More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

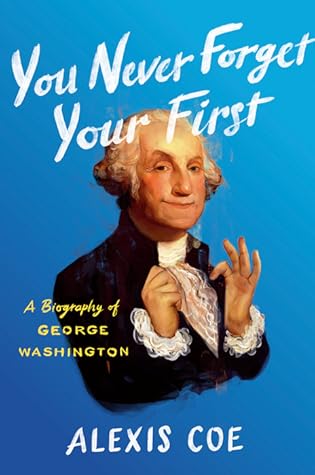

by

Alexis Coe

Read between

November 10 - November 11, 2022

If Washington had been a king, Americans waiting to celebrate him on the road to New York would have bowed, but since the country had evicted the monarchy, it was Washington who bowed to them. And they loved him for it.

“I Am not afraid to die, and therefore I can hear the worst,” Washington reportedly told his doctor, Samuel Bard, some seven weeks after his inauguration.16 According to Bard, he suffered from the cutaneous form of anthrax, which caused a carbuncle (an infection of the soft tissue) in his upper thigh. Washington did his best to avoid eighteenth-century medicine, which often left patients worse off than they began, but was in too much pain to object to Dr. Bard’s insistence:

Washington was bedridden for six weeks, during which time he wrote no letters and received few guests. A slow recovery followed,

He eventually recovered, only to be taken ill again and again during his presidency; there was a repeat abscess in his thigh, and later, his cheek; he experienced regular fevers, inflammation of the eye, and back strains; he fell off a horse and had to use a crutch to move around. In the spring of 1790, during a flu outbreak in New York, he became infected. Although he experienced a high fever, delirium, and bloody sputum, Martha wrote that he “seemed less concerned himself as to the event than perhaps almost any other person in the United States.”

Even if Washington had managed to procure hemlock for his mother when she first asked for it, it would have made no difference. Betty’s letter arrived in July, and by August 10, 1789, Mary had stopped speaking. She died fifteen days later.

Washington, by then busy with the presidency, replied to Betty with a quick note of comfort and advice on estate proceedings; he did not share his feelings past remarking the obvious.

The Continental Congress was wholly responsible for the conflict; it had effectively stolen large swaths of indigenous land, claiming that the Indians had forfeited their right to it by supporting the British during the Revolution. (In reality, only a handful of tribes had actually done so.)

The Creeks, who had made significant land cessations in 1783, 1785, and 1786, were no longer honoring the treaties they’d signed.

Washington sided with the settlers, of course, but believed the solution was to send missionaries to teach Indians, who believed in using land in ways that left little lasting impact, to farm and raise animals.

going in to the negotiations, he had to rely solely on information from Knox, whose jurisdiction included Indian affairs. (The peace treaty eventually drawn up with the southern Indians marked the official beginning of the tortured—if not outright genocidal—relations between tribal nations and the federal government.)

America was born with enough wartime debt to crush it to death. The government owed forty million dollars to its own citizens, who had loaned it money, and twenty-five million to individuals around the world. France, now in the throes of its own revolution, was the United States’ main overseas creditor, and a sensitive one at that. It was already feeling unappreciated by the United States, and delayed repayment would only aggravate that feeling.

the Washingtons would use people they enslaved—even though Philadelphia had recently passed the Gradual Abolition Act, which freed any slave who reached the age of twenty-eight or lived in the city for six months.

Attorney General Edmund Randolph came to Martha with a warning. While it was well known that the slaves of congressmen, foreign ministers, and consuls were exempt from the Gradual Abolition Act—those officials could keep their slaves as property as long as they stayed in town—it seems Randolph’s slaves were the first to figure out that the executive branch’s slaves were not exempt. When they discovered the truth, they informed the attorney general they intended to claim their freedom. Randolph suggested that Martha send her slaves away to avoid the same fate; even a short trip would buy the

...more

“[T]he idea of freedom might be too great a temptation for them to resist,” Washington wrote to Lear; it certainly was at Mount Vernon, where slaves attempted to flee with some regularity. “I do not think they would be benefitted by the change,” he added. Their owner certainly wouldn’t.

Jefferson and Madison, who were ideological allies, quietly funded Philip Freneau’s National Gazette, which criticized all of Washington’s policies and attacked Federalist supporters; he was, at least in the first term, far too popular with the people to assault directly. Just as they had blamed Parliament for misleading the king, they now blamed Washington’s seemingly favorite adviser, Hamilton, for misleading the president. Hamilton was already promoting—and perhaps backing—John Fenno’s Gazette of the United States, a pro-administration paper; he sometimes wrote for it under the name “An

...more

Though Washington was sympathetic to the Federalists, he remains the only president who never claimed a political affiliation while in office.

By 1792, the first president had set up a functioning executive branch and established conventions for future presidents to either follow or reform. He had overseen the passage of the Bill of Rights; appointed all ten Supreme Court justices, thirty-eight federal judges, and twenty-eight district judges; declared the first Thanksgiving; welcomed Rhode Island, Vermont, and Kentucky into the union; formed armies under federal regulation; and signed the Naturalization Act, which granted citizenship to any free white person who had been in the country for at least two years.30 There were banks and

...more

Washington was inclined to ignore the treaty and declare neutrality; he felt that the country shouldn’t be bound by an agreement that the Continental Congress, which no longer existed, had made with the French crown, which also no longer existed.

But Washington wasn’t just being careful. He was being savvy. If America remained neutral, it could sell goods to both nations.

Jefferson did emerge with one diplomatic win: Washington agreed to receive Edmond-Charles Genêt, the first ambassador from the French Republic. But when Genêt arrived in the spring of 1793, he didn’t go straight to Philadelphia, as he should have, to pay his respects to the president. Instead, the young redheaded ambassador began a monthlong anti-neutrality tour from Charleston, South Carolina, to New York. He urged Americans to openly defy Washington—whom he described as “a man very different from the character emblazoned in history”—by pressuring Congress to declare support for France,

...more

Right after Washington refused to use military force against a foreign nation, he turned it on his own people in what would ultimately be the biggest overreaction of his life. In 1794, the government was having trouble collecting an excise tax—a part of Hamilton’s plan to pay back foreign debt—from distillers in the Kentucky and western Pennsylvania backcountry.

He saw these local attacks as a direct challenge to legitimate federal authority and was determined to quash the protest and have its participants tried for treason. But according to the Constitution, the commander in chief could send in troops only at the request of state officials, and Pennsylvania governor Thomas Mifflin wasn’t ready to take that step.

In an extraordinary showing of executive overreach, he sidestepped both Mifflin and the Constitution, securing a judicial writ from Associate Justice James Wilson, called out state militia for federal service, and hired a tailor to make him a uniform modeled after the one he’d worn in the war.12

He became the first and only president to take up arms against his own citizens,

The press was stunned by Washington’s imprudence: The man famous for his self-control and judiciousness had neglected to consider whether military action was warranted. Couldn’t he have simply threatened the poor civilians into submission—or, better yet, actually talked to them?

With some effort, the troops arrested one hundred and fifty whiskey rebels. But without much evidence, and with few people willing to testify, only two men, John Mitchell and Philip Wiegel, were found guilty of treason. Although Washington bragged about the peaceful resolution, he must have felt embarrassed about the situation, or at least the reception his overreaction had received; he used a presidential pardon for the first time in history, and let the men go.

Congress, which had been quietly questioning whether the Constitution even allowed a president to declare neutrality on his own—after all, he could not unilaterally declare war—was on edge.

the Republicans in the House, led by Madison, refused to let the Jay Treaty go, and a standoff ensued. In the spring of 1796, they demanded that the president share the diplomatic instructions Jay had received. Washington refused, asserting for the first time what would become known as executive privilege.

“Your conduct has been represented as derogating,” Washington wrote on July 6, 1796, his patience depleted. Jefferson, or at the very least his cohorts, had made him out to be Hamilton’s puppet, “a person under a dangerous influence.”5 He sent his last letter to Jefferson the next month; it was an obligatory note, no more than five sentences long, appended to some papers he’d promised to forward.6 They never spoke again.

Washington always emphasized that emancipation be gradual; one could argue that this was to acclimate everyone to the notion, but it would, most importantly, lessen the financial blow to slave owners. Still, he did nothing to address the issue while he was in office.

Adams, the first (and only) president who openly identified with the Federalists, wanted to muster an army in case hostilities broke out, and turned to sixty-six-year-old Washington, who had left the Continental Army fifteen years earlier, to lead it.14 “We must have your Name, if you, in any case will permit Us to Use it,” Adams pleaded in June 1798.

Washington agreed, as long as he could remain at Mount Vernon until “the army is in a situation to require my presence, or it becomes indispensible by the urgency of circumstances.”

Ultimately, though, Adams opted for a diplomatic solution. The conflict became known as the Quasi-War, or the Half War, or the Undeclared War.

The document, which includes a painstaking inventory of his worldly possessions, reveals him to be one of the richest men in America. He wasn’t lying when he had claimed to be cash poor—though there always seemed to be money for finery, or to hire slave hunters to catch Hercules and Ona Judge—but he wasn’t exactly telling the truth, either.

In his will he stipulated that his hundred and twenty-three slaves should be freed—after Martha had her use of them, and the income they would generate.

At 3 p.m. on December 18, 1799, four days after Washington’s death, a schooner on the Potomac fired off a twenty-one-gun salute. On land, Virginia Cavalry led a funeral procession to the beating of drums; up at the front, two of the general’s slaves, Cyrus and Wilson, led his riderless horse.

Washington’s will had been circulated in pamphlet form. Some of his slaves had decided to immediately emancipate themselves and fled Mount Vernon, while the rest watched her closely, knowing that her death meant their freedom. “She did not feel as tho her Life was safe in their Hands,” Abigail Adams explained to her sister, Mary Adams.

In her own will, the slaves she controlled, whom she could have freed, she left to her family. It was not, then, morality that drove Martha to, on December 15, 1800, sign a deed of manumission, freeing all of her late husband’s slaves. It was self-preservation.