More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

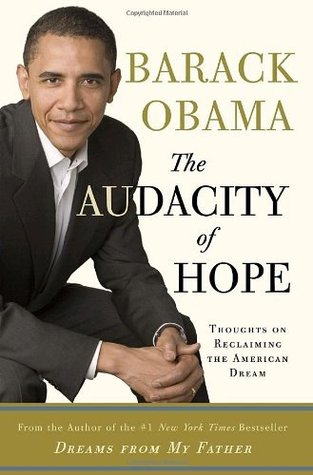

by

Barack Obama

Read between

May 14 - August 18, 2017

It signaled a cynicism not simply with politics but with the very notion of a public life, a cynicism that—at least in the South Side neighborhoods I sought to represent—had been nourished by a generation of broken promises.

In response, I would usually smile and nod and say that I understood the skepticism, but that there was—and always had been—another tradition to politics, a tradition that stretched from the days of the country’s founding to the glory of the civil rights movement, a tradition based on the simple idea that we have a stake in one another, and that what binds us together is greater than what drives us apart, and that if enough people believe in the truth of that proposition and act on it, then we might not solve every problem, but we can get something meaningful done.

But the years had also taken their toll. Some of it was just a function of my getting older, I suppose, for if you are paying attention, each successive year will make you more intimately acquainted with all of your flaws—the blind spots, the recurring habits of thought that may be genetic or may be environmental, but that will almost certainly worsen with time, as surely as the hitch in your walk turns to pain in your hip.

Someone once said that every man is trying to either live up to his father’s expectations or make up for his father’s mistakes, and I suppose that may explain my particular malady as well as anything else.

It was an ill-considered race, and I lost badly—the sort of drubbing that awakens you to the fact that life is not obliged to work out as you’d planned.

Even the legislative work, the policy making that had gotten me to run in the first place, began to feel too incremental, too removed from the larger battles—over taxes, security, health care, and jobs—that were being waged on a national stage.

DENIAL, ANGER, bargaining, despair—I’m not sure I went through all the stages prescribed by the experts. At some point, though, I arrived at acceptance—of my limits, and, in a way, my mortality.

I spent more time at home, and watched my daughters grow, and properly cherished my wife, and thought about my long-term financial obligations. I exercised, and read novels, and came to appreciate how the earth rotated around the sun and the seasons came and went without any particular exertions on my part.

My argument, however, is that we have no choice. You don’t need a poll to know that the vast majority of Americans—Republican, Democrat, and independent—are weary of the dead zone that politics has become, in which narrow interests vie for advantage and ideological minorities seek to impose their own versions of absolute truth.

Religious or secular, black, white, or brown, we sense—correctly—that the nation’s most significant challenges are being ignored, and that if we don’t change course soon, we may be the first generation in a very long time that leaves behind a weaker and more fractured America than the one we inherited.

I am angry about policies that consistently favor the wealthy and powerful over average Americans, and insist that government has an important role in opening up opportunity to all.

I wish the country had fewer lawyers and more engineers.

Which perhaps indicates a second, more intimate theme to this book—namely, how I, or anybody in public office, can avoid the pitfalls of fame, the hunger to please, the fear of loss, and thereby retain that kernel of truth, that singular voice within each of us that reminds us of our deepest commitments.

Recently, one of the reporters covering Capitol Hill stopped me on the way to my office and mentioned that she had enjoyed reading my first book. “I wonder,” she said, “if you can be that interesting in the next one you write.” By which she meant, I wonder if you can be honest now that you are a U.S. senator. I wonder, too, sometimes. I hope writing this book helps me answer the question.

In the world’s greatest deliberative body, no one is listening.

After the family and friends went home, after the receptions ended and the sun slid behind winter’s gray shroud, what would linger over the city was the certainty of a single, seemingly inalterable fact: The country was divided, and so Washington was divided, more divided politically than at any time since before World War II.

Everything was contestable, whether it was the cause of climate change or the fact of climate change, the size of the deficit or the culprits to blame for the deficit.

With the rest of the public, I had watched campaign culture metastasize throughout the body politic, as an entire industry of insult—both perpetual and somehow profitable—emerged to dominate cable television, talk radio, and the New York Times best-seller list.

I don’t claim to have been a passive bystander in all this. I understood politics as a full-contact sport, and minded neither the sharp elbows nor the occasional blind-side hit.

Maybe peace would have broken out with a different kind of White House, one less committed to waging a perpetual campaign—a White House that would see a 51–48 victory as a call to humility and compromise rather than an irrefutable mandate.

When I see Ann Coulter or Sean Hannity baying across the television screen, I find it hard to take them seriously; I assume that they must be saying what they do primarily to boost book sales or ratings, although I do wonder who would spend their precious evenings with such sourpusses.

When Democrats rush up to me at events and insist that we live in the worst of political times, that a creeping fascism is closing its grip around our throats, I may mention the internment of Japanese Americans under FDR, the Alien and Sedition Acts under John Adams, or a hundred years of lynching under several dozen administrations as having been possibly worse, and suggest we all take a deep breath.

We know that global competition—not to mention any genuine commitment to the values of equal opportunity and upward mobility—requires us to revamp our educational system from top to bottom, replenish our teaching corps, buckle down on math and science instruction, and rescue inner-city kids from illiteracy. And yet our debate on education seems stuck between those who want to dismantle the public school system and those who would defend an indefensible status quo, between those who say money makes no difference in education and those who want more money without any demonstration that it will

...more

Privately, those of us in government will acknowledge this gap between the politics we have and the politics we need. Certainly Democrats aren’t happy with the current situation, since for the moment at least they are on the losing side, dominated by Republicans who, thanks to winner-take-all elections, control every branch of government and feel no need to compromise. Thoughtful Republicans shouldn’t be too sanguine, though, for if the Democrats have had trouble winning, it appears that the Republicans—having won elections on the basis of pledges that often defy reality (tax cuts without

...more

Like all good conspiracy theories, both tales contain just enough truth to satisfy those predisposed to believe in them, without admitting any contradictions that might shake up those assumptions.

And we will need to remind ourselves, despite all our differences, just how much we share: common hopes, common dreams, a bond that will not break.

As I listened to the old man reminisce, about Dwight Eisenhower and Sam Rayburn, Dean Acheson and Everett Dirksen, it was hard not to get swept up in the hazy portrait he painted, of a time before twenty-four-hour news cycles and nonstop fund-raising, a time of serious men doing serious work. I had to remind myself that his fondness for this bygone era involved a certain selective memory: He had airbrushed out of the picture the images of the Southern Caucus denouncing proposed civil rights legislation from the floor of the Senate; the insidious power of McCarthyism; the numbing poverty that

...more

Still, there’s no denying that American politics in the post–World War II years was far less ideological—and the meaning of party affiliation far more amorphous—than it is today. The Democratic coalition that controlled Congress through most of those years was an amalgam of Northern liberals like Hubert Humphrey, conservative Southern Democrats like James Eastland, and whatever loyalists the big-city machines cared to elevate. What held this coalition together was the economic populism of the New Deal—a vision of fair wages and benefits, patronage and public works, and an ever-rising standard

...more

It was the sixties that upended these political alignments, for reasons and in ways that have been well chronicled. First the civil rights movement arrived, a movement that even in its early, halcyon days fundamentally challenged the existing social structure and forced Americans to choose sides. Ultimately Lyndon Johnson chose the right side of this battle, but as a son of the South, he understood better than most the cost involved with that choice: upon signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he would tell aide Bill Moyers that with the stroke of a pen he had just delivered the South to the

...more

But I was too young at the time to fully grasp the nature of those changes, too removed—living as I did in Hawaii and Indonesia—to see the fallout on America’s psyche. Much of what I absorbed from the sixties was filtered through my mother, who to the end of her life would proudly proclaim herself an unreconstructed liberal. The civil rights movement, in particular, inspired her reverence; whenever the opportunity presented itself, she would drill into me the values that she saw there: tolerance, equality, standing up for the disadvantaged.

All of which may explain why, as disturbed as I might have been by Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, as unconvinced as I might have been by his John Wayne, Father Knows Best pose, his policy by anecdote, and his gratuitous assaults on the poor, I understood his appeal.

WHAT I FIND remarkable is not that the political formula developed by Reagan worked at the time, but just how durable the narrative that he helped promote has proven to be. Despite a forty-year remove, the tumult of the sixties and the subsequent backlash continues to drive our political discourse.

Indeed, by the end of his presidency, Clinton’s policies—recognizably progressive if modest in their goals—enjoyed broad public support. Politically, he had wrung out of the Democratic Party some of the excesses that had kept it from winning elections. That he failed, despite a booming economy, to translate popular policies into anything resembling a governing coalition said something about the demographic difficulties Democrats were facing (in particular, the shift in population growth to an increasingly solid Republican South) and the structural advantages the Republicans enjoyed in the

...more

Still, when I think about what that old Washington hand told me that night, when I ponder the work of a George Kennan or a George Marshall, when I read the speeches of a Bobby Kennedy or an Everett Dirksen, I can’t help feeling that the politics of today suffers from a case of arrested development. For these men, the issues America faced were never abstract and hence never simple. War might be hell and still the right thing to do. Economies could collapse despite the best-laid plans. People could work hard all their lives and still lose everything.

Not all Republican elected officials subscribe to the tenets of today’s movement conservatives. In both the House and the Senate, and in state capitals across the country, there are those who cling to more traditional conservative virtues of temperance and restraint—men and women who recognize that piling up debt to finance tax cuts for the wealthy is irresponsible, that deficit reduction can’t take place on the backs of the poor, that the separation of church and state protects the church as well as the state, that conservation and conservatism don’t have to conflict, and that foreign policy

...more

Mainly, though, the Democratic Party has become the party of reaction. In reaction to a war that is ill conceived, we appear suspicious of all military action. In reaction to those who proclaim the market can cure all ills, we resist efforts to use market principles to tackle pressing problems. In reaction to religious overreach, we equate tolerance with secularism, and forfeit the moral language that would help infuse our policies with a larger meaning. We lose elections and hope for the courts to foil Republican plans. We lose the courts and wait for a White House scandal.

The accepted wisdom that drives many advocacy groups and Democratic activists these days goes something like this: The Republican Party has been able to consistently win elections not by expanding its base but by vilifying Democrats, driving wedges into the electorate, energizing its right wing, and disciplining those who stray from the party line. If the Democrats ever want to get back into power, then they will have to take up the same approach.

am convinced that whenever we exaggerate or demonize, oversimplify or overstate our case, we lose. Whenever we dumb down the political debate, we lose. For it’s precisely the pursuit of ideological purity, the rigid orthodoxy and the sheer predictability of our current political debate, that keeps us from finding new ways to meet the challenges we face as a country.

I imagine they are waiting for a politics with the maturity to balance idealism and realism, to distinguish between what can and cannot be compromised, to admit the possibility that the other side might sometimes have a point. They don’t always understand the arguments between right and left, conservative and liberal, but they recognize the difference between dogma and common sense, responsibility and irresponsibility, between those things that last and those that are fleeting.

The openness of the White House said something about our confidence as a democracy, I thought. It embodied the notion that our leaders were not so different from us; that they remained subject to laws and our collective consent.

“Want some?” the President asked. “Good stuff. Keeps you from getting colds.” Not wanting to seem unhygienic, I took a squirt. “Come over here for a second,” he said, leading me off to one side of the room. “You know,” he said quietly, “I hope you don’t mind me giving you a piece of advice.” “Not at all, Mr. President.” He nodded. “You’ve got a bright future,” he said. “Very bright. But I’ve been in this town awhile and, let me tell you, it can be tough. When you get a lot of attention like you’ve been getting, people start gunnin’ for ya. And it won’t necessarily just be coming from my side,

...more

So Democratic audiences are often surprised when I tell them that I don’t consider George Bush a bad man, and that I assume he and members of his Administration are trying to do what they think is best for the country.

Moreover, whenever I write a letter to a family who has lost a loved one in Iraq, or read an email from a constituent who has dropped out of college because her student aid has been cut, I’m reminded that the actions of those in power have enormous consequences—a price that they themselves almost never have to pay.

It is to say that after all the trappings of office—the titles, the staff, the security details—are stripped away, I find the President and those who surround him to be pretty much like everybody else, possessed of the same mix of virtues and vices, insecurities and long-buried injuries, as the rest of us.

It’s that sense of familiarity that strikes me wherever I travel across Illinois. I feel it when I’m sitting down at a diner on Chicago’s West Side. I feel it as I watch Latino men play soccer while their families cheer them on in a park in Pilsen. I feel it when I’m attending an Indian wedding in one of Chicago’s northern suburbs. Not so far beneath the surface, I think, we are becoming more, not less, alike.

It is to insist that across Illinois, and across America, a constant cross-pollination is occurring, a not entirely orderly but generally peaceful collision among people and cultures. Identities are scrambling, and then cohering in new ways. Beliefs keep slipping through the noose of predictability. Facile expectations and simple explanations are being constantly upended. Spend time actually talking to Americans, and you discover that most evangelicals are more tolerant than the media would have us believe, most secularists more spiritual. Most rich people want the poor to succeed, and most of

...more

I think Democrats are wrong to run away from a debate about values, as wrong as those conservatives who see values only as a wedge to pry loose working-class voters from the Democratic base. It is the language of values that people use to map their world. It is what can inspire them to take action, and move them beyond their isolation.

These values are rooted in a basic optimism about life and a faith in free will—a confidence that through pluck and sweat and smarts, each of us can rise above the circumstances of our birth. But these values also express a broader confidence that so long as individual men and women are free to pursue their own interests, society as a whole will prosper. Our system of self-government and our free-market economy depend on the majority of individual Americans adhering to these values. The legitimacy of our government and our economy depend on the degree to which these values are rewarded, which

...more

Our individualism has always been bound by a set of communal values, the glue upon which every healthy society depends.

But we cannot avoid these tensions entirely. At times our values collide because in the hands of men each one is subject to distortion and excess. Self-reliance and independence can transform into selfishness and license, ambition into greed and a frantic desire to succeed at any cost.