More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

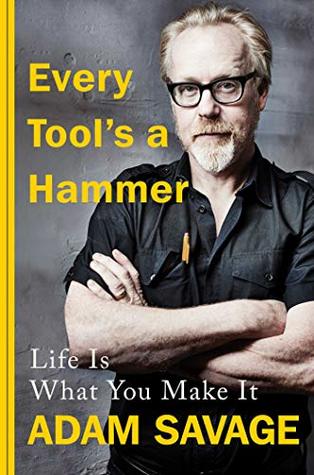

Adam Savage

Read between

October 6 - December 8, 2019

Great question. The answer is structure. The internal structure of the atoms and molecules that make up the harder steel has been “adjusted.” One of the most common ways to do that is with heat. Heat can do magical and amazing things to steel. You can very finely adjust its ductility (malleability), its flexibility, or its hardness, for example, solely with the process by which you heat the steel and how quickly you let it cool.

Using more cooling fluid is a reminder to myself to sloooooow doooooown, to reduce the friction in my life—in my work, in my schedule, in relationships, everywhere, really. It’s a warning against my proclivity for serial impatience.

do the job right the first time. Taking the time to organize your thoughts; to organize your work space; to organize your tools. It’s time, when taken, that you might feel is slowing you down in the moment, but in fact is saving you time in the long run.

Examine your work space for all items not in use—tools, materials, books, coffee cups, it doesn’t matter what it is. 2. Remove those unused items from your space. When in doubt, leave it on the table. 3. Group all like items—pens with pencils, washers with O-rings, nuts with bolts, etc. 4. Align (parallel) or square (90-degree angle) all objects within each group to each other and then to the surface upon which they sit.

By forcing me to slow down (which I’ve learned actually allows me to work faster),

I approached it a little bit differently than I normally do. I pulled all the bowls out, I put all my dry ingredients in one set, I had all my wet ingredients separated in another, and then I put it all together and it was so much easier to do it that way.

get your mise in its proper place is to slow down, address your work properly, and lock your shit down.

In the case of a maker, I mean that literally.

mean by addressing your work. It’s not too much to say that in slowing yourself down, locking your process down, and doing everything the right way, you’re looking into the future that you

want to create, with the things you value at its center.

This thought, which is effectively imposter syndrome, often couples with self-doubt, panic, fear, and uncertainty to tip the scales in the constant internal battle between the security of doing what you’ve always done, more or less consequence-free, and the exciting demands of doing something new for somebody else.

They kept asking me what they could do, but having never truly delegated before, I had no earthly idea. I spent the entirety of my time—a month—building this set thinking that I had everything under control and now that I didn’t, now that I clearly needed help, I had no idea how to utilize it.

I have never felt lower. I called my dad. I needed some guidance. Some kind of advice. I didn’t have the language or the emotional awareness for it at the time, but what I really needed was help. What do I do?

TRYING TO BE A HERO IS A TERRIFIC WAY TO END UP BECOMING THE VILLAIN

Not only is it less efficient, but how do you expect to learn new things or get better if you do everything in isolation? This was my biggest mistake, my truest and deepest failing: my aversion to asking for help. For more years than I would like to admit, “help” was a dirty word.

Let me tell you something: when you are working in a team, making something for somebody else, trying to be the hero is a terrific way to end up becoming the villain.

I get a huge endorphin rush from knowing the right answer to a question, or having the right tool to fix a problem. But I’ve had to learn (the hard way, in some instances) to be really honest about what I do and don’t know. It’s bad enough when you try to fool others into believing that you know what you’re doing; there’s zero percentage in fooling yourself as well, because that only puts you further behind.

The most surprising aspect of learning that lesson, as it burrowed itself into my brain very much against my will, was that when trying to make something work, it was always the smartest people I knew who were the quickest to ask what the hell you were talking about; to ask you to explain; to ask you to help them understand. In this sense, help is more than just an extra pair of hands or an extra set of eyes. Help is expertise. It’s wisdom. It’s learning enough to understand and admit to what you don’t know.

I absorbed a wide range of skills, largely by doing the opposite of what I’d done in New York. Instead of accepting anything that seemed exciting and then going off on my own, pretending that I knew what I was doing, I asked for help when necessary, and gave help whenever wanted. In the process, I learned carpentry, set design, casting and mold making, rigging, costumes, furniture construction, and welding.

I had help to give. We ended up having a perfect funny man/straight man dynamic, and together we could build most anything, including a show that would end up running fourteen seasons, spawn a reboot and a kids’ version,

Part of being the boss of a shop is delegating basic process tasks to your team members so you can focus on the more important, high-level stuff that keeps a shop running: meeting with clients, coming up

with big ideas, paying the bills, that sort of thing.

“How can I help them do it faster?” It’s “Why not just jump in and do it myself?”

It is this tendency that has made me a poor delegator. It’s also made me less productive in the past. My big problem is that I want to do too many things, and if I load them all up on my plate because I know, individually, I can complete each task more

quickly than anyone else, the end result is that noth...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I HAVE to ask for help from my team. I have to delegate.

“One of the things I struggle with is sometimes it’s easier to do something yourself than to train somebody else to think the way that you think about something,”

What am I doing wrong? Why won’t this person ever learn?! It was a regular refrain in my inner dialogue between takes.

Then one day I realized that all the most valuable stuff I ever learned as a maker came in the form of critical feedback from employers or clients—and I was providing almost none of that to my team.

to acknowledge their work, to appreciate their effort, and to correct their mistakes.

but I love working with my team and I don’t want to let anything or anyone ruin that collaborative environment for them.

then you need to be able to deliver the right feedback at the right time.

Deadlines are about helping yourself. I LOVE DEADLINES! They are the chain saw that prunes decision trees. They create limits, refine intention, and focus effort. They are perhaps the greatest productivity tool we have, and you don’t need a Time Life series of books

for not starting or doing or working: I don’t know what to make; I don’t know how to make it; What if I mess up?; I don’t have everything I need.

EVERYONE continuously wants more time, and it’s always the deadline that is the problem, not the budget or the size of the workforce.

He didn’t show any emotion, neither perturbation nor anger, not even nonchalance.

FieldReady.org.

“What is the essence of this project?”

That is what deadlines can do for your creative thinking. They help you cut through the clutter.

In my experience, the ability to take an idea from your own mind and transfer it to the mind of another person is intoxicating.

It is a kind of creative empowerment that makes all your other crazy ideas feel maybe not so crazy.

“You’re a real good shooter,” he said, “your shooting ability is pretty much equivalent to mine. But I just have more knowledge than you. Truthfully, shooting ability is only about twenty percent of what it takes to be a great player. All the rest is knowledge.”

A maker needs to do the same thing with their projects, only on paper. It’s not enough to have an idea of what you want to make. It’s not even enough to have all the skills required to make it—knowing that you can build something isn’t the same as knowing how you’re going to build it.

Here’s something true: there will be times in every single build when a pathway isn’t clear. These roadblocks, or momentum killers as I’ve come to refer to them, aren’t outliers. In fact, they are abundant and nobody is immune to them. Financial problems, procrastination,

fatigue, family obligations, mistakes, accidents, lack of interest, lack of time, poor feedback—any one of these things can bring your project to a screeching halt and destroy all the creative momentum you’ve gathered.

Making things has always been a central pleasure to my life.

Drawing can have that same kind of power for a maker of any age or skill level.

It is a language in which experts and novices alike can communicate, because it is fundamentally the universal language of creation.

One, because it continued to be useful, and two, because it clearly helped me get better at communicating my ideas more precisely.

have a prediction: you are going to mess up a lot. I mean A LOT. Whether from impatience or arrogance, inexperience or insecurity, lack of knowledge or lack of interest, you are going to tear seams, break bits, snap joints, misdrill, overcut, under-measure, miss deadlines, injure yourself, and generally just make a mess of things.