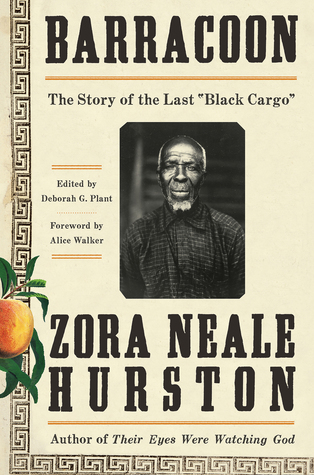

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

June 6 - June 9, 2020

The term “barracoon” describes the structures used to detain Africans who would be sold and exported to Europe or the Americas.

On December 14, 1927, Zora Neale Hurston took the 3:40 p.m. train from Penn Station, New York, to Mobile, to conduct a series of interviews with the last known surviving African of the last American slaver—the Clotilda. His name was Kossola, but he was called Cudjo Lewis.

Oluale Kossola had survived capture at the hands of Dahomian warriors, the barracoons at Whydah (Ouidah), and the Middle Passage. He had been enslaved, he had lived through the Civil War and the largely un-Reconstructed South, and he had endured the rule of Jim Crow. He had experienced the dawn of a new millennium that included World War I and the Great Depression. Within the magnitude of world events swirled the momentous events of Kossola’s own personal world.

As with the other interviews, Kossola hoped the story he entrusted to Hurston would reach his people, for whom he was still lonely. The disconnection he experienced was a source of continuous distress.

Kossola was born circa 1841, in the town of Bantè, the home to the Isha subgroup of the Yoruba people of West Africa.

At age nineteen, Kossola was undergoing initiation for marriage. But these rites would never be realized. It was 1860, and the world Kossola knew was coming to an abrupt end.

although Britain had abolished the international trafficking of African peoples, or what is typically referred to as “the trans-Atlantic slave trade,” in 1807, and although the United States had followed suit in 1808, European and American ships were still finding their way to ports along the West African coast to conduct what was now deemed “illegitimate trade.”

From 1801 to 1866, an estimated 3,873,600 Africans were exchanged for gold, guns, and other European and American merchandise.

1931. On April 18, she was enthusiastic: “At last ‘Barracoon’ is ready for your eyes.”

“The Viking press again asks for the Life of Kossula, but in language rather than dialect.

The dialect was a vital and authenticating feature of the narrative. Hurston would not submit to such revision. Perhaps, as Langston Hughes wrote in The Big Sea, the Negro was “no longer in vogue,” and publishers like Boni and Viking were unwilling to take risks on “Negro material” during the Great Depression.18

it found no takers during her lifetime.

Hurston transcribes Kossola’s story, using his vernacular diction, spelling his words as she hears them pronounced. Sentences follow his syntactical rhythms and maintain his idiomatic expressions and repetitive phrases. Hurston’s methods respect Kossola’s own storytelling sensibility; it is one that is “rooted ‘in African soil.’”

The story Hurston gathers is presented in such a way that she, the interlocutor, all but disappears. The narrative space she creates for Kossola’s unburdening is sacred. Rather than insert herself into the narrative as the learned and probing cultural anthropologist, the investigating ethnographer, or the authorial writer, Zora Neale Hurston, in her still listening, assumes the office of a priest. In this space, Oluale Kossola passes his story of epic proportion on to her.

Robin liked this

Preface This is the life story of Cudjo Lewis, as told by himself. It makes no attempt to be a scientific document, but on the whole he is rather accurate. If he is a little hazy as to detail after sixty-seven years, he is certainly to be pardoned.

Zora Neale Hurston April 17, 1931

Of all the millions transported from Africa to the Americas, only one man is left. He is called Cudjo Lewis and is living at present at Plateau, Alabama, a suburb of Mobile. This is the story of this Cudjo.

the story of the last load of slaves brought into the United States.

Whydah [Ouidah], the slave port of Dahomey.

The only man on earth who has in his heart the memory of his African home; the horrors of a slave raid; the barracoon; the Lenten tones of slavery; and who has sixty-seven years of freedom in a foreign land behind him.