More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

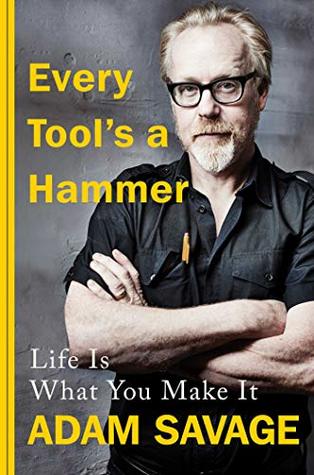

by

Adam Savage

Read between

October 6 - December 8, 2019

Life stories always look like straight lines from the vantage point of looking back, but precious few really are.

it more and more difficult to find meaningful populations of good young makers to share ideas with.

I conclude with some kind of exhortation to keep making stuff, to keep creating, and to keep pushing past self-perceived limits. Because more than anything else, what I continue to fight against is all the ways in which the tools of creation are kept out of the hands of our most dynamic, creative minds.

I code.” I’ve heard this sentiment a lot. “I don’t make, I __________ .” Fill in the blank. Code, cook, craft (not sure why all my examples start with C), the list of exceptions people invent to place themselves on the outside of the club of makers is long and, to me, totally infuriating.

“CODING IS MAKING!” I said enthusiastically to that young man. Whenever we’re driven to reach out and create something from nothing, whether it’s something physical like a chair, or more temporal and ethereal, like a poem, we’re contributing something of ourselves to the world. We’re taking our experience and filtering it through our words or our hands, or our voices or our bodies, and we’re putting something in the culture that didn’t exist before. In fact,

Putting something in the world that didn’t exist before is the broadest definition of making, which means all of us can be makers. Creators.

This is the risk of all creative spirits: every project has as many obstacles as solutions, and with each one there is the chance that one might not end up satisfied with the results; or that others might not be satisfied with them, either, and can’t wait to tell you about it.

The internet is far from fulfilling its promise to be the compendium of all human knowledge, it’s more like the outline or the index.

nothing we make ever turns out exactly as we imagined; that this is a feature not a bug; and that this is why we do any of it. The trip down any path of creation is not A to B. That would be so boring. Or even A to Z. That’s too predictable. It’s A to way beyond zebra. That’s where the interesting stuff happens. The stuff that confounds our expectations. The stuff that changes us.

When we say we need to teach kids how to “fail,” we aren’t really telling the full truth. What we mean when we say that is simply that creation is iteration and that we need to give ourselves

the room to try things that might not work in the pursuit of something that will. Wrong turns are part of every journey. They are, as Kurt Vonnegut was fond of saying, “dancing lessons from God,” and the last thing we want to do is give our kids two left feet.

the first law of thermodynamics: an object at rest tends to stay at rest unless acted upon by an outside force. Which is to say, to get started you need to become the outside force that starts the (mental and physical) ball rolling, which overcomes the inertia of inaction and indecision, and begins the development of real creative momentum.

My battle is usually with time and resources more than worrying about what my next project will be.

obsession. In my experience, bringing anything into the world requires at least a small helping of obsession.

Obsession is the gravity of making. It moves things, it binds them together, and gives them structure. Passion (the good side of obsession) can create great things (like ideas), but if it becomes too singular a fixation (the bad side of obsession), it can be a destructive force.

How does your brain work? What is your secret thrill? How do you process your world?

I could see many of them snickering, suppressing smiles. Here was that complicated moment, again. I was completely exposed. In those younger years, this would have been a slow-motion nightmare.

Tested.com, my website devoted to the process and tools for making in all its myriad forms.

Ralph Waldo Emerson says: “To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men—that is genius.”

Every single one of us is trying to make sense of the world—our place in it, and how everything fits together. We learn as much about ourselves and our surroundings from the stories we choose to tell, as from the stories others choose to tell us.

But what does that mean, to go deep? As a maker, it means interrogating your interest in something and deconstructing the thrill it gives you. It means understanding why this thing that has captured your attention has not let go, and what about it keeps bringing you back. It means giving yourself over to your obsession.

“No matter what you’re making, no matter how good you are, you’re gonna run into a thing that you don’t know how to do or something goes wrong with your materials or you’re running out of time, or whatever. And if you’re not devoted to that thing, if you’re not completely obsessed with that thing, you will stop,”

accident. I think Kubrick wants us to understand that the tragedy of war is that it’s often envisioned by idiots and executed by professionals.

But your ideas can come from anywhere. They are out there, floating everywhere. It will be your interest and obsession that create the gravity that draws them to you and then makes them yours.

I’d have rejected the idea out of hand. List making was the death of creativity! It was a stultifying tool of the ordered, methodical, measured, boring universe.

I think a lot of creative people look at planning tools like list making that way at some point in their lives. Planning is for parents. Lists are for accountants and teachers and bureaucrats and all the other agents of creative repression! But here’s the thing: lists aren’t external to the creative process, they are intrinsic to it.

Now I love lists. I like long detailed lists. I like big unruly lists. I like sorting unsorted lists into outline form, then separating out their topics into lists of their own. Every single project I do involves the making of lists.

The China Syndrome, the 1979 nuclear disaster film starring Jane Fonda and Michael Douglas

manageable project in my head instead

of an endless series of separate, overwhelming tasks. This, I quickly understood, is the abiding power of a well-made list.

In medicine, simple checklists, like the Apgar score, have saved countless babies’ lives, and saved countless hospitals hundreds of millions of dollars in waste. In aviation, compiling reams of instructions has become a list-making science of precise font-size, field-tested readability, and total items allowed per page.

The closer you look, the longer it gets, as will the lists you create to incorporate all the new, changed information.

we were done and here is how he explained his process: If a task was completed, he colored in the corresponding box on the list. If a task was halfway or mostly complete, he colored in half its box diagonally. If a task hadn’t been started or measurable progress had yet to be achieved, that box stayed empty.

The value of a list is that it frees you up to think more creatively, by defining a project’s scope and scale for you on the page, so your brain doesn’t have to

hold on to so much information.

HOW I MAKE LISTS

Step 1: The Brain Dump My method of list making is not to make a single list per project, but rather to make a series of lists that helps me define it as it goes.

“Can we just all agree right now, this is going to suck? Whatever we’re talking about now, no matter how much we’re getting excited, let’s just all understand it’s going to be a mess.”

“you’ve got to do at least six iterations, minimum, of any project before it starts getting good enough to share it with other people.”

get overwhelmed by the sheer volume of it all. The brain dump is still a useful list, don’t misunderstand, just not in its current form. It is simply the first step of the process.

Step 2: The Big Chunks Step 2 is to take that massive list and start to carve it into manageable chunks.

Step 3: The Medium Chunks With the big chunks laid out and preliminarily itemized, I reorganize the components into medium chunks by subcategory.

I find making lists to be one of the greatest stress reducers besides meditation.

Step 4: Diving In Now it’s time to get working. I almost never begin at the beginning. Usually I examine the subcategorized list and I look for the toughest nut to crack.

start. I do this for three reasons: 1) I don’t want to get caught out toward the end of a project with unexpected problem solving that takes way longer than I expected; 2) once I’ve cracked the tough problem, I’ve built a lot of momentum, and I’ve already slayed the beast that might kill my momentum later on; and 3) I like coasting to the finish with the easy stuff. It’s one of the ways I manage the stress of a project. Get the hard stuff out of the way first, then the specter of all those empty checkboxes becomes less intimidating because the tasks get successively easier and the checkboxes

...more

Step 5: Make More Lists Once you’ve made your proper nested master list, and you’ve dived into the making process, you’re not done with list making.

Step 6: Put It Away for a Bit All the list making I’ve described so far has been about project management

and measurement and momentum. But there’s one more list I regularly make, that stands apart from those.

often make this kind of list on planes, and in green rooms, or coffee shops. It’s the list I make when I quit a project. I frequently abandon projects, for various reasons. Life, travel, TV shows, more important projects—there are lots of reasons that I’ll shelve some projects.

sourpuss.