More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

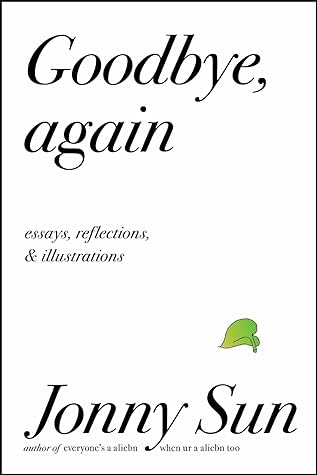

by

Jonny Sun

Read between

April 20 - April 25, 2021

For my parents, who I have said goodbye to more than anyone else, which I suppose is in itself its own kind of blessing.

I had felt burned out from the relentlessness of the world, and from my attempts to retreat into “productiveness”—to spend all my time focused on something that I knew would bring me stress but in exchange would give me some semblance or illusion of control—in the hopes that I could find some solace in the distractions of always having something I should be working on.

All of that led to even deeper burnouts, which led to deeper depressive episodes, which ultimately led to a bargain I made with myself that said I needed to start taking better care of myself if I were to continue to survive.

There was this constant voice in my head telling me that my own rest and recovery and catharsis were not valuable to anybody (or perhaps more honestly, I thought they were not valuable to myself) unless I could have something to show for it, unless I could share it.

You move into an empty space feeling uncertain about it, and slowly, you let the space hold onto that uncertainty so you don’t have to. And when you leave, you leave it again as an empty space, taking back the uncertainty that you were storing in it. It ends with an empty room, the same way as it began, although you’ve changed in all the time in between.

You can’t outrun sadness because sadness is already everywhere. Sadness isn’t the visitor, you are.

There is a specific type of emptiness in moving to a new place to start a new job or start at a new school and not having a life figured out there yet and not really knowing anyone there yet and being faced with the blank-slate openness of Saturday and Sunday and realizing you’re just trying to make it through the weekend to get back to having Some Defined Purpose again on Monday.

I don’t enjoy having time that’s been unaccounted for because it immediately makes me feel like I should be doing something with it, and then I can’t think of anything that I could possibly be doing that would be worthwhile enough to live up to the raw potential of any amount of available time.

This is a learned response. People will forgive you for not doing anything else with your time or for not having any free time at all if you’re busy, I tell myself. People will praise you for working more, for finding more time to be productive. Every time I do this, I reinforce this attitude and this lie that work is more important than anything else, and I fall deeper and deeper for it.

Sometimes, when something falls away naturally, it forms roots of its own.

A friend asked me, after an Objectively Good And Exciting Thing happened, if I celebrated it. I laughed it off with a “Ha! no,” which I still feel bad about.

Another part of my fear of celebrating something as Really Happening is the fear that celebrating it will make me unable to be critical about it, which I fear will make me unable to do a good job at it. I have been trying to tell myself that I can have joy for something and still be critical of it, it’s just that I’ll become attentive out of love, instead of being critical out of fear, or out of anxiety, or out of some illusion of objective detachment, right?

When you truly fall in love with something, aren’t you even more attentive and detailed toward it? After all, not everything out in the world is something you love, right? Loving something is very specific, nuanced.

I try for the joyful approach, but—you know—loving something is one of those things that is hard to acknowledge as Really Happening, too.

I have taught myself to feel like I am constantly failing everyone around me because it pushes me to get things done. I know it’s not healthy, but it works because when I make myself feel like I’m letting everyone down all the time, and when I feel like I am always disappointing everyone, then I don’t want to disappoint them more, and so I try to work harder to make them less disappointed in me.

I have tried to become more attentive to words that treat natural elements of ourselves as currency: “paying attention,” “spending time,” “wasting energy.” I have tried to catch myself whenever I use words and phrases like this, and when I do, I try to use other words—“giving my attention,” “sharing my time,” “using my energy”—but I have to go against this immediate, split-second resistance to using words that do not promise that I get something in return for “spending” myself on something.

I am trying to pressure myself less on what a friendship “should” be. Is it not enough to see someone once a year when we live in different cities and one of us is passing through the other’s? Or get coffee once a year with a friend who lives in the same city when we are both overwhelmed and underwater with the rest of our lives?

Or, maybe nostalgia is to feel a happiness about something that is over because it is over. That in order to feel happy about it, it must be something that you can’t go back to and affect, that you can’t mess up from where you are now, but also, that you can’t really feel at all.

This Is Who You Are Right Now. And it’s hard to intentionally keep the screen full of holes instead of completing the rows, but these incomplete rows are the proof that I’m working on something and they are the proof that I exist and they are there to prevent me from ever feeling like I am staring at a blank screen, worrying if I’ll ever be able to fill this emptiness again.

HOW TO COOK A TEA EGG

Listen to your loved one ask you why you peel eggs that way. Ask, “Doesn’t everyone? It makes so much sense.” Listen to your loved one say, “No, I’ve never seen it done that way.” Realize you do not know. Wonder why you crack eggs this way.

Realize how, after all these years, you thought that making tea eggs was something you were just supposed to figure out yourself, or something that you were just supposed to have absorbed from your parents in some unspoken passing of intergenerational knowledge. But all you really needed to do was ask.

HOW TO CRACK A BOILED EGG Self Look up from reading your dad’s texts. Suddenly realize that this is why you crack your eggs this way. Try to hold back whatever this feeling is.

My parents have a way of knowing every time a new Chinese restaurant opens in Toronto, and will—it seems to me—have tried them all by the time they open, and will have decided on a detailed review of each of them (“very good” or “too oily” or “too salty” or “better, but a higher price” or “worse and a higher price”), and then will exclusively go to the ones that they deem their favorites, until they are friends with the owners, chefs, and entire waitstaffs. (It seems to be that their favorite restaurants are often the ones where all three roles are held by the same person.)

To be Asian in (North) America is to keep a short running list of places where you know you will be given the gift of being seen as more than a visitor.

In retrospect, perhaps this was one of those desires that we have when we are younger that we don’t really understand the meaning of until we grow up. At that age, perhaps, we’d already absorbed and found a way to articulate one of the more enticing promises of capitalism—of buying, or spending, your way into belonging.

“See, I’m a person who people know, and people like me.”

this is the Only Place That Exists and has ever existed. The only thing that matters is that you are here now, and this is what’s in front of you. And what’s in front of you is everything.

All my parents’ favorite restaurants seem to operate the same way, in that they all have waiting built into them. We have to wait for long periods of time, for us to be seated, for the menu to come by, for us to order, for the food to come, for the dishes to be taken away, for the bill to come, for the bill to come back. These moments say, You’re not leaving for a while. Sit for a moment. Get used to it.

The purpose of all this waiting, it feels like, is to draw our attention and focus inward to what’s here with us at this moment—to the meal, to each other. A good restaurant, it feels, is a place to go to enjoy waiting. It is a place where waiting is the point.

And I used to be annoyed by their insistence to sit too long, to eat too fully, but now I realize, maybe this becomes the point: The leaving is more joyous when you have become too full of the place where you are.

Feeling lonely is for people who have arrived somewhere, I tell myself, not for people still on the way there.

We cannot seem to escape the desire to feel productive with our time. I’m not sure if that’s by choice or by trauma, that this pressure to produce has been so engrained in us that our deepest fantasies are still tied to some idea of working on something.

I prefer to talk very little. When it’s with someone I care about, I love listening, and I always feel that listening is a better way than talking for me to express my love.

it cannot be by coincidence that “decide” and “decode” are only one letter apart.

One way of coping with my anxiety has been to imagine it as a tax. In order to do the things I want to do, in order to go about my life, or to get anything done, I just need to pay the anxiety tax first. The tension and soreness I feel in my shoulders that never goes away; the hour of preparation it takes for me to talk myself into leaving the house; the constant fear that I will say the wrongest thing or write the wrongest thing or do the wrongest thing without even knowing it—these are all part of the tax.

This particular anxiety, this desperation, I think is less about making the work—but more because it may be one of the only ways I know how to make friends. Working on something with someone who cares about making the same thing you do feels to me like the only real way to find someone who shares the same interests and the same passions as you do.

If I am able to contribute my time, my energy, my attention, and my productivity to something, I am adding some tangible value to this friendship, right? I’m worth being friends with, right? I’m not wasting their time, right?

Perhaps there is one other way I feel like I know how to make friends. I feel like I’m a good therapy friend.

A therapy friend is a friend who is an outsider to all of your circles of friends and to everyone else you know who listens to your problems (generally about everyone else you know, or about things that everyone else you know can’t know that you worry about) and who you can confide in because they are an outsider.

I think to get to the point where I can understand that I’ve changed, I have to dissociate from any past version of myself first. I have to treat those past versions of myself as outside of me, so I can see how I am different from those past selves.

There are past versions of me who believe in me, and there are future versions of me who are looking back on where I am and thinking, That’s the version of me who actually managed to achieve something. There are always these people cheering me on, or, at the very least, thinking about me. And that helps me feel less alone. And that helps me feel like I am right where I need to be.

I think perhaps what’s so difficult about trying to witness our own changes is that we are not above the water. We are each just moving up and down in place, trying to stay afloat.

Taking the time to be around nature is helping me understand that things can just exist, being what they are, and it’s just each of us that gives them some sort of meaning.

I loved knowing that in some folder, the act of talking to a friend was filling a .txt document with thousands and thousands of words. That by talking, we were writing a novel, or a script, or something even more. And that made it feel like what we were doing was much more than just talking. In writing all these words together, over years and years, it felt like we were collaborating, like we had written a friendship into being.

Or, because I am not brave enough to actually fully do that, to record everything on my phone just as proof that it happened, but to never do anything with it at all.

On finding ways to remember

The selfish part of all this is that I want to be important—I want to be so important that the world here falls apart, stops functioning, after I step out of it. And of course this doesn’t happen. But there’s a part of me that tells myself that if I were important, if I were truly important, my leaving would have had an impact. It would have done something. There would have been a hole that I left behind that people would notice. Instead, everything just keeps going on without me. And it feels like the lesson is, you don’t matter.

But of course any act of leaving creates that hole. Every act of moving is also an act of removing, leaving an empty space where what moved is no longer there. It’s just, the problem with leaving is that you’re never able to stick around to see what you’ve left behind.

Mourning does not only apply to death. You are allowed to mourn change, as well. You can mourn an old home that is gone, or a world around you that has shifted so imperceptibly until one day it no longer feels familiar anymore.