More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 19 - February 19, 2023

But the inescapable fact that stuck in my craw, was: my people had sold me and the white people had bought me. . . . It impressed upon me the universal nature of greed and glory. —Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

Barracoon: The Spanish word barracoon translates as “barracks” and is derived from barraca, which means “hut,” and is associated with the Portugese word barracão, which means “shed.” The term “barracoon” describes the structures used to detain Africans who would be sold and exported to Europe or the Americas. These structures, sometimes also referred to as factories, stockades, corrals, and holding pens, were built near the coast. They could be as insubstantial as a “slave shed” or as fortified as a “slave house” or “slave castle,” wherein Africans were forced into the cells of dungeons

...more

On December 14, 1927, Zora Neale Hurston took the 3:40 p.m. train from Penn Station, New York, to Mobile, to conduct a series of interviews with the last known surviving African of the last American slaver—the Clotilda. His name was Kossola, but he was called Cudjo Lewis. He was held as a slave for five and a half years in Plateau-Magazine Point, Alabama, from 1860 until Union soldiers told him he was free. Kossola lived out the rest of his life in Africatown (Plateau).1 Hurston’s trip south was a continuation of the field trip expedition she had initiated the previous year. Oluale Kossola had

...more

Over a period of three months, Hurston visited with Kossola. She brought Georgia peaches, Virginia hams, late-summer watermelons, and Bee Brand insect powder. The offerings were as much a currency to facilitate their blossoming friendship as a means to encourage Kossola’s reminiscences. Much of his life was “a sequence of separations.”3 Sweet things can be palliative. Kossola trusted Hurston to tell his story and transmit it to the world. Others had interviewed Kossola and had written pieces that focused on him or more generally on the community of survivors at Africatown. But only Zora Neale

...more

ORIGINS Kossola was born circa 1841, in the town of Bantè, the home to the Isha subgroup of the Yoruba people of West Africa. He was the second child of Fondlolu, who was the second of his father’s three wives. His mother named him Kossola, meaning “I do not lose my fruits anymore” or “my children do not die any more.”4 His mother would have four more children after Kossola, and he would have twelve additional siblings from his extended family.

By age fourteen, Kossola had trained as a soldier, which entailed mastering the skills of hunting, camping, and tracking, and acquiring expertise in shooting arrows and throwing spears. This training prepared him for induction into the secret male society called oro. This society was responsible for the dispensation of justice and the security of the town. The Isha Yoruba of Bantè lived in an agricultural society and were a peaceful people. Thus, the training of young men in the art of warfare was a strategic defense against bellicose nations. At age nineteen, Kossola was undergoing initiation

...more

TRANS-ATLANTIC TRAFFICKING By the mid-nineteenth century, the Atlantic world had already penetrated the African hinterland. And although Britain had abolished the international trafficking of African peoples, or what is typically referred to as “the trans-Atlantic slave trade,” in 1807, and although the United States had followed suit in 1808, European and American ships were still finding their way to ports along the West African coast to conduct what was now deemed “illegitimate trade.” Laws had been passed and treaties had been signed, but half a century later, the deportation of Africans

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

From 1801 to 1866, an estimated 3,873,600 Africans were exchanged for gold, guns, and other European and American merchandise. Of that number, approximately 444,700 were deported from the Bight of Benin, which was controlled by Dahomey.8 During the period from 1851 to 1860, approximately 22,500 Africans were exported. And of that number, 110 were taken aboard the Clotilda at Ouidah. Kossola was among them—a transaction between Foster and King Glèlè. In 1859, King Ghezo was mortally shot while returning from one of his campaigns. His son Badohun had ascended to the throne. He was called Glèlè,

...more

Before him was a thunderous and crashing ocean that he had never seen before. Behind him was everything he called home. There in the barracoon, as there in his Alabama home, Kossola was transfixed between two worlds, fully belonging to neither.

Charlotte Mason considered herself not only a patron to black writers and artists but also a guardian of black folklore. She believed it her duty to protect it from those whites who, having “no more interesting things to investigate among themselves,” were grabbing “in every direction material that by right belongs entirely to another race.” Following the suggestions of Mason and Alain Locke, Hurston advised Kossola and his family “to avoid talking with other folklore collectors—white ones, no doubt—who he and Godmother felt ‘should be kept entirely away not only from the project in hand but

...more

Hurston’s manuscript is an invaluable historical document, as Diouf points out, and an extraordinary literary achievement as well, despite the fact that it found no takers during her lifetime. In it, Zora Neale Hurston found a way to produce a written text that maintains the orality of the spoken word. And she did so without imposing herself on the narrative, creating what some scholars classify as orature. Contrary to the literary biographer Robert Hemenway’s dismissal of Barracoon as Hurston’s re-creation of Kossola’s experience, the scholar Lynda Hill writes that “through a deliberate act

...more

As she states in her preface, “For historical data, I am indebted to the Journal of Negro History, and to the records of the Mobile Historical Society.” She reiterates this acknowledgment in her introduction and alludes to the use of other “records.” Hurston drew from Emma Langdon Roche’s Historic Sketches, but she references this work indirectly, and her citation from this book, as well as the other sources she utilized, was inconsistent. Wherever there is a question regarding her use of paraphrase and direct quotation, I have revised the passage as a direct quote and have documented it

...more

The “Door of No Return” at La Maison des Esclaves (House of Slaves) at Gorée Island in Senegal, West Africa. Above the entryway: “Lord, give my people, who have suffered so much, the strength to be great” (Joseph Ndiaye).

To Charlotte Mason My Godmother, and the one Mother of all the primitives, who with the Gods in Space is concerned about the hearts of the untaught

This is the life story of Cudjo Lewis, as told by himself. It makes no attempt to be a scientific document, but on the whole he is rather accurate. If he is a little hazy as to detail after sixty-seven years, he is certainly to be pardoned. The quotations from the works of travelers in Dahomey are set down, not to make this appear a thoroughly documented biography, but to emphasize his remarkable memory. Three spellings of his nation are found: Attako, Taccou, and Taccow. But Lewis’s pronunciation is probably correct. Therefore, I have used Takkoi throughout the work. I was sent by a woman of

...more

All these words from the seller, but not one word from the sold. The Kings and Captains whose words moved ships. But not one word from the cargo. The thoughts of the “black ivory,” the “coin of Africa,” had no market value. Africa’s ambassadors to the New World have come and worked and died, and left their spoor, but no recorded thought. Of all the millions transported from Africa to the Americas, only one man is left. He is called Cudjo Lewis and is living at present at Plateau, Alabama, a suburb of Mobile. This is the story of this Cudjo.

The only man on earth who has in his heart the memory of his African home; the horrors of a slave raid; the barracoon; the Lenten tones of slavery; and who has sixty-seven years of freedom in a foreign land behind him.

I wanted to ask that, but I want to ask you many things. I want to know who you are and how you came to be a slave, and to what part of Africa do you belong, and how you fared as a slave, and how you have managed as a free man?” Again his head was bowed for a time. When he lifted his wet face again he murmured, “Thankee Jesus! Somebody come ast about Cudjo! I want tellee somebody who I is, so maybe dey go in de Afficky soil some day and callee my name and somebody dere say, ‘Yeah, I know Kossula.’ I want you everywhere you go to tell everybody whut Cudjo say, and how come I in Americky soil

...more

“But Kossula, I want to hear about you and how you lived in Africa.” He gave me a look full of scornful pity and asked, “Where is de house where de mouse is de leader? In de Affica soil I cain tellee you ’bout de son before I tellee you ’bout de father; and derefore, you unnerstand me, I cain talk about de man who is father (et te) till I tellee you bout de man who he father to him, (et, te, te, grandfather) now, dass right ain’ it? “My grandpa, you unnerstand me, he got de great big compound. He got plenty wives and chillun. His house, it is in de center de compound. In Affica soil de house

...more

Cudjo looked out over his patch of pole-beans towards the house of his daughter-in-law. I waited for him to resume, but he just sat there not seeing me. I waited but not a sound. Presently he turned to the man sitting inside the house and said, “go fetchee me some cool water.” The man took the pail and went down the path between the rows of pole-beans to the well in the daughter-in-law’s yard. He returned and Kossula gulped down a healthy cup-full from a home-made tin cup. Then he sat and smoked his pipe in silence. Finally he seemed to discover that I was still there. Then he said brusquely,

...more

The next day about noon I was again at Kossula’s gate. I brought a gift this time. A basket of Georgia peaches. He received me kindly and began to eat the peaches at once.

There is a large peach tree in the yard that bears small but delicious clingstone peaches. They were beginning to ripen. The old man gave me one or two and put away one for each of the twins. I was shown all over the gardens. Kossula was genial but not one word about himself fell from his lips. So I went away and came again the following day. I brought another gift. A box of Bee Brand insect powder to burn in the house to drive out all the mosquitoes.

Kossula got that remote look in his eyes and I knew he had withdrawn within himself. I arose to go. “You going very soon today,” he commented. “Yes,” I said, “I don’t want to wear out my welcome. I want you to let me come and talk with you again.” “Oh, I doan keer you come see me. Cudjo lak have comp’ny. Now I go water de tater vines. You see kin you find ripe peach on de tree and gittee some take home.” I put the ladder in the tree and climbed up in easy reach of a cluster of pink peaches. He saw me to the gate and graciously said goodbye. “Doan come back till de nexy week, now I need choppee

...more

In the six days between my visits to Kossula I worried a little lest he deny himself to me. I had secured two Virginia hams on my trip south and when I appeared before him the following Thursday, I brought him one. He was delighted beyond his vocabulary, but I read his face and it was more than enough. The ham was for him. For us I brought a huge watermelon, right off the ice, so we cut it in half and we just ate from heart to rind as far as we were able.

Kossula ceased speaking and looked pointedly at his melon rind. There was still lots of good red meat and a quart or two of juice. I looked at mine. I had more meat left than Kossula had. Nothing was left of the first installment, but a pleasant memory. So we lifted the half-rinds to our knees and started all over again. The sun was still hot so we did the job leisurely. Watermelon halves having ends like everything else, and a thorough watermelon eating being what it is, a long over-stuffed silence fell on us. When I was able to speak, somehow the name juju came into my mind, so I asked

...more

“When I see de king dead, I try to ’scape from de soldiers. I try to make it to de bush, but all soldiers over-take me befo’ I git dere. O Lor’, Lor’! When I think ’bout dat time I try not to cry no mo’. My eyes dey stop cryin’ but de tears runnee down inside me all de time. When de men pull me wid dem I call my mama name. I doan know where she is. I no see none my family. I doan know where dey is. I beg de men to let me go findee my folks. De soldiers say dey got no ears for cryin’. De king of Dahomey come to hunt slave to sell. So dey tie me in de line wid de rest.

Kossula was no longer on the porch with me. He was squatting about that fire in Dahomey. His face was twitching in abysmal pain. It was a horror mask. He had forgotten that I was there. He was thinking aloud and gazing into the dead faces in the smoke. His agony was so acute that he became inarticulate. He never noticed my preparation to leave him. So I slipped away as quietly as possible and left him with his smoke pictures.

‘You get plenty clothes where you goin’.’ Oh Lor’, I so shame! We come in de ’Merica soil naked and de people say we naked savage. Dey say we doan wear no clothes. Dey doan know de Many-costs snatch our clothes ’way from us. (See note 7.)6 “Soon we git in de ship dey make us lay down in de dark. We stay dere thirteen days. Dey doan give us much to eat. Me so thirst! Dey give us a little bit of water twice a day. Oh Lor’, Lor’, we so thirst! De water taste sour. (Vinegar was usually added to the water to prevent scurvy—Canot.)7 “On de thirteenth day dey fetchee us on de deck. We so weak we ain’

...more

We cry for home. We took away from our people. We seventy days cross de water from de Affica soil, and now dey part us from one ’nother. Derefore we cry. We cain help but cry. So we sing: “‘Eh, yea ai yeah, La nah say wu Ray ray ai yea, nah nah saho ru.’ “Our grief so heavy look lak we cain stand it. I think maybe I die in my sleep when I dream about my mama. Oh Lor’!”

Kossula sat silent for a moment. I saw the old sorrow seep away from his eyes and the present take its place. He looked about him for a moment and then said bluntly, “I tired talking now. You go home and come back. If I talkeed wid you all de time I cain makee no garden. You want know too much. You astee so many questions. Dat do, dat do (that will do, etc.), go on home.” I was far from being offended. I merely said, “Well when can I come again?” “I send my grandson and letee you know, maybe tomorrow, maybe nexy week.”

“Every time de boat stopee at de landing, you unnerstand me, de overseer, de whippin’ boss, he go down de gangplank and standee on de ground. De whip stickee in his belt. He holler, ‘Hurry up, dere, you! Runnee fast! Can’t you runnee no faster dan dat? You ain’t got ’nough load! Hurry up!’ He cutee you wid de whip if you ain’ run fast ’nough to please him. If you doan git a big load, he hitee you too. Oh, Lor’! Oh, Lor’! Five year and de six months I slave. I workee so hard! Looky lak now I see all de landings. I callee all dem for you.

“When we at de plantation on Sunday we so glad we ain’ gottee no work to do. So we dance lak in de Afficky soil. De American colored folks, you unnerstand me, dey say we savage and den dey laugh at us and doan come say nothin’ to us. But Free George, you unnerstand me, he a colored man doan belong to nobody. His wife, you unnerstand me, she been free long time. So she cook for a Creole man and buy George ’cause she marry wid him. Free George, he come to us and tell us not to dance on Sunday. Den he tell us whut Sunday is. We doan know whut it is before. Nobody in Afficky soil doan tell us

...more

April 12, 1865. De Yankee soldiers dey come down to de boat and eatee de mulberries off de trees close to de boat, you unnerstand me. Den dey see us on de boat and dey say ‘Y’all can’t stay dere no mo’. You free, you doan b’long to nobody no mo’.’ Oh, Lor’! I so glad. We astee de soldiers where we goin’? Dey say dey doan know. Dey told us to go where we feel lak goin’, we ain’ no mo’ slave. “Thank de Lor’! I sho ’ppreciate dey free me. Some de men dey on de steamboat in de Montgomery and dey got to come in de Mobile and unload de cargo. Den dey free too. “We ain’ got no trunk so we makee de

...more

“We work hard and try save our money. But it too much money we need. So we think we stay here. “We see we ain’ got no ruler. Nobody to be de father to de rest. We ain’ got no king neither no chief lak in de Affica. We doan try get no king ’cause nobody among us ain’ born no king. Dey tell us nobody doan have no king in ’Merica soil. Derefo’ we make Gumpa de head. He a nobleman back in Dahomey. We ain’ mad wid him ’cause de king of Dahomey ’stroy our king and sell us to de white man. He didn’t do nothin’ ’ginst us. “Derefore we join ourselves together to live. But we say, ‘We ain’ in de Affica

...more

‘Cap’n Tim, I grieve for my home.’ “He say, ‘But you got a good home, Cudjo.’ “Cudjo say, ‘Cap’n Tim, how big is de Mobile?’ “‘I doan know, Cudjo, I’ve never been to de four corners.’ “‘Well, if you give Cudjo all de Mobile, dat railroad, and all de banks, Cudjo doan want it ’cause it ain’ home. Cap’n Tim, you brought us from our country where we had lan’. You made us slave. Now dey make us free but we ain’ got no country and we ain’ got no lan’! Why doan you give us piece dis land so we kin buildee ourself a home?’ “Cap’n jump on his feet and say, ‘Fool do you think I goin’ give you property

...more

“We call our village Affican Town. We say dat ’cause we want to go back in de Affica soil and we see we cain go. Derefo’ we makee de Affica where dey fetch us. Gumpa say, ‘My folks sell me and yo folks (Americans) buy me.’ We here and we got to stay. “Free George come help us all de time. De colored folks whut born here, dey pick at us all de time and call us ig’nant savage. But Free George de best friend de Afficans got. He tell us we ought gittee de religion and join de church. But we doan want be mixee wid de other folks what laught at us so we say we got plenty land and derefo’ we kin

...more

Oh, Lor’. I pray, I tell de Lor’ I do anything to save my baby life. She ain’ but fifteen year old. But she die. Oh, Lor’! Look on de gravestone and see whut it say. August de 5th, 1893. She born 1878. She doan have no time to live befo’ she die. Her mama take it so hard. I try tellee her not to cry, but I cry too. “Dat de first time in de Americky soil dat death find where my door is. But we from cross de water know dat he come in de ship wid us. Derefo’ when we buildee our church, we buy de ground to bury ourselves. It on de hill facin’ de church door. “We Christian people now, so we put our

...more

“He pray all he could. His mama pray. I pray so hard, but he die. I so sad I wish I could die in place of my Cudjo. Maybe, I doan pray right, you unnerstand me, ’cause he die while I was prayin’ dat de Lor’ spare my boy life. “De man dat killee my boy, he de paster of Hay Chapel in Plateau today. I try forgive him. But Cudjo think that now he got religion, he ought to come and let me know his heart done change and beg Cudjo pardon for killin’ my son. “It only nine year since my girl die. Look lak I still hear de bell toll for her, when it toll again for my Fish-ee-ton. My po’ Affican boy dat

...more

“Look lak we ain’ cry enough. We ain’ through cryin. In de November our Jimmy come home and set round lak he doan feel good so I astee him, ‘Son, you gittee sick? I doan want you runnin’ to work when you doan feel good.’ He say, ‘Papa, tain nothin’ wrong wid me. I doan feel so good.’ But de nexy day, he come home sick and we putee him in de bed. I do all I kin and his mama stay up wid him all night long. We gittee de doctor and do whut he say, but our boy die. Oh Lor’! I good to my chillun! I want dey comp’ny, but looky lak dey lonesome for one ’nother. So dey hurry go sleep together in de

...more

I had spent two months with Kossula, who is called Cudjo, trying to find the answers to my questions. Some days we ate great quantities of clingstone peaches and talked. Sometimes we ate watermelon and talked. Once it was a huge mess of steamed crabs. Sometimes we just ate. Sometimes we just talked. At other times neither was possible, he just chased me away. He wanted to work in his garden or fix his fences. He couldn’t be bothered. The present was too urgent to let the past intrude. But on the whole, he was glad to see me, and we became warm friends. At the end the bond had become strong

...more

A memory test game played by two players. One player (A) the tester, squats facing the diagram which is drawn on the ground. The other player whose memory is to be tested squats with his back to the figure. A grain of corn is placed in each of the 3 circles between the lines. Each of the lines (1, 2, 3) has a name. No 1 Ah Kinjaw Mah Kinney No 2 Ah-bah jah le fon No 3 Ah poon dacre ad meejie

Another game seems to be akin to both billiards and bowling. Three balls are racked up and the player stands off and knocks them down with seven balls in his hand. The top ball of the three must be hit last with the seventh thrown ball.

There are two pieces of iron slanting slightly upward in each inside wall of the fireplace. It is an African idea transplanted to America. They are placed there to support the racks for drying fish. Kossula smokes a great deal and tamps his pipe quite often. All of his pipes have tops that he has made himself to keep the fire from falling out as he works. The pipe lids are just another of the evidences of the primitive, the self-reliance of the people who live outside the influence of machinery. There is something in the iron pot bubbling away among the coals. We eat some of the stew and find

...more

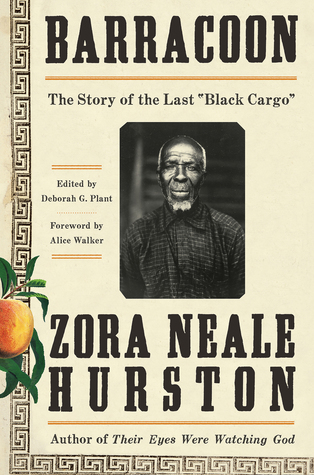

Cudjo Lewis (Oluale Kossola), in front of his home in Africatown (Plateau), Alabama, circa 1928. To have his photograph taken, Kossola dressed in his best suit and removed his shoes: “I want to look lak I in Affica, ’cause dat where I want to be.”

From February to August of 1927, Hurston conducted fieldwork in Florida and Alabama under the direction of Franz Boas, her mentor, the renowned “Father of American Anthropology.” Boas had early on approached Woodson, the “Father of Black History,” about a fellowship for Hurston, in support of the research. In accordance with their arrangements, Hurston was to collect black folk materials for Boas and scout around for undiscovered black folk artists. In addition to the gathering of historical data for Woodson, she was also to collect Kossola’s story.5

Woodson published this material as an article entitled “Communications,” in the October 1927 issue of the Journal. In the same issue, he published Hurston’s Kossola interview as “Cudjo’s Own Story of the Last African Slaver.”6 A footnote at the beginning of the article stated that as “an investigator of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History,” Zora Neale Hurston had traveled to Mobile to interview Lewis, “the only survivor of this last cargo.” The note states further, “She made some use, too, of the Voyage of Clotilde and other records of the Mobile Historical Society.”7 In

...more

“Of the sixty-seven paragraphs in Hurston’s essay,” Hemenway relates, “only eighteen are exclusively her own prose.”9 Hemenway speculates that Hurston found her interview with Kossola lacking in original material and therefore resorted to the use of Roche’s work to supplement it. He supposes, too, that Hurston, writing at the outset of her career, suffered a quandary of purpose, direction, and methodology: How, exactly, was she to introduce the world to African American folklore, which she perceived to be “the greatest cultural wealth on the continent”?10 Hemenway observed that Hurston, as one

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Nonetheless, Hemenway wondered why Hurston would risk her career and whether her use of Roche’s work was “an unconscious attempt at academic suicide.” This attempt, Hemenway concludes, “is made because of a lack of respect for the writing one has to do.” If detected and “her scientific integrity destroyed . . . Hurston’s academic career would have been finished.” She would then have been free from Boas’s admonitions and Woodson’s demands, and “the unglamorous labor” of collecting folklore.14 Is it possible, Hemenway speculates further, that footnotes referencing Roche had been included but

...more

Speculations aside, Boyd states, “Making ‘some use’ of material from another writer is completely common and acceptable. But, as Zora knew, copying another’s work, and passing it off as one’s own, is not.”20

It is possible that the submitted report may have both relieved Hurston of tedium and allowed her a boon of lore for her own purposes, thereby hitting a straight lick with a crooked stick. Or, as Lynda Marion Hill suggests in Social Rituals and the Verbal Art of Zora Neale Hurston, Hurston’s perceived professional faux pas may have been an instance of Hurston masking her emotional response to a troubling event. In 1927, Zora Neale Hurston was new. Although Hemenway may have agreed with Franz Boas that “Hurston was a ‘little too much impressed with her own accomplishments,’” it is equally true

...more