More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

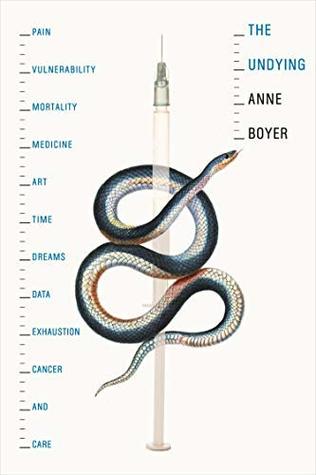

Anne Boyer

Read between

November 29 - December 13, 2024

Our genes are tested: our drinking water isn’t. Our body is scanned, but not our air.

diagnosis. In the United States, if you aren’t someone’s child, parent, or spouse, the law allows no one else guaranteed leave from work to take care of you.7 If you are loved outside the enclosure of family, the law doesn’t care how deeply—even with all the unofficialized love in the world enfolding you, if you need to be cared for by others, it must be in stolen slivers of time.

The history of illness is not the history of medicine—it is the history of the world—and the history of having a body could well be the history of what is done to most of us in the interest of the few.

The work of care and the work of data exist in a kind of paradoxical simultaneity: what both hold in common is that they are done so often by women, and like all that has historically been identified as women’s work, it is work that can go by unnoticed.

thing. Fuck white supremacist capitalist patriarchy’s ruinous carcinogenosphere would be a lot better, but it is a difficult slogan to fit on a hat.

Cancer can be a stage of virtue on which others can act, and it is also a pure instance of suffering in which we have no one—and everything—to blame.

My daughter, who was fourteen years old at the time, said, “Anne, I hate what the world has done to the world.” and “The only choice left is terrorist or shut-in.” I tell my daughter that my BRCA genetic test came back negative. I tell her that without a hormonal cause and without a genetic tendency and without obvious lifestyle factors the cancer I had probably just came from exposure to radiation or random carcinogens, that she doesn’t have to worry that she is predisposed or genetically cursed. “You forget,” she answered, “that I still have the curse of living in the world that made you

...more

Every person with a body should be given a guide to dying as soon as they are born.

It is as if I am both sick with and treated by the twentieth century, its weapons and pesticides, its epic generalizations and its expensive festivals of death. Then, sick beyond sick from that century, I am made sick, again, from information—a sickness that is our century’s own.

Some of us who survive the worst survive it into bare inexistence. Aelius Aristides described this, too: “Thus I was conscious of myself as if I were another person, and I perceived my body ever slipping away, until I was nearly dead.”

According to one study by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, “45 percent of mastectomies in 2013 were performed in hospital-affiliated outpatient surgery centers with no overnight stay.”

Dying of breast cancer is not evidence of the weakness or moral failure of the dead. The moral failure of breast cancer is not in the people who die: it is in the world that makes them sick, bankrupts them for a cure that also makes them sick, then, when the cure fails, blames them for their own deaths.

The exhausted might almost do what they are supposed to do, but as a consequence of their depletion, they almost never do what they want.

Sleep, which is often the remedy for tiredness, disappoints the exhausted. Sleep is full of the work of dreams, full of the way that sleep begets more sleep, full of the way that more sleep can beget more exhaustion, and that more exhaustion begets more exhaustion for which the remedy is almost never just sleep.