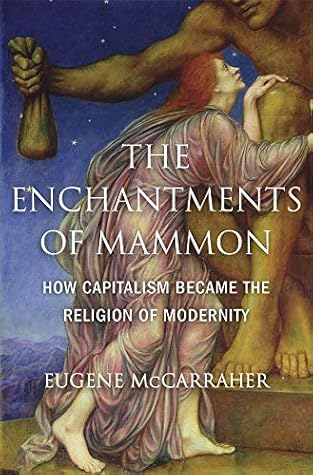

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The world is charged with the grandeur of God. It will flame out, like shining from shook foil; It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod? Generations have trod, have trod, have trod; And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

For the four decades before the financial crisis unfolded in the fall of 2008, capitalism’s lavish indifference to piety was a major selling point. In the fleshpots of American suburbia, where the armada of SUVs ferry the heavily indebted through the consumer republic, the spectacular reign of money seemed well nigh ubiquitous and irreversible.

capitalism offered the sale of commodities, not the dutiful worship of relics; the fulfillment of the self, not subordination to the past; the romance of the present and the promise of the future, not a vale of tears and a hope

Capitalism’s most unlikely celebrant, Marx observed how the market, far from being a bastion of conservatism, dissolves “all fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices.”

History’s assassin of enchantment, capitalism “drowns the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervor … in the icy water of egotistical calculation.”

To journalist Naomi Klein, the neoliberal economics of the past forty years amounts to a veritable creed, “the contemporary religion of unfettered free markets.” Indeed, “corporate business has always had a deep New Age streak,” she observes, with branding as the most advanced form of “corporate transcendence.” The Nike swoosh, the Starbucks siren, and other trademarks are neoliberal totems of enchantment.

Journalist Barbara Ehrenreich discovers that, despite its reputation for a ruthless focus on the bottom line, corporate business is “shot through with magical thinking,” inspired and mesmerized by a burgeoning portfolio of New Age quackery and bunkum. Evangelicals refer to Jesus Christ as their “CEO” or personal investment advisor, while management writers cull from Lao-tzu, Buddha, Confucius, and Carl Jung. Counting out “seven habits” or “four competencies” or “sixty-seven principles of success,” business advice books can be as comically arcane as end-times prophecy, the oracles of

...more

“Material things are shot through with enchantment,” New York Times columnist David Brooks informs us. Suburban acquisitiveness stems from a “sacramental longing,” Brooks believes, a desire to enter “a magical re...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Contemporary writers are not the first to note the persistence of enchantment in capitalist societies. Reflecting on the misery of industrial England in the 1840s, Thomas Carlyle detected the presence of “invisible Enchantments” that bewitched the “plethoric wealth” that had “yet made nobody rich.”

Owners and workers walked “spell-bound” in the clutches of a “horrid enchantment,” beguiled by some power that lurked in the factories and inhabited the things they produced. Carlyle traced this sorcery to “the Gospel of Mammonism,” the good news that money possessed and bestowed a trove of “miraculous facilities.”

“is like the sorcerer, who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world he has called up by his spells.”

Later, in the first volume of Capital, Marx included a seminal passage on “the fetishism of commodities,” the attribution of human or supernatural qualities to manufactured objects.

Four decades later, after marking the epoch of disenchantment, Weber mused that “many old gods ascend from their graves,” resurrected as the “laws” of the ma...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Walter Benjamin suggested almost a century ago that capitalism is a religion as well, a “cult” with its own ontology, morals, and ritual practices whose “spirit … speaks from the ornamentation of banknotes.”6 I take this as a point of departure and argue that capitalism is a form of enchantment—perhaps better, a misenchantment, a parody or perversion of our longing for a sacramental way of being in the world.

What Carlyle dubbed “the Gospel of Mammonism” is the meretricious ontology of capital, in which everything receives its value—and even its very existence—through the empty animism of money. It proclaims that capital is the mana or pneuma or soul or elan vital of the world, replacing the older enlivening spirits with one that is more real, energetic, and productive.

Protestant theology and capitalism played crucial roles in Weber’s tale of disenchantment. Rejecting the “foolish and doctrinaire” idea of a direct causal link between the two, Weber argued that the connection inhered both in the “elective affinities” of Protestant theology and capitalist enterprise and in the “psychological drives” for accumulation sanctioned by the new religious doctrines. The “elective affinities” of Protestantism and capitalism originated in the repudiation of Catholic sacramentalism—a Christianized form, he implied, of the earlier enchanted universe, a cultic ensemble of

...more

Lacking the assurance of salvation provided by Catholic sacramental rituals, the Calvinist allayed the inevitable anxiety through “tireless labor in a calling.” So the “spirit of capitalism” was not, Weber argued, just another term for greed; it was the rationalized accumulation of wealth, undertaken, Calvinists convinced themselves, for the sake of God’s glory and majesty. In the process, Calvinist capitalists achieved a “sanctification of worldly activity” and cultivated an “innerworldly asceticism,” which, once loosened from its theological moorings, became the classic trinity of bourgeois

...more

In our incorrigibly ironic era of postmodernism, the venerable questions of meaning and destiny are sloughed off as unreal and coercive “metanarrative”; even revolutionary hope—another grasp at transcendence—yields to the conquest of cool, the imperium of a hip plutocracy.

Marx referred to “the divine power of money” and its status as “the god among commodities.”

As the realm of the commodity widens, money not only purchases everything; it also seems to bring things into being from nothing, performing all manner of astonishing feats of moral and metaphysical alchemy.

Money can buy you love: as the young Marx mused in an early reflection on “the power of money in bourgeois society,” money enables its possessor to say “I am ugly, but I can buy for myself the most beautiful of women. Therefore I am not ugly, for ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“the riddle of history is not in Reason, but in Desire; not in labor, but in love.”)18 Capitalism is one such desire for communion, a predatory and misshapen love of the world. (Capitalism is a love story.)

have relied on a sizable body of historical literature on the symbolic universe of capitalism. Much of this work suggests that capitalist cultural authority cannot be fully understood without regard to the psychic, moral, and spiritual longings inscribed in the imagery of business culture.

Responding to this crisis of moral legitimacy, public relations departments conjured, Marchand argued, a “corporate soul,” an image of the corporation as a friendly neighborhood behemoth solely interested in community service.

am not one of those churlish reactionary radicals who see nothing in capitalist modernity but one long, unrelieved nightmare of greed, brutality, and desiccating rationalization. The technological achievements of capitalism have surely improved the social and material conditions of billions of people; as none other than Marx asked in the Communist Manifesto, what earlier time “had even a presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labor?” Still—and this needs to be reiterated at a time of wavering but nonetheless ascendant capitalist triumphalism—these improvements

...more

Moreover, it is essential to remember that, as Benjamin observed, every document of civilization is also a document of barbarism; during the tragically dialectical epoch of class struggle, all human achievement is tainted by oppression.

(Even Marx succumbed to it.) Yet they did not call for the restoration of earlier social orders, nor did they believe that hammers and hoes would exhaust the technical possibilities of a world after capitalism.

Their example suggests not that we should resurrect the past, but that we need to revisit what we mean by “progress,”

rather than rail against consumerism, I affirm John Ruskin’s magnificent adage that “there is no wealth but life,” as well as his distinction between “wealth”—that which helps produce “full-breathed, bright-eyed, and happy-hearted human creatures”—and “illth”—that which causes “devastation and trouble in all directions.”

Through much of the twentieth century, the corporation presided over the Fordist endeavor to build a heavenly city of business, a celestial metropolis of capital achieved through the mechanization of production and communion. By the early twenty-first century, capitalism has reached its highest meridian of enchantment in the neoliberal deification of “the Market.”

Vida Dutton Scudder,

As Henry Miller realized, “the earth is a Paradise. We don’t have to make it a Paradise—it is one. We have only to make ourselves fit to inhabit it.”

As the master science of desire in advanced capitalist nations, economics and its acolytes define the parameters of our moral and political imaginations, patrolling the boundaries of possibility and censoring any more generous conception of human affairs.

Under the regime of neoliberalism, it has been the chief weapon in the arsenal of what David Graeber has characterized as “a war on the imagination,” a relentless assault on our capacity to envision an end to the despotism of money.

Insistent, in Margaret Thatcher’s ominous ukase, that “there is no alternative” to capitalism, our corporate plutocracy has been busy imposing its own beatific vision on the world: the empire of capital, with an imperial aristocracy enriched by the labor of a fearf...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Every avenue of escape from accumulation and wage servitude must be closed, or better yet, rendered inconceivable; any map of the world that includes utopia ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The grotesque ontology of scarcity and money, the tawdry humanism of acquisitiveness and conflict, the reduction of rationality to the mercenary principles of pecuniary reason—this ensemble of falsehoods that comprise the foundation of economics must be resisted and supplanted.

As a legion of anthropologists and historians have repeatedly demonstrated, economics, in Graeber’s forthright dismissal, has “little to do with anything we observe when we examine how economic life is actually conducted.” From its historically illiterate “myth of barter” to its shabby and degrading claims about human nature, economics is not just a dismal but a fundamentally fraudulent science

The Romantic antipathy to capitalism, mechanization, and disenchantment stemmed not from a facile and nostalgic desire to return to the past, but from a view that much of what passed for “progress” was in fact inimical to human flourishing: a specious productivity that required the acceptance of venality, injustice, and despoliation; a technological and organizational efficiency that entailed the industrialization of human beings; and the primacy of the production of goods over the cultivation and nurturance of men and women. This train of iniquities followed inevitably from the chauvinism of

...more

We will not be saved by our money, our weapons, or our technological virtuosity; we might be rescued by the joyful and unprofitable pursuits of love, beauty, and contemplation. No doubt this will all seem foolish to the shamans and magicians of pecuniary enchantment.

Gerard Manley Hopkins

Since God dwells among us, the universe is radiant, “like shining from shook foil.” Yet, oblivious to God’s enchantment of the earth, “generations have trod, have trod,” and as a result of our industrious inattention, “all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil.”

In the summer of 1871, Hopkins had written to a friend about the bloody suppression of the Paris Commune. “In a manner I am a Communist,” he confessed, for the ideal of communism is “nobler than that professed by any secular statesman I know of.” “Besides,” he added curtly, “it is just.” “It is a dreadful thing,” he continued, “for the greatest and most necessary part of a very rich nation to live a hard life without dignity, knowledge, comforts, delight, or hopes in the midst of plenty—which plenty they make.”

Though Hopkins’s “manner” of being a communist would surely have failed any test imposed by Marx and his comrades in the First International, Hopkins was certain that reverence for God’s grandeur demanded the end of capitalist iniquity.

English Protestants espoused a systematic theology of the divine right of capitalist property.

Epitomized by Gerard Winstanley and the Diggers, a sacramental, communist materialism prefigured the modern, secular left.

Ricardo. For the clerics of evangelical enchantment, God had manufactured the capitalist cosmology of property, market, and enterprise, with scarcity and struggle as His paternal inducements to labor, innovation, and riches. Marveling at the dreadful beauty of a strife commanded by the Creator, English evangelicals preached and imposed the gospel of capitalist freedom.

Karl Marx, for instance, detected the persistence of the spirits in capitalist modernity. From the oldest fabrication of gods and spirits to the superstition of “commodity fetishism,” human beings had projected their own inherent powers onto illusory but oppressive beings.

Even the culture of “Carnival” held enchanted, eschatological meaning. At its pinnacle in the Feast of Fools—when lords and serfs changed places for a day, while laity mocked priests and bishops—Carnival included the temporary, utopian erasure of social hierarchies. Carnival was a glimpse of “the beatific vision” in fleshly, joyful plenitude; for a day, the gates of heaven opened, the future paid a visit to the present, and carnal splendor could provide a robust foretaste of the impending kingdom of God.

“Every other sin has its periods of remission,” warned Caesarius of Heisterbach, another thirteenth-century moralist, but “usury never rests from sin. Though its master be asleep, it never sleeps, but always grows and climbs.”