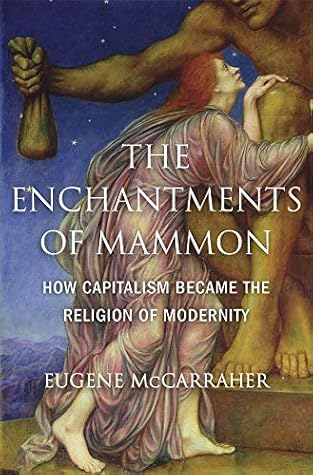

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

the lashes of adversity and competition would compel us into moral and material improvement.

Malthus argued that moral evils and natural calamities were “absolutely necessary to the production of moral excellence … instruments employed by the Deity” to spur industriousness and ingenuity.

Malthus’s insistence on the goodness of disaster rested on a toilsome, penurious sacramentality, an ontology of dearth and meanness designed by an omnipotent but skinflint deity. Life is “the mighty process of God,” he insisted, “a process necessary to awaken inert, chaotic matter into spirit.”

“The finger of God is, indeed, visible in every blade of grass that we see,” and among the “animating touches of the Divinity” is the salutary character of evil. “Evil exists in the world not to create despair but activity.” (If it failed to spur industry, then, Malthus wrote in the 1826 edition, “we should facilitate, instead of foolishly and vainly endeavoring...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Senior—first professor of political economy at Oxford, and a protégé of Whately’s—told students in 1830 that God and nature “decreed that the road to good shall be through evil—that no improvement shall take place in which the gen...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

So rather than look to reform or revolution to end their miserable condition, evangelicals such as Cobden advised workers that they should abide by “the principle of competition which God has set up in...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

By the 1840s, many workers had been acquainted with that “principle of competition” through subjection to the industrial division of labor. Misenchanted and driven by the same imperatives that propelled earlier agrarian “improvers,” Victorian manufacturers and merchants patented industrial forms of enclosure.

The transformation of skilled workers into factory hands—the “proletarianization” of craft, a process every bit as coercive as the eviction of peasants from the commons—was essential to the introduction of industrial technology. As Andrew Ure acknowledged in The Philosophy of Manufactures (1835), “skilled labour gets progressively superseded, and will eventually, be replaced by mere onlookers of machines.”

To design the technical and moral artillery for its warfare against the workers, capital enlisted the skills of a new and specialized breed of improvers: managers, scientists, engineers, and consultants, the vanguard of industrial progress.

Christian language of sacramentality; and

But Ure’s geological work was not merely another case study in fundamentalist folly. The same evangelical faith that inspired his geology also galvanized his managerial thought, for Ure considered his “philosophy of manufactures” a vindication of God’s mechanical ways to human beings. An apparently mechanistic ontology underlay both Ure’s promotion of industrial technology and his case for managerial prerogative. God’s universe was a vast machine composed of moral and material parts. Thus, in The Philosophy of Manufactures, Ure could admonish the wise manufacturer to “organize his moral

...more

With the Luddite uprisings of the 1810s still terrifyingly fresh in his memory, and with Chartist agitation for the suffrage gathering strength among the working class, Ure looked to industrial and technical means to quell proletarian disruption. At the bidding of Minerva—the Roman goddess of crafts and commerce—an “Iron Man, as the operatives fitly call it, sprung out of the hands of our modern Prometheus.” By subjecting workers to the political fatigue induced by factory regimentation, this mechanical golem would “restore order among the industrious classes” and “strangle the Hydra of

...more

Minerva.

To evangelical economists, the Almighty’s didactic malevolence was evident.

The starvation that racked the Irish people was “the judgment of God” on “the selfish, perverse, and turbulent character” of the Irish people, in the words of Sir Charles Trevelyan, prominent evangelical and chief administrator of famine relief; it was “the direct stroke of an all-wise and all-merciful Providence.” (Though some economists grumbled that Providence had botched the job: Senior complained that a million deaths “would scarcely be enough to do much good.”)

God’s painful but ultimately beauteous providence had a benevolent purpose: shoving the indigent Irish along the Calvary road of industrial modernization. Followed with Malthusian piety, evangelical economics played a central role in prolonging and deepening the catastrophe in Ireland.

Evangelical capitalists and their fawning clerisy induced the disease to which they offered a paltry, sanctimonious remedy. John Ruskin—who “unconverted” from his parents’ evangelical faith—would later excoriate this heartless sentimentality. “You knock a man into a ditch, and then you tell him to remain content in ‘the position in which Providence has placed him,’ ” he sneered in The Crown of Wild Olive (1866). “That’s modern Christianity.”

In The Protestant Ethic, he predicted the reign of professional and managerial experts, “specialists without spirit, hedonists without heart.” The permanently disenchanted world would be a wasteland of mass-produced tedium and vanity, a “monstrous development” of “ossification, dressed up with a kind of desperate self-importance.”

“The more man puts into God, the less he retains in himself,” Marx asserted in the then-unpublished but now renowned “economic and philosophic manuscripts” of 1844.

Yet if religion was the “opium of the people,” as he had written in an essay published earlier that year, it was also “the soul of soulless conditions,” an “illusory happiness,” the “halo” for a “vale of tears.”

Marx admonished the enlightened radicals of his day that it was not enough simply to hector the oppressed about the opiate illusions of religion; they must mobilize the wretched to reclaim the m...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condi...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Again, religion would be overcome through political struggle and material development, not the secularist homilies of the intelligentsia.

With wage-laborers divorced both from the means of production and from their own products, capitalist alienation took a fetishistic turn, an ascription of life to objects produced by none other than the workers themselves. “The life which [the worker] has given to the object sets itself against him as an alien and hostile force,” he mused. “If the product of labor does not belong to the worker, but confronts him as an alien power, this can only be because it belongs to a man other than the worker.”

But after drowning traditional religious faith in the vat of pecuniary reason, money became “the almighty being,” the “truly creative power,” the de facto ontological basis of reality in capitalist civilization.

As the realm of the commodity widens, money not only purchases everything; like the God of Genesis, it also brings things into being from nothing

“If I have the vocation for study but no money for it, I have no vocation for study—that is, no effective, no true vocation. On the other hand, if I have really no vocation for study but have the will and ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

As the metaphysical common sense of market society, it defines and even bestows all manner of qualities. “I am stupid, but money is the real mind of all things a...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Money can even buy you love: “I am ugly, but I can buy for myself the most beautiful of women. Therefore I am not ugly, for the effect of ugliness—it...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Money confers powers once believed to belong to shamans, priests, and gods.

in Capital, Marx portrayed the industrial apparatus as “a mechanical monster whose body fills whole factories, and whose demon power, at first veiled under the slow and measured motion of his giant limbs, at length breaks out into the fast and furious whirl of his countless working organs.” This was not mere melodramatic rhetoric, for it conveyed Marx’s central contention about the nature of modern machinery and industry: that its “demon power” was, in the end, the stolen and disfigured productive potency of the workers themselves.

Later Marxists would complement the master’s insights into technology with attention to those who directly wield the “demon power”—the “professional-managerial class” spawned in the division of mental from manual labor.

Enveloped in the aura of science and expertise, managers and technicians conjured what Alfred Sohn-Rethel has called “managerial fetishism,” the belief that specialists possess recondite, almost esoteric knowl...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

But as with the phantasmagorical figures of religion and commodity fetishism, the source both of technological enchantment and of managerial fetishism lay in the expropriation from workers of their own inherent powers.

“It is an enchanted, perverted, topsy-turvy world … this religion of everyday life,” as Marx observed in the third volume of Capital.

Yet Marx and Engels themselves provided ample reason to doubt that what they called the “pre-history” of the species would end in a Götterdämmerung of disenchantment. It was never clear that the reduction of the workers to industrial servitude would result in revolution, as money, that “god among commodities,” exercised a potent and increasingly untrammeled authority in capitalist society. If all traditional sources of moral and ontological truth were pulverized in the course of capitalist development—if indeed, as they proclaimed in the Manifesto, “all that is solid melts into air, all that

...more

With sufficient technical and political ingenuity—mass production, consumer culture, the welfare and regulatory policies of modern liberalism and social democracy—the sacramental sorcery of the system’s fetishism could retard, assimilate, or even extinguish the growth of revolutionary consciousness.

Abandoning his earlier hope that the realms of work and play could intermingle, Marx held in the Grundrisse that “labor cannot become play”; work and free time were now conceived as strictly demarcated spheres of human life.

The atrophy of this ideal stemmed, in part, from Marx’s contention that machinery’s use-value for producing goods would remain after the revolutionary supersession of capital—a use-value that he himself demonstrated lay in the systematic subordination of workers. Here Marx regressed into liberal, technocratic bromides about the “neutrality” of technology;

but if indeed, as Marx himself had asserted, capitalists reshaped labor and machinery “in a form adequate to capital,” then socialists would inherit a technological and organizational apparatus designed expressly for ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

neither Marx nor Engels explained how a technics so thoroughly imbued with the sensibility of domination could be made democratic.

While industrial despotism was precisely what was supposed to be “revolutionized from top to bottom,”

Engels employed the language of despotism itself to describe the process of revolution. As he insisted quite sternly in his 1872 essay “On Authority”—a volley in his ongoing battle with anarchists—machinery “is much more despotic ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Because of the intricacy and precision of its mechanical elements and the vast interdependence it created, modern machinery, Engels admonished the anarchists, both exercised a “veritable despotism independent of all social organization” and underscored “the necessity of a...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Engels’ authoritarian rhetoric was prima facie evidence that the “revolution” envisioned was not nearly profound enough, as the “despotism” entailed by modern industry signaled the persistence of alienation—the precondition for fetishism.

The work ethic of communism, as Marx described it, could seem more exacting than anything envisioned in the antiquated morality of Puritanism. As he declared in the “Critique of the Gotha Program” (1875), in communist society labor will become

“not only a means of life but life’s prime want.”

also enforces the need to incessantly strive,

Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer were right when they later surmised that Marx wanted to turn the world into a factory, and that his vision of communism resembled “a gigantic joint-stock company for the exploitation of nature.”31 Aside from the extensive ecological damage inflicted by this promethean tempest, the fetish of productivity would appear to intensify the exploitation of workers—indeed, by none other than themselves. Under Marx’s auspices, Prometheus morphed into a technically proficient and always preoccupied Sisyphus, ever in search of new mountains and boulders to exhibit his

...more

Whatever virtues and beauties the past may have possessed, they must not impede the forward march of progress. Revolutionaries must “let the dead bury their dead.”