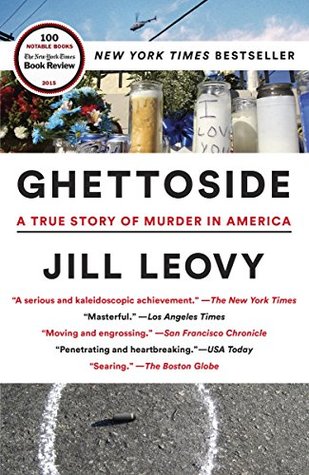

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Jill Leovy

Read between

February 4 - February 21, 2015

In 1993, black men in their early twenties in Los Angeles County died by homicide at a rate of 368 per 100,000 population, similar to the per capita rate of death for U.S. soldiers deployed to Iraq in the aftermath of the 2003 invasion.

Debts and competition over goods and women—especially women—drove many killings. But insults, snitching, drunken antics, and the classic—unwanted party guests—also were common homicide motives. Small conflicts divided people into hostile camps

“Be careful,” he told Skaggs. “Because nothing else matters after working murders.”

Underrated part of this book is the police procedural aspect. Really incredible stuff for anyone who has watched shows like The Wire, etc.

Legal scholar Randall Kennedy was a lonely voice among his peers when he asserted that “the principal injury suffered by African-Americans in relation to criminal matters is not overenforcement but underenforcement of the laws.”

The killing of a human being anywhere is like a rock thrown in a pond. Bitter waves emanate outward, washing over an ever-wider circle of friends, colleagues, and acquaintances, finally lapping against those distant from the impact point, friends of friends, old classmates, all, to some measure, sickened by the taint of this news—murder, so awful, so unbelievable—no degree of separation big enough to neutralize its poison.

Formal law impinged on them only for purposes of control, not protection. Small crimes were crushed, big ones indulged—so long as the victims were black.

It might not seem self-evident that impunity for white violence against blacks would engender black-on-black murder. But when people are stripped of legal protection and placed in desperate straits, they are more, not less, likely to turn on each other.

This set up the great clash of the late twentieth century. A flood of black migrants, schooled by the lawless South, swept into cities such as Los Angeles. They brought with them their high homicide rates and their tendency for legal self-help.

There was possibly another reason suspects submitted to being interrogated: it was interesting. Few people can resist talking about something that really interests them with someone who shares that interest.

A black assailant looking to kill a gang rival is looking, before anything else, for another black male. This was the fundamental fact of Bryant Tennelle’s death.

“Just say what happened” was another of La Barbera’s credos from the old Southeast homicide squad. Skaggs and Tennelle believed so wholeheartedly in this description of their role as law enforcement officers that they did not see how anyone could be mad at them.

“As homicide creeps up, witness cooperation drops off,” he said. A feedback loop exists between murder rates and ambient fear;

He believed in his heart that violence comes first—that law is built on the state’s response to violence—and that responding was better than preventing. It was more true to the spirit of the law—and in the long run, more effective.

But the dark swath of misery it had cut across generations of black Americans was a shadow thrown on the wall, a shape magnified many times the size of its source because of a refusal to see the black homicide problem for what it was: a problem of human suffering caused by the absence of a state monopoly on violence.

As we have seen, autonomy counters homicide.

"F*** that, I LIVE in LA!"