More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Dava Sobel

The zero-degree parallel of latitude is fixed by the laws of nature, while the zero-degree meridian of longitude shifts like the sands of time.

Every day at sea, when the navigator resets his ship’s clock to local noon when the sun reaches its highest point in the sky, and then consults the home-port clock, every hour’s discrepancy between them translates into another fifteen degrees of longitude.

One degree of longitude equals four minutes of time the world over, but in terms of distance, one degree shrinks from sixty-eight miles at the Equator to virtually nothing at the poles.

In consequence, untold numbers of sailors died when their destinations suddenly loomed out of the sea and took them by surprise. In a single such accident, on October 22, 1707, at the Scilly Isles near the southwestern tip of England, four homebound British warships ran aground and nearly two thousand men lost their lives.

The British Parliament, in its famed Longitude Act of 1714, set the highest bounty of all, naming a prize equal to a king’s ransom (several million dollars in today’s currency) for a “Practicable and Useful” means of determining longitude.

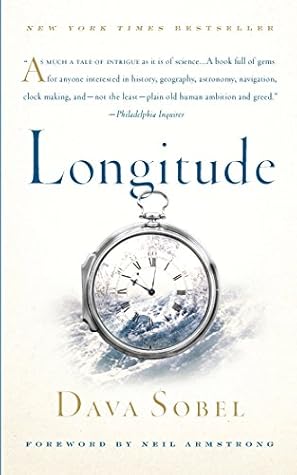

English clockmaker John Harrison, a mechanical genius who pioneered the science of portable precision timekeeping, devoted his life to this quest. He accomplished what Newton had feared was impossible: He invented a clock that would carry the true time from the home port, like an eternal flame, to any remote corner of the world.

Galileo’s method for finding longitude at last became generally accepted after 1650—but only on land. Surveyors and cartographers used Galileo’s technique to redraw the world.

Roemer used the departures from predicted eclipse times to measure the speed of light for the first time in 1676. (He slightly underestimated the accepted modern value of 300,000 kilometers per second.)

he applied the word cell to describe the tiny chambers he discerned in living forms.

“when the Forestaff was most in use, there was not one Old Master of a Ship amongst Twenty, but what a Blind in one Eye by daily staring in the Sun to find his Way.” This was true enough. When English navigator and explorer John Davis introduced the backstaff in 1595, sailors immediately hailed it as a great improvement over the old cross-staff, or Jacob’s staff. The original sighting sticks had required them to measure the height of the sun above the horizon by looking directly into its glare, with only scant eye protection afforded by the darkened bits of glass on the instruments’ sighting

...more

the clock itself remains. Its movement and dial—signed, dated fossils from that formative period—now occupy an exhibit case at The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers’ one-room museum at Guildhall in London.

Harrison further guaranteed the wheel teeth their enduring structure by selecting the oak from fast-growing trees, whose growth rings formed widely spaced ripples in the trunks. Such trees yield lumber with a wide grain and great might, due to the high percentage of new wood. (Under microscopic examination, growth rings resemble a honeycomb with hollows, while the new wood between the rings seems solid.)

Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler, who had reduced the relative movements of the sun, the Earth, and the moon to a series of elegant equations.

was John Jefferys, a freeman with The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. In 1753, Jefferys made Harrison a pocket watch for his personal use. He obviously followed Harrison’s design specifications, for Jefferys fitted the watch with a tiny bi-metallic strip to keep it beating true, come heat or cold.

Mudge won lasting acclaim for his lever escapement, which appeared in nearly all mechanical wrist- and pocket watches manufactured through the middle of the twentieth century, including the famous Ingersoll dollar watch, the original Mickey Mouse watch, and the early Timex watches.