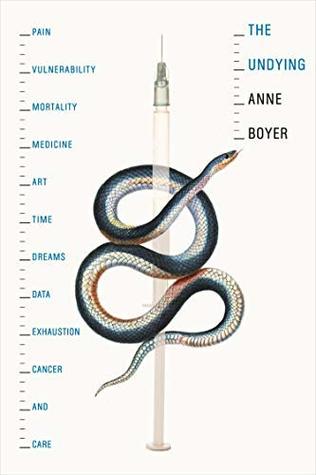

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Anne Boyer

Read between

October 18 - October 28, 2025

To be declared with certainty ill while feeling with certainty fine is to fall on the hardness of language without being given even an hour of soft uncertainty in which to steady oneself with preemptive worry, aka now you don’t have a solution to a problem, now you have a specific name for a life breaking in two.

radiology turns a person made of feelings and flesh into a patient made of light and shadows.

Our senses tell us almost nothing about our illness, but the doctors ask us to believe that what we cannot see or feel might kill us, and so we do. “They tell me,” said an old man to me in the chemotherapy infusion room, “I have cancer, but,” he whispered, “I have my doubts.”

Cancer doesn’t feel real. Cancer feels like an alien that industrial capitalist modernity has worried into an encounter: mid-astral, semi-sensory, all terrible. Cancer’s treatment is like a dream from which we only half-wake to find that half-waking is another chapter in the book of the dream, a dream that is a document and a container for both waking and sleep, any pleasure and all pain, the unbearable nonsense and with it all erupted meaning, every moment of the dream too vast to forget and every recollection of it amnesiac.

Should I live or should I die? But nothing was that frankly posed. As soon as a patient lies down on the exam table, she has laid down her life on a bed of narrowed answers, but the questions are never sufficiently clear.

No one knows you have cancer until you tell them.

is decided without ceremony that the doctors will eventually take my breasts from me and discard them in an incinerator, and because of it, I begin the practice of pretending that my breasts were never there.

I begin to collect images of Saint Agatha holding her amputated breasts on a platter. Agatha is the patron saint of breast cancer, fires, volcanic eruptions, single women, torture victims, and the raped. She is also the patron saint of earthquakes, because when the torturers amputated her breasts, the ground began to tremble in revenge.

In chemotherapy, as in war, when you are being exposed to cyclophosphamide, it is advisable that you have someone to hold your hand.

Then people leave, friends drop off, lovers abscond with all possibility of you ever again being fond of them, colleagues avoid you, your rivals are now unimpressed, your Twitter followers unfollow. To the people who have left you, it is possible you are either the most object-like of all possible objects (that you are to someone a thing to be discarded like trash) or the most human that you can be in the situation of this illness (for how strongly, on being discarded, you feel forlorn). Or, as you have learned that anything is possible during catastrophic illness, you could be the most human

...more

I have always wanted to do everything and know everything and be everywhere, and because of this, I feel left out, captive, bored. But mostly I feel asynchronous—both hurried and left behind. Time, apart from pain, work, family, mortality, medicine, information, aesthetics, history, truth, love, literature, and money, is cancer’s other big problem.

“Fuck cancer”9 is always the wrong slogan if for no other reason than that the cancer is your own body growing inside you, but also because “cancer” is a historically specific, socially constructed imprecision and not an empirically established monolith. This whole time I’ve been writing about cancer, I’ve been writing about something that scientists agree doesn’t quite exist, at least not as one unified thing. Fuck white supremacist capitalist patriarchy’s ruinous carcinogenosphere would be a lot better, but it is a difficult slogan to fit on a hat.

If I calculated the cost of each breath I took after this cancer, I should breathe out stock options. My life was a luxury good, but I was corroded, I was mutilated, I was uncertain. I was not okay.

Every movie I watch now is a movie about an entire cast of people who seem to not have cancer, or at least this is, to me, its plot.

Being sick makes excessive space for thinking, and excessive thinking makes room for thoughts of death.

There was one spot, on the side of what would be my new left breast, that hurt like an emergency. There was one spot, on the side of what would be my new right breast, that hurt like a minor emergency.

Immobilized in bed, I decide to devote my life to making the socially acceptable response to news of a diagnosis of breast cancer not the corrective “stay positive,” but these lines from Diane di Prima’s poem “Revolutionary Letter #9”: “1. kill head of Dow Chemical / 2. destroy plant / 3. MAKE IT UNPROFITABLE FOR THEM to build again.”11

Every person with a body should be given a guide to dying as soon as they are born.

In the capitalist medical universe in which all bodies must orbit around profit at all times, even a double mastectomy is considered an outpatient procedure.

Pain is a fluorescent feeling.

We can’t think ourselves free, but that’s no reason not to get an education.

Tissue-expander breast reconstruction is widely regarded as very painful, the kind of process that requires you to sign consent forms for your future opiate addiction.

A cancer patient can tell herself why what is done to her must be done, but this does not often fix the feeling that she has been cut up, poisoned, harvested, amputated, implanted, punctured, weakened, and infected, often all at once.

LifeCell (corporate vision: “surgery without complications”) brands the sterilized cadaver skin4 used as a sling for breast implants as “Alloderm,” but hygienic nominalism could do nothing to afford how this fraction of a dead person implanted in me filled the dream life of April 2015 with a wide and recurring version of a cadaver’s terror.

Like any mortal creature, I should not get too attached to being alive.

I’d survived, yet the ideological regime of cancer means that to call myself a survivor still feels like a betrayal of the dead. But I’ll admit that not a day passes in which I am not ecstatic that I still get to live.