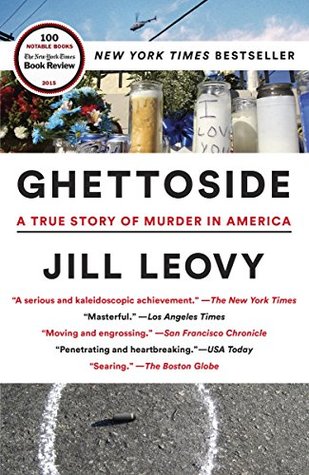

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Skaggs’s father had always said little about his choices. Now he had just one comment for the son who set out to follow his own path to homicide work: “Be careful,” he told Skaggs. “Because nothing else matters after working murders.”

Death penalty studies, for example, have found that the race of defendants matters less than the race of victims. People who kill whites are more likely to be sentenced to death; people who kill blacks get lighter penalties.

In contrast to wealthier neighborhoods, where most people worked at day jobs and neighbors knew each other in passing or not at all, the unemployed people of these places were home all day, hanging out together, confined to a few blocks. It lent the constant calls for “the community to come together” a touch of absurdity. Watts already had more togetherness than most Americans could tolerate.

“Choices” rhetoric helped officers ascribe the violence of Watts to individuals, and thus avoid explanations that felt like group generalizations about black people. But talk of “choices” also inevitably raised questions of blame. And since blame also served as a satisfying distancing mechanism, officers ended by blaming not just suspects but victims for the “choices” they’d made.

This was exactly the point: getting rid of people. Seldom was it put this way. But one of the primary reasons to have a legal system is to take certain people out of the picture.

Skaggs couldn’t understand why suspects confessed. But La Barbera, who ascribed sentimental motives to everyone—even murderers—had a theory. He believed it was the burden of guilt. Murder, he suggested, had a kind of existential weight; one had to be very hardened indeed not to be bested by it.