More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 26 - April 30, 2024

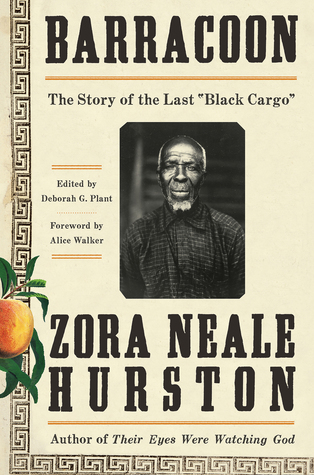

Those who love us never leave us alone with our grief. At the moment they show us our wound, they reveal they have the medicine. Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” is a perfect example of this.

Over a period of three months, Hurston visited with Kossola. She brought Georgia peaches, Virginia hams, late-summer watermelons, and Bee Brand insect powder. The offerings were as much a currency to facilitate their blossoming friendship as a means to encourage Kossola’s reminiscences. Much of his life was “a sequence of separations.”3 Sweet things can be palliative. Kossola trusted Hurston to tell his story and transmit it to the world. Others had interviewed Kossola and had written pieces that focused on him or more generally on the community of survivors at Africatown.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the Atlantic world had already penetrated the African hinterland. And although Britain had abolished the international trafficking of African peoples, or what is typically referred to as “the trans-Atlantic slave trade,” in 1807, and although the United States had followed suit in 1808, European and American ships were still finding their way to ports along the West African coast to conduct what was now deemed “illegitimate trade.” Laws had been passed and treaties had been signed, but half a century later, the deportation of Africans out of Africa and into the

...more

In conspiracy with Meaher, William Foster, who built the Clotilda, outfitted the ship for transport of the “contraband cargo.” In July 1860, he navigated toward the Bight of Benin. After six weeks of surviving storms and avoiding being overtaken by ships patrolling the waters, Foster anchored the Clotilda at the port of Ouidah.

Under the pretext of having been insulted when the king of Bantè refused to yield to Glèlè’s demands for corn and cattle, Glèlè sacked the town. Kossola described to Hurston the mayhem that ensued in the predawn raid when his townspeople awoke to Dahomey’s female warriors, who slaughtered them in their daze.

Hurston.10 Along with a host of others taken as captives by the Dahomian warriors, the survivors of the Bantè massacre were “yoked by forked sticks and tied in a chain,” then marched to the stockades at Abomey.11 After three days, they were incarcerated in the barracoons at Ouidah, near the Bight of Benin.

Charlotte Mason considered herself not only a patron to black writers and artists but also a guardian of black folklore. She believed it her duty to protect it from those whites who, having “no more interesting things to investigate among themselves,” were grabbing “in every direction material that by right belongs entirely to another race.”

There seems to be a note of disappointment in the historian Sylviane Diouf’s revelation that Hurston submitted Barracoon to various publishers, “but it never found a taker, and has still not been published.”19 Hurston’s manuscript is an invaluable historical document, as Diouf points out, and an extraordinary literary achievement as well, despite the fact that it found no takers during her lifetime.

Three spellings of his nation are found: Attako, Taccou, and Taccow. But Lewis’s pronunciation is probably correct. Therefore, I have used Takkoi throughout the work.

All the talk, printed and spoken, has had to do with ships and rations; with sail and weather; with ruses and piracy and balls between wind and water; with native kings and bargains sharp and sinful on both sides; with tribal wars and slave factories and red massacres and all the machinations necessary to stock a barracoon with African youth on the first leg of their journey from humanity to cattle; with storing and feeding and starvation and suffocation and pestilence and death; with slave ship stenches and mutinies of crew and cargo; with the jettying of cargoes before the guns of British

...more

All these words from the seller, but not one word from the sold. The Kings and Captains whose words moved ships. But not one word from the cargo. The thoughts of the “black ivory,” the “coin of Africa,” had no market value.

The four men responsible for this last deal in human flesh, before the surrender of Lee at Appomattox should end the 364 years of Western slave trading, were the three Meaher brothers and one Captain [William “Bill”] Foster. Jim, Tim, and Burns Meaher were natives of Maine. They had a mill and shipyard on the Alabama River at the mouth of Chickasabogue Creek (now called Three-Mile Creek) where they built swift vessels for blockade running, filibustering expeditions, and river trade. Captain Foster was associated with the Meahers in business. He was “born in Nova Scotia of English parents.”

Foster had a crew of Yankee sailors and sailed directly for Whydah [Ouidah], the slave port of Dahomey. The Clotilda slipped away from Mobile as secretly as possible so as not to arouse the curiosity of the Government.

The ceremonies over, Foster had “little trouble in procuring a cargo.” The barracoons at Whydah were overflowing. “[I]t had long been a part of the traders’ policy to instigate the tribes against each other,” so that plenty of prisoners would be taken and “in this manner keep the markets stocked. News of the trade was often published in the papers.” An excerpt from the Mobile Register of November 9, 1858, said: “‘From the West coast of Africa we have advice dated September 21st. The quarreling of the tribes on Sierra Leone River rendered the aspect of things very unsatisfactory.’”

Inciting was no longer necessary in Dahomey. The King of Dahomey had long ago concentrated all his resources on the providing of slaves for the foreign market. There was “a brisk trade in slaves at from fifty to sixty dollars apiece at Whydah. Immense numbers of Negroes were collected along the coast for export.”

“The Clotilde was taken directly to Twelve-Mile Island—a lonely, weird place by night.” There Captain Foster and the Meahers awaited the R. B. Taney, “named for Chief Justice Tainey” of the Dred Scott decision fame. Some say it was the June instead of the Taney.23 “[L]ights were smothered, and in the darkness quickly and quietly” the captives were transferred from the Clotilda “to the steamboat [and] taken up the Alabama River to John Dabney’s plantation below Mount Vernon.” They were landed the next day, and left in charge of the slave, James Dennison.

They were placed aboard the tug” and carried to Mobile. One of the Meahers bought them tickets “and saw that they boarded a train for the North. The Clotilde was scuttled and fired, Captain Foster himself placed seven cords of light wood upon her. Her hull still lies in the marsh at the mouth of Bayou Corne and may be seen at low tide. Foster afterwards regretted her destruction as she was worth more than the ten Africans given him by the Meahers as his booty.”

fined heavily for bringing in the Africans.29 The village that these Africans built after freedom came they called “African Town.” The town is now called Plateau, Alabama. The new name was bestowed upon it by the Mobile and Birmingham Railroad (now a part of the Southern Railroad System) built through [the town]. But still its dominant tone is African.

begin to dance. Dey lead de murderer out into de center of de square. De insibidi he dance. (Gesture.) And as he dance, he watch de eye of de king, an’ de eye of all de chiefs. One man will give him de sign. Nobody know which one will give de sign. Dey ’cide dat when dey was whispering together. “Derefore de executioner dance until he get de sign of de hand. Den he dance up to de murderer and touch his breast with the point of de machete. He dance away again an’ de next time he touch de man’s neck wid his knife. The third time dat he touch de man, other men rush out and seize the murderer an’

...more

people and make his own crops.’ “De king of Dahomey doan lak dat message, but Akia’on so strong, he ’fraid to come make war. So he wait. (See note 2.)2 “De king of Dahomey, you know, he got very rich ketchin slaves. He keep his army all de time making raids to grabee people to sell so de people of Dahomey doan have no time to raise gardens an’ make food for deyselves. (See note 3

Dey ketch people and dey saw de neck lak dis wid de knife den dey twist de head so and it come off de neck. Oh Lor’, Lor’! “I see de people gittee kill so fast! De old ones dey try run ’way from de house but dey dead by de door, and de women soldiers got dey head. Oh, Lor’!” Cudjo wept sorrowfully and crossed his arms on his breast with the fingers touching his shoulders. His mouth and eyes wide-open as if he still saw the gruesome spectacle. “Everybody dey run to de gates so dey kin hide deyself in de bush, you unnerstand me. Some never reachee de gate. De women soldier ketchee de young ones

...more

“We stay dere not many days, den dey march us to esoku (the sea). We passee a place call Budigree (Badigri) den we come in de place call Dwhydah. (It is called Whydah by the whites, but Dwhydah is the Nigerian pronunciation of the place.)

“But dey come and tie us in de line and lead us round de big white house. Den we see so many ships in de sea. Cudjo see many white men, too. Dey talking wid de officers of de Dahomey. We see de white man dat buy us. When he see us ready he say goodbye to de chief and gittee in his hammock and dey carry him cross de river. We walk behind and wade de water. It come up to de neck and Cudjo think once he goin’ drown, but nobody drown and we come on de land by de sea. De shore it full of boats of de Many-costs.

“When we ready to leave de Kroo boat and go in de ship, de Many-costs snatch our country cloth off us. We try save our clothes, we ain’ used to be without no clothes on. But dey snatch all off us. Dey say, ‘You get plenty clothes where you goin’.’ Oh Lor’, I so shame! We come in de ’Merica soil naked and de people say we naked savage. Dey say we doan wear no clothes. Dey doan know de Many-costs snatch our clothes ’way from us.

“Cap’n Tim and Cap’n Burns Meaher workee dey folks hard. Dey got overseer wid de whip. One man try whippee one my country women and dey all jump on him and takee de whip ’way from him and lashee him wid it. He doan never try whip Affican women no mo’.

“When we at de plantation on Sunday we so glad we ain’ gottee no work to do. So we dance lak in de Afficky soil. De American colored folks, you unnerstand me, dey say we savage and den dey laugh at us and doan come say nothin’ to us. But Free George, you unnerstand me, he a colored man doan belong to nobody. His wife, you unnerstand me, she been free long time. So she cook for a Creole man and buy George ’cause she marry wid him. Free George, he come to us and tell us not to dance on Sunday. Den he tell us whut Sunday is. We doan know whut it is before. Nobody in Afficky soil doan tell us

...more

“Know how we gittee free? Cudjo tellee you dat. De boat I on, it in de Mobile. We all on dere to go in de Montgomery, but Cap’n Jim Meaher, he not on de boat dat day. Cudjo doan know (why). I doan forgit. It April 12, 1865. De Yankee soldiers dey come down to de boat and eatee de mulberries off de trees close to de boat, you unnerstand me. Den dey see us on de boat and dey say ‘Y’all can’t stay dere no mo’. You free, you doan b’long to nobody no mo’.’ Oh, Lor’! I so glad. We astee de soldiers where we goin’? Dey say dey doan know. Dey told us to go where we feel lak goin’, we ain’ no mo’

...more

“I tell him, ‘Cap’n Tim, I grieve for my home.’ “He say, ‘But you got a good home, Cudjo.’ “Cudjo say, ‘Cap’n Tim, how big is de Mobile?’ “‘I doan know, Cudjo, I’ve never been to de four corners.’ “‘Well, if you give Cudjo all de Mobile, dat railroad, and all de banks, Cudjo doan want it ’cause it ain’ home. Cap’n Tim, you brought us from our country where we had lan’. You made us slave. Now dey make us free but we ain’ got no country and we ain’ got no lan’! Why doan you give us piece dis land so we kin buildee ourself a home?’ “Cap’n jump on his feet and say, ‘Fool do you think I goin’ give

...more

“One day Cudjo say to her, ‘I likee you to be my wife. I ain’ got nobody.’ “She say, ‘Whut you want wid me?’ “‘I wantee marry you.’ “‘You think if I be yo’ wife you kin take keer me?’ “‘Yeah, I kin work for you. I ain’ goin’ to beat you.’ “I didn’t say no more.

“Oh, Lor’! I love my chillun so much! I try so hard be good to our chillun. My baby, Seely, de only girl I got, she tookee sick in de bed. Oh, Lor’! I do anything to save her. We gittee de doctor. We gittee all de medicine he tellee us tuh git. Oh, Lor’. I pray, I tell de Lor’ I do anything to save my baby life. She ain’ but fifteen year old. But she die. Oh, Lor’! Look on de gravestone and see whut it say. August de 5th, 1893. She born 1878. She doan have no time to live befo’ she die. Her mama take it so hard. I try tellee her not to cry, but I cry too.

“Nine year we hurtee inside ’bout our baby. Den we git hurtee again. Somebody call hisself a deputy sheriff kill de baby boy now. (Over)1 “He say he de law, but he doan come ’rest him. If my boy done something wrong, it his place come ’rest him lak a man. If he mad wid my Cudjo ’bout something den he oughter come fight him face to face lak a man. He doan come ’rest him lak no sheriff and he doan come fight him lak no man. He have words wid my boy, but he skeered face him. Derefo’, you unnerstand me, he hidee hisself in de butcher wagon and when it gittee to my boy’s store, Cudjo walk straight

...more

“It only nine year since my girl die. Look lak I still hear de bell toll for her, when it toll again for my Fish-ee-ton. My po’ Affican boy dat doan never see Afficky soil.”

“I doan go nexy day, but I send David. De lawyer say dat too soon. Come back nexy week. Well, I send and I send, but Cudjo doan gittee no money. In de 1904 de yellow fever come in de Mobile and lawyer Clarke take his wife and chillun and gittee on de train to run in de New York ’way from de fever, but he never gittee in de North. He die on de way. Cudjo never know whut come of de money. It always a hidden mystery how come I not killed when de train it standing over me. I thank God I alive today. “De people see I ain’ able to work no mo’, so dey make me de sexton of de church.”

He want to do something. But I ain’ hold no malice. De Bible say not. Poe-lee say in Afficky soil it ain’ lak in de Americky. He ain’ been in de Afficky, you unnerstand me, but he hear what we tellee him and he think dat better dan where he at. Me and his mama try to talk to him and make him satisfy, but he doan want hear nothin. He say when he a boy, dey (the American Negro children) fight him and say he a savage. When he gittee a man dey cheat him. De train hurtee his papa and doan pay him. His brothers gittee kill. He doan laugh no mo’. “Well, after while, you unnerstand me, one day he say

...more

“De nexy week my wife lef’ me. Cudjo doan know. She ain’ been sick, but she die. She doan want to leave me. She cry ’cause she doan want me be lonesome. But she leave me and go where her chillun. Oh Lor’! Lor’! De wife she de eyes to de man’s soul. How kin I see now, when I ain’ gottee de eyes no mo’?

Hurston was a collector of folklore. However, the folklore she was “brought up on” contradicted the folklore she was collecting from Kossola. Moreover, “all that this Cudjo told me,” Hurston mused, “was verified from other historical sources.”25 Harlem Renaissance pundits and artists like Zora Neale Hurston were wrestling with the identity of “the Negro.” They had reclaimed the image of black people and asserted the value of black culture (vis-à-vis white people and Anglo American culture). There was a decided movement to do away with the image of “the Old Negro” and usher in “the New Negro,”

...more

The African diaspora in the Americas represents the largest forced migration of a people in the history of the world. According to Paul Lovejoy, the estimated number of Africans caught in the dragnet of slavery between 1450 and 1900 was 12,817,000.34 The

As Sylviane Diouf points out, “Of the dozen deported Africans who left testimonies of their lives, only [Olaudah] Equiano, [Mahommah Gardo] Baquaqua, and [Ottobah] Cugoano referred to the Middle Passage.”

Maafa is a Ki-Swahili term that means disaster and the human response to it.40 The term refers to the disruption and uprooting of the lives of African peoples and the commercial exploitation of the African continent from the fifteenth century to the era of Western globalization in the twenty-first century.

And in postbellum America he was subject to the exploitation of his labor and the vagaries of the law, just as he was in antebellum America. He remained confounded by this cruel treatment for the rest of his life. Kossola’s experience was not anomalous. It is representative of the reality of African American people who have been grappling for a sense of sovereignty over their own bodies ever since slavery was institutionalized.

The American Dream is a major theme in the narrative of racial difference. The shadow side of that dream, which is not talked about, entails the plundering of racial “Others.” It was this dreaming that inspired both William Foster and Tim Meaher to flout the law of the US Constitution, steal 110 Africans from their homes, and smuggle them up the Mobile River and into bondage. Though Foster and Meaher were charged with piracy, neither was convicted of any crime. No one was held responsible for the theft of Kossola and his companions and their exploitation in America. Of the thousands of

...more

“You made us slave,” Kossola told Meaher. “Now dey make us free but we ain’ got no country and we ain’ got no lan’. Why doan you give us piece dis land so we kin buildee ourself a home?”43 Meaher’s response was one of indignation. “Fool do you think I goin’ give you property on top of property? I tookee good keer my slaves in slavery and derefo’ I doan owe dem nothing? You doan belong to me now, why must I give you my lan’?”44 Kossola and the others rented the land until they were able to buy it from the Meahers and other landowners. The parcels they bought became Africatown, which was

...more

Although some African Americans were numbered among them as spouses and founders, Africatown “was not conceived of as a settlement for “‘blacks,’ but for Africans.”45 Africatown was their statement about who they were, and it was a haven from white supremacy and the ostracism of black Americans.

“On January 16, 1959, Zora Neale Hurston, suffering from the effects of a stroke and writing painfully in longhand, composed a letter to the ‘editorial department’ of Harper & Brothers inquiring if they would be interested in seeing ‘the book I am laboring upon at the present—a life of Herod the Great.’ One year and twelve days later, Zora Neale Hurston died without funds to provide for her burial, a resident of the St. Lucie County, Florida, Welfare Home. She lies today in an unmarked grave in a segregated cemetery in Fort Pierce, Florida, a resting place generally symbolic of the black

...more

Barnard graduate, author of four novels, two books of folklore, one volume of autobiography, the most important collector of Afro-American folklore in America, reduced by poverty and circumstance to seek a publisher by unsolicited mail.” —Robert

She shows us a picture of her father and mother and says that her father was Joe Clarke’s brother. Joe Clarke, as every Zora Hurston reader knows, was the first mayor of Eatonville; his fictional counterpart is Jody Starks of Their Eyes Were Watching God. We also get directions to where Joe Clarke’s store was—where Club Eaton is now. Club Eaton, a long orange-beige nightspot we had seen on the main road, is apparently famous for the good times in it regularly had by all.

“Well, I can tell you this: I have lived in Eatonville all my life and I’ve been in the governing of this town. I’ve been everything but Mayor and I’ve been assistant Mayor. Eatonville was and is an all-black town. We have our own police department, post office, and town hall. Our own school and good teachers. Do I need integration?

I think of the letter Roy Wilkins wrote to a black newspaper blasting Zora Neale for her lack of enthusiasm about the integration of schools. I wonder if he knew the experience of Eatonville she was coming from. Not many black people in America have come from a self-contained, all-black community where loyalty and unity are taken for granted. A place where black pride is nothing new.

She’s in the old cemetery, the Garden of the Heavenly Rest, on Seventeenth Street. Just when you go in the gate there’s a circle, and she’s buried right in the middle of it. Hers is the only grave in that circle—because people don’t bury in that cemetery any more.”

“And could you tell me something else? You see, I never met my aunt. When she died I was still a junior in high school. But could you tell me what she died of, and what kind of funeral she had?” “I don’t know exactly what she died of,” Mrs. Patterson says, “I know she didn’t have any money. Folks took up a collection to bury her. . . . I believe she died of malnutrition.” “Malnutrition?” Outside, in the blistering sun, I lean my head against Charlotte’s even more blistering cartop. The sting of the hot metal only intensifies my anger. “Malnutrition?” I manage to mutter. “Hell, our condition

...more