More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

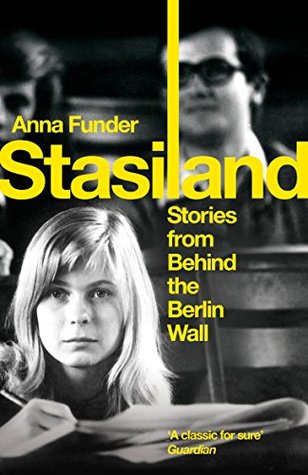

Anna Funder

Read between

January 9 - January 18, 2021

The romance comes from the dream of a better world the German Communists wanted to build out of the ashes of their Nazi past: from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs. The horror comes from what they did in its name. East Germany has disappeared, but its remains are still at the site.

The Stasi was the internal army by which the government kept control. Its job was to know everything about everyone, using any means it chose. It knew who your visitors were, it knew whom you telephoned, and it knew if your wife slept around. It was a bureaucracy metastasised through East German society: overt or covert, there was someone reporting to the Stasi on their fellows and friends in every school, every factory, every apartment block, every pub. Obsessed with detail, the Stasi entirely failed to predict the end of Communism, and with it the end of the country. Between 1989 and 1990 it

...more

My favourites were the pictures of protesters occupying the building on 4 December 1989, squatting in the corridors with the surprise still on their faces, as if half-expecting to be asked to leave. As they entered the building, the Stasi guards had asked to see the demonstrators’ identity cards, in a strange parody of the control they were, at that very moment, losing. The demonstrators, in shock, obediently pulled their cards from their wallets. Then they seized the building.

To remember or forget—which is healthier? To demolish it or to fence it off? To dig it up, or leave it lie in the ground?

After the Wall fell the German media called East Germany ‘the most perfected surveillance state of all time’. At the end, the Stasi had 97,000 employees—more than enough to oversee a country of seventeen million people. But it also had over 173,000 informers among the population. In Hitler’s Third Reich it is estimated that there was one Gestapo agent for every 2000 citizens, and in Stalin’s USSR there was one KGB agent for every 5830 people. In the GDR, there was one Stasi officer or informant for every sixty-three people. If part-time informers are included, some estimates have the ratio as

...more

Unlike secret services in democratic countries, the Stasi was the mainstay of State power. Without it, and without the threat of Soviet tanks to back it up, the SED regime could not have survived.

By comparison with other Eastern Bloc countries, East Germany never had much of a culture of opposition. Perhaps this was in part due to the better standard of living, perhaps to the thoroughness of the Stasi—or, as some put it, to the willingness of Germans to subject themselves to authority. But mostly it was because, alone of all Eastern Bloc countries, East Germany had somewhere to dump people who spoke out: West Germany. It imprisoned them and then sold them to the west for hard currency. The numbers of dissidents could not reach a critical mass until 1989 when the changes in the Soviet

...more

In August, the Hungarians cut the barbed wire at their border with Austria, creating the first hole in the Eastern Bloc. Thousands of East Germans flocked there and ran, crying with relief and anger, across the border. Thousands more travelled to the West German embassies in Prague and Warsaw and set up camp, creating a diplomatic nightmare in German–German relations. Finally, the regime agreed to let them out, on condition that the trains taking them to West Germany travel through the GDR. Honecker hoped to humiliate the ‘expellees’ by confiscating their identity papers. And he wanted them to

...more

On 9 November, thinking to deal with the crisis, the Politbüro met and decided to relax travel restrictions. People would be allowed to travel freely and be prohibited from leaving the country only in ‘special exceptional circumstances’. The session went into the night. At this stage the regime had taken to holding a regular press conference with the international media. That evening, Politbüro member Günter Schabowski needed to get to it. He hadn’t been at the session, but was hastily given a note of its decision to read out at the press conference. When he finished, there was no visible

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

‘I think it’s important, what you’re doing,’ she says, as if to comfort me, and I am ashamed. ‘For anyone to understand a regime like the GDR, the stories of ordinary people must be told. Not just the activists or the famous writers.’ Her eyes, grey-green, have a dark shape in them.

When it moves, I see that it is me. ‘You have to look at how normal people manage with such things in their pasts.’ ‘I think I’m losing track of normal.’ ‘Yes,’ she says, smiling, ‘I know it’s relative. We easterners have an advantage, perhaps, in that we can remember and compare two kinds of systems.’ Her mouth twists into a smile as she collects her cigarettes and lighter and puts them in her pocket. ‘But I don’t know if that’s an advantage. I mean you see the mistakes of one system—the surveillance—and the mistakes of the other—the inequality—but there’s nothing you could have done in the

...more

am mulling over the idea of the GDR as an article of faith. Communism, at least of the East German variety, was a closed system of belief. It was a universe in a vacuum, complete with its own self-created hells and heavens, its punishments and redemptions meted out right here on earth. Many of the punishments were simply for lack of belief, or even suspected lack of belief. Disloyalty was calibrated in the minutest of signs: the antenna turned to receive western television, the red flag not hung out on May Day, someone telling an off-colour joke about Honecker just to stay sane.

And almost overnight the Germans in the eastern states were made, or made themselves, innocent of Nazism. It seemed as if they actually believed that Nazis had come from and returned to the western parts of Germany, and were somehow separate from them—which was in no way true. History was so quickly remade, and so successfully, that it can truly be said that the easterners did not feel then, and do not feel now, that they were the same Germans as those responsible for Hitler’s regime. This sleight-of-history must rank as one of the most extraordinary innocence manoeuvres of the century.

As well as leaving to work in the western sector each day, hundreds and later thousands of refugees started leaving the eastern sector for good. By 1961 about 2000 people were leaving the east each day through West Berlin. Koch says his thinking was orthodox for the time. ‘These people were shirking the hard work that had to be done here in order to build a better future for themselves—they wanted to enjoy their lives right here, right now.’ It was as if that were a moral failure, a religious falling off the branch—who are these people who will reap where they have not sown? The GDR was

...more

I once saw a note on a Stasi file from early 1989 that I would never forget. In it a young lieutenant alerted his superiors to the fact that there were so many informers in church opposition groups at demonstrations that they were making these groups appear stronger than they really were. In one of the most beautiful ironies I have ever seen, he dutifully noted that it appeared that, by having swelled the ranks of the opposition, the Stasi was giving the people heart to keep demonstrating against them.

‘The mistake the GDR made was to force people into a position,’ the dark man says, ‘either you are for us or an enemy. And if you then came to think of yourself as an enemy you had to ask yourself: what am I doing here? They wanted to put everything into their narrow schema, but life simply didn’t fit into it.’ He pauses, and the others wait for him to finish. ‘I think we need to remember that they came here for the freedom, not for fifteen kinds of ketchup.’

Herr Raillard sees me out. I check with him what the consequences were when someone who had been approached to inform either told people about it or flatly refused. ‘There really were no consequences,’ he says. ‘That was the thing. The file was just closed, marked “dekonspiriert”. But of course,’ he adds, ‘no-one could know at the time that nothing would happen to him. So hardly anyone refused.’