More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

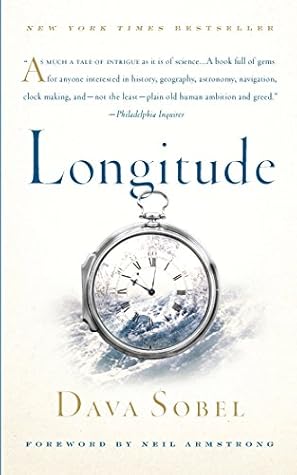

by

Dava Sobel

Read between

December 29, 2018 - January 17, 2019

The experience imparted a vivid memory: Clocks were important.

Each element was impeccably crafted, giving the impression of being created by a jeweler rather than by a carpenter.

English clockmaker John Harrison, a mechanical genius who pioneered the science of portable precision timekeeping, devoted his life to this quest. He accomplished what Newton had feared was impossible: He invented a clock that would carry the true time from the home port, like an eternal flame, to any remote corner of the world.

Roemer used the departures from predicted eclipse times to measure the speed of light for the first time in 1676. (He slightly underestimated the accepted modern value of 300,000 kilometers per second.)

(Today, scientists assert that the moon is not speeding up; rather, the Earth’s rotation is slowing down, braked by tidal friction, but Halley was correct in noting a relative change.)

It took John Harrison nineteen years to build H-3.

A novel antifriction device that Harrison developed for H-3 also survives to the present day—in the caged ball bearings that smooth the operation of almost every machine with moving parts now in use.

Indeed, some modern horologists claim that Harrison’s work facilitated England’s mastery over the oceans, and thereby led to the creation of the British Empire—for it was by dint of the chronometer that Britannia ruled the waves.

Then it ascends to its summit and waits another two minutes. Mobs of school groups and self-conscious adults find themselves craning their necks, staring at this target, which resembles nothing so much as an antiquated diving bell. It’s a far cry, indeed, from the glitz of Times Square on New Year’s Eve.

I finished this, with a gale lashing the rain on to the windows of my garret, about 4 P.M. on February 1st, 1933—and five minutes later No. 1 had begun to go again for the first time since June 17th, 1767: an interval of 165 years.”