More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

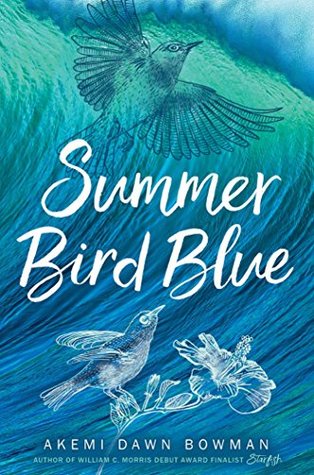

Summer.” “Bird.” “Blue.”

I need to have something that doesn’t feel like it belonged to Lea.

When the salt water erupts from my lungs, I feel it heave up my throat and out of my mouth. Water is supposed to be a basic source of hydration, but nothing feels natural about almost drowning. It feels violent and foreign and so unbelievably painful.

Mom’s apologies and presents and excuses worked in the past because Lea was a child and because I didn’t want Lea to feel abandoned the way I did. She was too young to understand about Dad and too naive to understand about Mom. But I’m not a child, and Lea doesn’t need my protection anymore. And it should’ve been my turn to be the kid, not the parent. Not the understanding one, who accepts Mom’s excuses and sees the world through rose-tinted glasses. All those years I spent looking after Lea . . . Who was looking after me? Who is looking after me?

It’s a letter to Mom. I tell her how angry I am that she left me. I tell her how hurt I am that she’s more absent with one daughter than she ever was with two. I tell her she’s the reason I can’t write any lyrics, because I’m so full of rage that I can’t concentrate on anything except for how mad I am. I tell her that I need her, but I shouldn’t have to tell her that—she should just know. I tell her I resent her for never realizing how badly I needed to be a child now and then, instead of always looking after Lea. I tell her I’ll probably never forgive her for choosing to grieve alone, without

...more

“Everyone wants to go to college. It’s basically like high school but with less homework and more freedom.”

I touch on this later, but no, Alice, they really don't. This is a pressure driven fantasy that's pressed on kids when there are so many avenues open to them that don't involve school, that don't involve going away, getting in debt, or whatever. You don't always have to follow The Plan.

I scowl at everyone who thinks it’s not disgusting to swap spit in the middle of a public cafeteria.

Kelly and 3 other people liked this

And she gets me—like, really gets me. I don’t feel like I have to constantly explain myself, or justify why I feel the things I feel. She doesn’t think it’s weird I’m not interested in romance or college or anything besides music.

“What’s wrong with waiting?” “It’s kind of a waste of time, no?” “No. Because I’m waiting for something.” “That sounds pretty lazy.” “Lea and I have a plan. That’s not lazy—that’s following our dreams.”

Alice represents everyone who pushes Rumi, and people like her, to be "ready" ahead of time, to fall in with the mainstream, either before they're ready or because it's the "right" thing to do at all. School or romance, there doesn't have to be a right time or even A time if you don't want there to be.

It’s scary trying to decide what I’m supposed to do with all that extra time. I mean, it could be days or months or years. What if I live to be one hundred? What if I only make it until the end of next week? Does everything in the middle become a waste, because there wasn’t enough time to finish what I’ve started? And what about things I don’t know the answers to? Like, what if I die before I ever play an instrument again? What if I die without knowing what my favorite hot dog topping is? What if I die before I ever have sex? Or before I figure out if I ever want to have sex?

The potential of life is terrifying. There's the possibility of depth or of shallowness. You could have forever or today. The not knowing can be paralyzing.

It’s piano music today. It sounds like salt and whispers and abandoned lighthouses.

The dimensions Akemi gives music go beyond sound. They encompass multiple senses and envelop the reader, deepening the experience that Rumi is having and that we are sharing at the same time.

Kelly and 2 other people liked this

At the end of the song, I barely take a breath. My fingers jump into the next piece in my repertoire, like a playlist from my memory that can’t be stopped.

Muscle memory is a beautiful and terrifying thing. So many things can lay dormant in the depths of your body, your arms legs fingers, waiting for the first step before it begins the cascade of movement that leads to everything.

I hurt people, even when I don’t always mean to. I don’t want to hurt anyone the way Dad hurt us—the way he hurt Mom. But I can’t help it. Maybe I’m too much like him. Because I say things and do things and I never know how to take them back. Sometimes I don’t even know I want to, until too much time has passed. It’s hard to apologize right away. It’s even harder to apologize later on, because then you have to relive arguments all over again.

I don’t tell him that my eyes wandered around the room. I don’t tell him that I saw the picture frames on the wall. I don’t tell him that I saw him and his wife and a little boy. And I certainly don’t ask him what happened to the boy and why he has a son who never comes to visit. Because there are no photographs of a teenager or a young man. Just pictures of a little boy, frozen in time much too young. A child who will never grow up. Just like Lea.

Two women are singing a duet, their voices like a pair of songbirds perched in an apricot tree.

I don’t know what I’m looking for in love. I don’t even think I’m looking for love at all. I don’t see people and feel that rush of excitement Lea always described when she had a crush—the kind of excitement that leads to touching and kissing and whatever else. I just see people that might make good friends, and I’ve always been okay with that.

I said I’d never miss anything as much as I miss Lea, and I won’t for as long as I live, but maybe I can miss something in a different way. Maybe hearts have layers, and the layer that misses Lea is simply different from the layer that misses creating songs.

Because music is a carnival at night, lit up by a thousand stars and bursting with luminescent colors and magical illusions.

This ukulele doesn’t want to fight. It wants to lie on the beach and feel the sand in its fingers. It wants to float on a raft in the ocean, drifting off to sleep with the rise and fall of every wave. It wants to come alive at the warmest part of the day, when the sky is the most perfect blue and the sun makes the world feel like home.

I don’t want to see Mom, and Aunty Ani is Judas, as far as I’m concerned, for letting her into this house without warning me first.

I feel like I owe her more than I’m able to give her. I feel like I’m living the life she should have had—the life she deserved so much more than me.

I don’t understand it. I don’t understand willingly throwing away four entire years of your life just because you don’t want to fight with your dad about it. Or because you can’t think of anything better to do. I don’t know how to make decisions because I’m terrified of making the wrong choice, but to make a choice I don’t even want? Or to make a choice that requires years of commitment I can’t take back? It’s ridiculous. Kai is walking into a prison sentence and he isn’t even flinching.

“Well, if you ever like play it fo’ someone—you know, fo’ a fresh set of ears or something—I’m here. I mean, we don’t even have to leave our houses. You could open your window and I can listen from across the yard.”

Kai's openness to Rumi as a friend is so kind & soothing. As difficult as she's been while going through her grief, he's been supportive of her working through things, even if it means in something like listening to her music from across the yard.

And I kiss him back because that’s what I’m supposed to do. Right?

Caleb said he couldn’t stop thinking about kissing me. And how I let him, because I thought I wanted him to. I thought I was supposed to want him to.

“There is nothing wrong with you, Rumi.” She shrugs. “You don’t have to like kissing Caleb. You don’t have to like kissing boys. And you know what? Maybe you don’t even have to like kissing, period. It doesn’t matter—you’re still just as normal as everyone else.”

I don’t care what people at school think about me as a person, but I do care about the fact that they might have an opinion on my sexuality before I do. It feels . . . invasive. It feels like I’m being rushed.

I try to find my words and dust them off so that they mean what I want them to. “I know what asexuality is. But there’s also demisexual and gray asexual and then romantic orientation, too—and I don’t know where I fit in. I’m not comfortable with the labels, because labels feel so final. Like I have to make up my mind right this second. Like I have to be as sure of myself as everyone else seems to be.

“Your sexuality—and how you identify—is nobody else’s business. You can change your mind, or not change your mind. Those labels exist for you, and not so that everyone else can try to force you into a box. Especially if that box is their close-minded idea of fucking normal.”

She says you swear like a sailor.” I think that’s code for “You swear like Dad,” but I don’t really care. Sometimes swearing feels good.

“I think you’re less confused than you think you are. You just need to learn how to trust yourself,”

“Michiko wen’ to da same school as me, but she was two years older. I was friends wit’ her bruddah, so we all wen’ go walk to school together. She tol’ me I was too young fo’ her, so every year on my birt’day, I would go her house fo’ ask her out on a date. “An’ even aftah I wen’ college, I still wen’ stop by her house every year, even though she was engaged to some uddah guy. Finally, one day she ask me, ‘Why you keep knocking on my door when you know I getting married to someone else?’ So den I tell her, ‘I know you no like marry dat uddah guy—you like marry me, as soon as I get old enough.’

...more

But I’m afraid if I play her guitar, she might disappear for good. I don’t know what it will mean if her guitar becomes mine—if her sound becomes mine.

I’m not ready to face the world without Lea. I’m not ready to go back to how it felt when I first came to Hawaii—so full of rage and pain.

Mom coming back into my life doesn’t change the fact that she left. It doesn’t change the fact that she wouldn’t have left if Lea had been the one to survive.

“I think the problem is I’m not sure how I feel. Maybe I’ll still join, and maybe I won’t. Just . . . be my friend too, okay? Support me no matter what I decide. No more judging my life choices and waving your dead sister card around to make me feel guilty.”

I’ll remember you in summer, when the bluest sky turns black, and the stars form words across the sky, saying you aren’t coming back.

it feels like I’ve been avoiding Aunty Ani for a long time. Maybe too long. It’s not her fault Lea died. It’s not her fault Mom left. I need to stop punishing her for events she had no control over.

“I’m not angry at you for asking,” I say, staring at the table. “But I’m angry at her for thinking it’s okay to talk now, after she left me for weeks to deal with all of this on my own.

It’s not that I think she didn’t love us both, because I know she did. But Mom never remembered to care about me the way she cared about Lea. Because Lea was her baby, and I was her helper—the one who took care of Lea when Mom couldn’t be around.

Because sometimes that’s important—asking fo’ help. There’s no shame in saying, ‘I can’t do this alone.’ There’s no shame in saying, ‘I’m not okay.’

“That’s not an excuse. She should’ve told me. She should’ve tried harder. Because I’m not okay either. I can’t do this alone. Or at least I didn’t want to, but there was no other option for me. Because Mom never gave me one.”

I don't blame Mom for needing help. Recognizing she needed to be in a facility like that might have been the right move for her, but sending Rumi away with no explanation was not. This is the damage it caused.

Grief is a monster—not everyone gets out alive, and those who do might only survive in pieces.

You feel sick, you go see one doctor. Dat’s da rules,” Mr. Watanabe says finally. I frown. “Mom’s not sick.” He grunts. “Her mind feel sick, eh? Same same.”

Mental illness can be hard to understand at the best of times & Rumi's position is not one of those times. If she weren't in the position of dealing with her own survivor's guilt, feeling of abandonment, and so forth, maybe she wouldn't be making statements like this that make it sound like mental illness isn't the same as physical. Mr. Watanabe's attitude, never taking guff from her, points out that, really, it is and while her anger, her grief, is justified, the whole thing is maybe just too complicated to have black and white, Rumi & Mom.

“Grieving Lea was more important to her than making sure I was okay.”

Maybe this wasn't all about grieving Lea. A lot of it, sure, no doubt, but what would Mom have been like if she stayed? Grief, depression, guilt, what might that have been like as a parent staying behind with Rumi? All of those things together are a recipe for a mess and grieving for Lea is one part, but protecting Rumi from seeing her mother succumb to all of that might have been another part. Which is worse, the anger and abandonment or whatever she would have felt if she'd seen what might have happened if her mom had stayed and withered?

“Not so easy, you know, trying fo’ talk story wit’ everybody and trying fo’ act normal when nothing feels like normal—never mind trying fo’ take care of anuddah person. Sometimes it’s real hard jus’ fo’ get out of bed.”

The truth is, I never really felt like one of Mom’s kids. I felt like her helper—I felt like a second parent for Lea.

if Mom’s around more, everything is going to change. Lea will have her real mother back, and Mom will get to be a parent to Lea, who’s still young enough to need one. I don’t know where I’ll fit in our family.