when voiced by the most ambitious, gifted, and loyal among them, fell on deaf ears.

Mount Vernon’s large enslaved community, of whom more than half originally belonged to the Custis estate, labored from sunup to sundown, six days a week, under the careful watch of overseers. Although estates like Mount Vernon are called “plantations,” it’s a word inflected with genteel romanticism. If we look at what actually occurred there, we see them for what they were: forced-labor camps.

Washington was quietly campaigning before there was anything to officially campaign for, and it worked. His charisma—that rarest of gifts—charmed and fascinated everyone around him. Delegates found him to be “discreet and virtuous,” and when he spoke they listened.

In Philadelphia, miraculously, the delegates reached a unanimous decision on June 15, 1775: They would raise an army, and George Washington would lead it.

It has been determined in Congress, that the whole Army raised for the defence of the American Cause shall be put under my care, and that it is necessary for me to proceed immediately to Boston to take upon me the Command of it. You may beleive me my dear Patcy, when I assure you, in the most solemn manner, that, so far from seeking this appointment I have used every endeavour in my power to avoid it, not only from my unwillingness to part with you and the Family, but from a consciousness of its being a trust too great for my Capacity. . . . it was utterly out of my power to refuse this

...more

Washington “lost more battles than any victorious general in modern history.”2 And yet, his performance as a military leader has been the subject of hundreds of biographies and thousands of books.

Washington’s insistence on being addressed by his title reminds us that he could be a brilliant tactician, but his strategic and intellectual victories off the battlefield have been totally overshadowed by his military triumphs during the Revolution. He won the war, but he didn’t do it with sheer force alone.

To pigeonhole him as a military leader is to underestimate how much the fledgling government needed Washington as a diplomat and political strategist. His ability to manage large-scale combat while also running spy rings and shadow and propaganda campaigns in enemy-occupied areas is a significant—and often overlooked—part of the Revolutionary War.

He even talked Congress into funding the New Jersey Journal, over which he could exert total editorial control, spreading stories about American good deeds and British evil. Benjamin Rush, a prominent physician who served briefly as surgeon general, described these newspapers as “equal to at least two regiments.”

At times, the crown had made peace treaties with the Indians that curtailed westward expansion, and the colonists saw themselves as the victims. In an attempt to reassure them, and with the full support of Congress, Washington undertook a campaign of genocide against the Six Nations, the northeast Iroquois confederacy.

Jay couldn’t get him what he was looking for—“a liquid which nothing but a counter liquor (rubbed over the paper afterwards) can make legible”—but his brother could.2 Sir James Jay, a physician in New York, had developed a “sympathetic stain” for secret correspondence. Washington called the invisible ink “medicine” and advised those he supplied with it to write “on the blank leaves of a pamphlet . . . a common pocket book, or on the blank leaves at each end of registers, almanacs, or any publication or book of small value.”

American currency would incriminate the spies if they were caught with it, and that was assuming they even wanted it; the new money was unstable, in large part because the British printed millions of counterfeit bills during the war. Ultimately Morris sent Washington forty-one Spanish dollars, two English crowns, ten shillings, and two sixpence.

Setauket was not known for patriot sympathy, but the British soon changed that. They took over everything—pubs, restaurants, boarding houses, and churches—and became an overwhelming, frightening burden. For some residents, the American cause was a fight for a quiet way of life. Their help became essential to the untrained intelligence operatives’ success.

All successful American military men were micromanaged, painstakingly audited, and occasionally court-martialed by the distrustful Continental Congress. The politicians feared that a celebrity general would emulate Oliver Cromwell and seize power. Washington, who’d learned to hold his tongue as an adult, bore these bureaucratic impositions well; Arnold never did.

Insult, alienation, and want of money made him easy prey for André, who passed messages between Arnold and British general Sir Henry Clinton. For what would now be around half a million dollars, Arnold agreed to hand over West Point—the patriots’ strategically key fortress on the Hudson River—to the British, along with Washington himself.20 Had Washington been captured, he would likely have been taken to London, tried, and hanged. Coupled with the loss of West Point, which Washington called “the most important Post in America,” Arnold’s betrayal might have ended the Revolution.

Arnold escaped punishment for his treason. He’d inconvenienced the patriots and damaged their morale, but he accomplished very little for the British.

The British and the Hessians brought smallpox with them when they arrived to quell the Revolution, and though Washington had been immune since contracting the disease in Barbados in 1751, he quickly learned that almost everyone around him was vulnerable.

The Virginia legislature, worried that inoculation would spread rather than contain the disease, made inoculation illegal. But the epidemic, which Washington called “this most dangerous enemy,” threatened to defeat the patriots; by 1776, 20 percent of his army had suffered or died from smallpox.

Variolation, a new technique, was risky; at best, it put soldiers out of commission for weeks at a time. Still, Washington decided to move ahead with compulsory mass inoculations. Smallpox-related fatalities of soldiers and recruits dropped by 17 percent as soon as inoculation was introduced; by the end of the war, it had reached 1 percent.

Martha was soon reunited with Washington in New York, and would ultimately remain by his side for half of the war.

When the British surrendered on October 19, 1781, the battlefield was littered with the rotting corpses of soldiers and their horses, which polluted the water and the air, spreading “camp fever,” or typhus. Jack quickly fell ill, but Washington wouldn’t have him treated in an overcrowded, malaria-infested makeshift hospital; he ordered Jack be spirited by carriage to his aunt’s home in Eltham, Virginia, thirty miles away,

I came here in time to see Mr. Custis breathe his last. [A]bout Eight o’clock yesterday Evening he expired. The deep and solemn distress of the Mother, and affliction of the Wife of this amiable young Man, requires every comfort in my power to afford them—the last rights of the deceased I must also see performed—these will take me three or four days; when I shall proceed with Mrs Washington and Mrs. Custis to Mount Vernon.

When Washington finally returned home to Mount Vernon two years after Yorktown, the mansion house was bigger, fuller, and poorer than ever.

It was a shocking turn of events for a man who had been so financially comfortable at the beginning of the war that he refused to take a salary.

Although he always spoke the language of democracy, his letters to Hamilton and other members of Congress made it hard to tell how ready he was to step down. These letters sometimes numbered five pages or more, touching on governmental concerns far outside a general’s purview. He didn’t like the Articles of Confederation, which had guided the United States through the latter years of the war. He worried about financial solvency, economic vitality, and the constant bickering and squabbling among state representatives. All of it signaled division and weakness rather than unity and strength.

It was an eye-opening ride. Washington had grown accustomed to the reverence he felt as he moved among his troops, but that paled in comparison to being America’s first real celebrity.

First, though, there was the small matter of his farewell address, which a congressional committee had been choreographing. There was no precedent, and no protocol. It was the first time in Western history that a general would be addressing his civilian superiors as he left military service.

Washington rose to deliver his speech. His voice was surprisingly ragged and his hands were shaking, but the words he spoke were consistent with everything he’d said before: He was unworthy of the role of general, but aspired to the cause, and succeeded because of Divine Providence and the men who served under him.

The country celebrated his voluntary resignation, and in London, subjects of the British crown marveled over “a Conduct so novel, so inconceivable to People, who, far from giving up powers they possess, are willing to convulse to the Empire to acquire more.” King George himself allegedly said, upon hearing of the plan, “If [Washington] does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.” America would spark an age of revolutions. When France experienced its own, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, he did not step down from power, but rather declared himself emperor. Years later, he would say, “They

...more

He believed that mules—a cross between a male donkey and a female horse—were the future of American farming, because they could do an equivalent amount of work to horses with less food and water.

Congress had waived postage fees on any letters addressed to Washington, which meant he was inundated with mail,

Washington himself was Mount Vernon’s most popular specimen. There was a steady stream of fans and opportunists who walked right up to the mansion house, hoping for a glimpse of or a word from the living legend.

But his contemporaries didn’t let up; they kept writing, asking for him to get involved with increasing urgency. “It is the general wish that you should attend,” Henry Knox wrote of the upcoming Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.14 If he could help the delegates address the deeply flawed Articles of Confederation and strengthen the central government, they might avoid an impending crisis.

All in all, it was a pleasant trip that concluded with consensus around the Constitution of the United States, with a preamble written by Morris.17 When the time came to sign it, Washington was the first; he was likely the first to depart Philadelphia, too. He did so satisfied that, with minimal interference, and at the expense of just a few weeks of neglecting private affairs, the country had been set on the right path. Now he could return to Mount Vernon for good. Unfortunately for Washington, he was the only one left with that impression. Alexander Hamilton, who had served as his

...more

The first presidential election in the United States was its least dramatic. There were no debates and no campaigns; when the Senate and the House of Representatives met for the first time on April 6, 1789, in New York to tally the votes, there were no surprises. George Washington appeared on every ballot and received sixty-nine electoral votes to secure the presidency.

when it came to the daunting roles they were about to assume, Washington was focused on big issues, like establishing enduring norms for his office and addressing foreign debt, whereas Adams was obsessed with essentially meaningless formalities, like the president’s title.

Billy Lee, the slave who was Washington’s manservant for the entirety of the war, was left behind when he could no longer keep up. After he was crippled due to injuries sustained in service to Washington, Lee was demoted to shoemaker.