More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

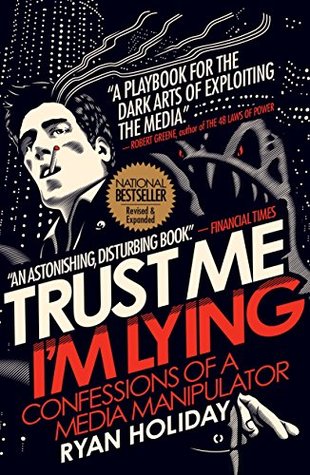

by

Ryan Holiday

Read between

July 11 - August 8, 2020

We live in a world of many hustlers, and you are the mark. The con is to build a brand off the backs of others.

Think about it: Where do people find stuff today? They find it online. This is just as true for normal people as it is for the so-called gatekeepers. If something is being chatted about on Facebook, Twitter, or Reddit, it will make its way through all other forms of media and eventually into culture itself. That’s a fact. When I figured this out early in my career in public relations, I had a thought that only a naive and destructively ambitious twenty-something would have: If I master the rules that govern blogs, I can be the master of all they determine. It was, essentially, access to a fiat

...more

One early media critic put it this way: We’re a country governed by public opinion, and public opinion is largely governed by the press, so isn’t it critical to understand what governs the press? What rules over the media, he concluded, rules over the country. In this case, what ruled over Politico literally almost ruled over everyone.

It wasn’t crazy. Blogs need things to cover. The Times has to fill a newspaper only once per day. A cable news channel has to fill twenty-four hours of programming 365 days a year. But blogs have to fill an infinite amount of space. The site that covers the most stuff wins.

Their platform accumulates real supporters who donate real time and money to the campaign. The campaign buzz is reified by the mass media, who covers and legitimizes whatever is being talked about online.

In a post explaining to publicists how they could better game bloggers like herself, Lindsay advised focusing “on a lower traffic tier with the (correct) understanding that these days, content filters up as much as it filters down, and often the smaller sites, with their ability to dig deeper into the [I]nternet and be more nimble, act as farm teams for the larger ones.”

For the sake of simplicity, though, let’s break the chain into three levels. I know these levels as one thing only: beachheads for manufacturing news. I don’t think someone could have designed a system easier to manipulate if they wanted to.

It’s a simple illusion: Create the perception that the meme already exists and all the reporter (or the music supervisor or celebrity stylist) is doing is popularizing it. They rarely bother to look past the first impressions.

websites need to see to get excited. Former Slate.com media critic Jack Shafer called such manufactured online controversy “frovocation”—a portmanteau of faux provocation. “Outrage porn” is a better term. People like getting pissed off almost as much as they like actual porn.

Picture a galley rowed by slaves and commanded by pirates. —TIM RUTTEN, LOS ANGELES TIMES, ON THE HUFFINGTON POST BUSINESS MODEL

They broke the story of Mel Gibson’s anti-Semitic outbursts during his DUI arrest. And then they got video of Michael Rich-ards’s racist onstage meltdown, posted the bruised-Rihanna police photo, and announced the news of Michael Jackson’s death.

One of Gawker’s biggest scoops early on in the race—certainly a TMZ-level story—was a collection of Tom Cruise Scientology videos.

The writings by which one can live are not the writings which themselves live, and are never those in which the writer does his best. . . . Those who have to support themselves by their pen must depend on literary drudgery, or at best on writings addressed to the multitude. —JOHN STUART MILL, AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Is the world terrible or is it awesome? Can’t these people just make up their minds? The press, Martin Amis once noted, “is more vicious than the populace.” It’s also more positive and gushy—as Upworthy is—than normal people. Why? Because it’s paid to be.

According to Berger’s study, anger has such a profound effect that one standard deviation increase in the anger rating of an article is the equivalent of spending an additional three hours as the lead story on the front page of NYTimes.com. Again, extremes in any direction have a large impact on how something will spread, but certain emotions do better than others. For instance, an equal shift in the positivity of an article is the equivalent of spending about 1.2 hours as the lead story. It’s a significant but clear difference. The angrier an article makes the reader, the better. But happy

...more

A powerful predictor of whether content will spread online is valence, or the degree of positive or negative emotion a person is made to feel. Both extremes are more desirable than anything in the middle.

“share this.” They push your buttons so you’ll press theirs. Things must be negative but not too negative. Hopelessness, despair—these drive us to do nothing. Pity, empathy—those drive us to do something, like get up from our computers to act. But anger, fear, excitement, laughter, and outrage—these drive us to spread. They drive us to do something that makes us feel as if we are doing something, when in reality we are only contributing to what is probably a superficial and utterly meaningless conversation. Online games and apps operate on the same principles and exploit the same impulses: Be

...more

dirty truth, the brilliant writer Venkatesh Rao pointed out, is that social media isn’t a set of tools to allow humans to communicate with humans. It is a set of embedding mechanisms to allow technologies to use humans to communicate with each other, in an orgy of self-organizing. . . . The Matrix had it wrong. You’re not the battery power in a global, human-enslaving AI, you are slightly more valuable. You are part of the switching circuitry.

“The weariness of the cell is the vigor of the organism.”

As Richard Greenblatt—maybe the greatest hacker who has ever lived—told Wired in 2010, “There’s a dynamic now that says, let’s format our web page so people have to push the button a lot so that they’ll see lots of ads. Basically, the people who win are those who manage to make things the most inconvenient for you.”

influence of the masses, but that didn’t spare it from corruption from the top. As the character Philip Marlowe observed in Raymond Chandler’s novel The Long Goodbye: Newspapers are owned and published by rich men. Rich men all belong to the same club. Sure, there’s competition—hard tough competition for circulation, for newsbeats, for exclusive stories. Just so long as it doesn’t damage the prestige and privilege and position of the owners. This was incisive media criticism (in fiction, no less) that was later echoed with damning evidence by theorists such as Noam Chomsky and Ben Bagdikian. A

...more

Card understood that it is incredibly difficult to interpret silence in a constructive way. Warnock’s Dilemma, for its part, poses several interpretations:

“He lies like a newspaper” was a common midnineteenth-century expression about people you couldn’t trust.

Factual errors are only one type of error—perhaps the least important kind. A story is made of facts, and it is the concrescence of those facts that creates a news story.

The human mind “first believes, then evaluates,” as one psychologist put it. To that I’d add, “as long as it doesn’t get distracted first.” How can we expect people to transcend their biology while they read celebrity gossip and news about sports? The science shows that not only are we bad at remaining skeptical, we’re also bad at correcting our beliefs when they’re proven wrong.

Once the mind has accepted a plausible explanation for something, it becomes a framework for all the information that is perceived afterward. We’re drawn, subconsciously, to fit and contort all the subsequent knowledge we receive into our framework, whether it fits or not. Psychologists call this cognitive rigidity. The facts that built an original premise are gone, but the conclusion remains—the general feeling of our opinion floats over the collapsed foundation that established it.

In another study researchers examined the effect of exposure to wholly fictional, unbelievable news headlines. Rather than cultivate detached skepticism, as proponents of iterative journalism would like, it turns out that the more unbelievable headlines and articles readers are exposed to, the more it warps their compass—making the real seem fake and the fake seem real. The more extreme a headline, the longer participants spend processing it, and the more likely they are to believe it. The more times an unbelievable claim is seen, the more likely they are to believe it.

Lincoln lived long before the internet, but in one of his early speeches he made a warning that echoes to this day: “There is no grievance that is a fit object of redress by mob law.” Especially something dumb somebody said or did when they were a kid!

My test is a little simpler: You know you’re dealing with snark when you attempt to respond to a comment and realize that there is nothing you can say.

Blogs, to paraphrase Kierkegaard, left everything standing but cunningly emptied them of significance.

Andy Warhol once said that he doesn’t read criticism but measures it in inches. I’m much the same way.