More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

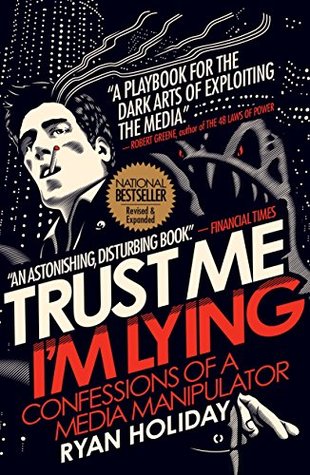

Ryan Holiday

Read between

December 14 - December 25, 2020

There’s nothing fun about being right if what you’re right about is the triumph, or the temporary triumph, of the inevitably bad.

It spins out of control very quickly. There were a lot of names thrown at me and my book, from “douchebag” to “lying jerk” to “out and out phony” to “troll.” One blog accused me of “throwing shit” and another influential PR writer claimed I was “hurting an entire industry.”

“It’s difficult to get a man to understand something,” Upton Sinclair once said, “when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

However the play starts, the end is the same: The economics of the internet are exploited to change public perception—and sell product.

Winston Churchill wrote of the appeasers of his age that “each one hopes that if he feeds the crocodile enough, the crocodile will eat him last.”

It is not news that sells papers, but papers that sell news. —BILL BONNER, MOBS, MESSIAHS, AND MARKETS

I think of blogs and social media as today’s newswires. They’re what poisoned the debate and the clarity of a nation of some 325 million people. They’re how we fell for one of the greatest cons in history.

Radio DJs and news anchors once filled their broadcasts with newspaper headlines; today they repeat what they read online—certain blogs more than others. Stories from blogs also filter into real conversations and rumors that spread from person to person through word of mouth. In short, blogs are vehicles from which mass media reporters—and your most chatty and “informed” friends—discover and borrow the news. This hidden cycle gives birth to the memes that become our cultural references, the budding stars who become our celebrities, the thinkers who become our gurus, and the news that becomes

...more

The economics of the internet created a twisted set of incentives that make traffic more important—and more profitable—than the truth.

Some people in the press, I think, are just lazy as hell. There are times when I pitch a story and they do it word for word. That’s just embarrassing. They’re adjusting to a time that demands less quality and more quantity. And it works to my advantage most of the time, because I think most reporters have liked me packaging things for them. Most people will opt for what’s easier, so they can move on to the next thing. Reporters are measured by how often their stuff gets on Drudge. It’s a bad way to be, but it’s reality. —KURT BARDELLA, FORMER PRESS SECRETARY FOR REPUBLICAN CONGRESSMAN DARRELL

...more

Online publications compete to get stories first, newspapers compete to “confirm” it, and then pundits compete for airtime to opine on it. The smaller sites legitimize the newsworthiness of the story for the sites with bigger audiences. Consecutively and concurrently, this pattern inherently distorts and exaggerates whatever they cover.

It’s a simple illusion: Create the perception that the meme already exists and all the reporter (or the music supervisor or celebrity stylist) is doing is popularizing it. They rarely bother to look past the first impressions.

I am obviously jaded and cynical about trading up the chain. How could I not be? It’s basically possible to run anything through this chain, even utterly preposterous and made-up information. But for a long time I thought that fabricated media stories could only hurt feelings and waste time. I didn’t think anyone could die because of it.

Media companies can very much be in a race against time for growth. Investors want a return on their money and, given the economics of web news, that almost always requires exponential growth in uniques and pageviews. —RYAN MCCARTHY, REUTERS

Bloggers eager to build names and publishers eager to sell their blogs are like two crooked businessmen colluding to create interest in a bogus investment opportunity—building up buzz and clearing town before anyone gets wise. In this world, where the rules and ethics are lax, a third player can exert massive influence. Enter: the media manipulator.

Even though credibility is all you have to sell, it’s not enough anymore. Credibility is not working as a business model. Credibility of journalism is at an all-time low, anyway. —KELLY MCBRIDE, POYNTER INSTITUTE

there is a site called HARO (Help a Reporter Out), founded by PR man Peter Shankman, that connects hundreds of “self-interested sources” to willing reporters every day. It is the de facto sourcing and lead factory for journalists and publicists. According to the site, nearly thirty thousand members of the media have used HARO sources, including the New York Times, the Associated Press, the Huffington Post, and everyone in between.

THE ADVICE THAT MIT MEDIA STUDIES PROFESSOR Henry Jenkins gives publishers and companies is blunt: “If it doesn’t spread, it’s dead.” With social sharing comes traffic, and with traffic comes money. Content that isn’t shared isn’t worth anything.

Angry enough that you must let the author know how you feel about it: You go to leave a comment. You must be logged in to comment, the site tells you. Not yet a member? Register now. Click, a new page comes up with ads all across it. Fill out the form on the page, handing over an e-mail address, gender, and city, and hit “submit.” Damn, got the captcha wrong, so the page reloads with another ad. Finally get it right and get the confirmation page (another page, another ad). Check e-mail: Click this link to validate your account. Registration is now complete, it says: another page and another

...more

social media isn’t a set of tools to allow humans to communicate with humans. It is a set of embedding mechanisms to allow technologies to use humans to communicate with each other, in an orgy of self-organizing. . . . The Matrix had it wrong. You’re not the battery power in a global, human-enslaving AI, you are slightly more valuable. You are part of the switching circuitry

Newspapers are owned and published by rich men. Rich men all belong to the same club. Sure, there’s competition—hard tough competition for circulation, for newsbeats, for exclusive stories. Just so long as it doesn’t damage the prestige and privilege and position of the owners.

A status update that is met with no likes (or a clever tweet that isn’t retweeted) becomes the equivalent of a joke met with silence. It must be rethought and rewritten. And so we don’t show our true selves online, but a mask designed to conform to the opinions of those around us. —NEIL STRAUSS, WALL STREET JOURNAL

If news doesn’t go viral or get feedback, then the news needs to be changed. If news does go viral, it means the story was a success—whether or not it was accurate, in good taste, or done well.

Actions are constrained by income, time, imperfect memory and calculating capacities, and other limited resources, and also by the available opportunities in the economy and elsewhere. . . . Different constraints are decisive for different situations, but the most fundamental constraint is limited time. —GARY BECKER, NOBEL PRIZE–WINNING ECONOMIST

Those who have gone through the high school of reporterdom have acquired a new instinct by which they see and hear only that which can create a sensation, and accordingly their report becomes not only a careless one, but hopelessly distorted. —HUGO MUNSTERBERG, “THE CASE OF THE REPORTER,” MCCLURE’S, 1911

One of the older (leftist) critiques of media is that media is dependent on existing power structures for information. Reporters have to wait for news from the police; they get facts and figures from government figures; they are reliant on celebrities and other news-makers for information. This is a totally valid criticism. It was true in 1950 and it’s really true now.

Most crucially, that machine, whether it churns through social media or television appearances, doesn’t reward bipartisanship or deal making; it rewards the easily retweetable or sound bite– ready statement, the more outrageous the better. —IRIN CARMON, JEZEBEL

Conspiracy theorists like Alex Jones—whose fans are just as rabid as Jezebel’s (if only a bit crazier)—were able to repeatedly ask the same paranoid questions, make enough accusations, and eventually get enough mainstream media attention that some people began to think it was real.

We are the tools of rich men behind the scenes. We are jumping jacks, they pull the strings and we dance. —JOHN SWINTON, JOURNALIST, NEW YORK SUN (1880)

Breitbart, who died suddenly of heart failure in early 2012, might not be with us any longer, but it hardly matters. As he once said, “Feeding the media is like training a dog. You can’t throw an entire steak at a dog to train it to sit. You have to give it little bits of steak over and over again until it learns.” Breitbart did plenty of training in his short time on the scene. Today one of the dog’s masters is gone, sure, but the dog still responds to the same commands.

There is no more Big Lie, only Big Lulz, and getting gamed is no shame. It’s the seal on the social contract, a mark of our participation in this new covenant of cozening. —WIRED

The idea that the web is empowering is just a bunch of rattling, chattering talk. Everything you consume online has been “optimized” to make you dependent on it. Content is engineered to be clicked, glanced at, or found—like a trap designed to bait, distract, and capture you.

According to a Nielsen study, active social networkers are 26 percent more likely to give their opinion on politics and current events offline, even though they are exactly the people whose opinions should matter the least.

Facebook is supposedly one of the largest news sources in the world, and days after the election, it denied that the news it shared could have possibly impacted users’ behavior in a significant way. With manipulative tactics that range from exploiting the so-called attention gap to giving voice to propagandistic campaign surrogates to addictive UX features to editors warping coverage around their own “narrative,” we’re all drowning in a sea of unreality. If the users stop for even a second, they may see what is really going on. And then the business model would fall apart.

Our readers collectively know far more than we will ever know, and by responding to our posts, they quickly make our coverage more nuanced and accurate. —HENRY BLODGET, EDITOR AND CEO OF BUSINESS INSIDER

The web gurus try to tell us that this distributed, crowdsourced version of fact-checking and research is more accurate, because it involves more people. But I side with Descartes and have more faith in a scientific approach, in which every man is responsible for his own work—in which everyone is questioning the work of everyone else, and this motivates them to be extra careful and honest.

Companies should expect a full-scale, organized attack from critics. One that will simultaneously overrun blog comments, Facebook fan pages, and an onslaught of blogs, resulting in mainstream press appeal. Start by developing a social media crises plan and developing internal fire drills to anticipate what would happen. —JEREMIAH OWYANG, ALTIMETER GROUP, WEB-STRATEGIST.COM

Russia is a well-known user of this tactic as well. They call it dezinformatsiya— essentially disinformation via trolling. In the United States we call it “astroturfing”—using fake accounts or supporters to create what appear to be shows of real opinion around the internet. Another word for this is “shitposting”—whenever you see an online conversation suddenly interrupted by what seems like an unhinged person ranting about this issue or that issue.

*In his book The Psychopath Test, Jon Ronson, a journalist, suggests that the real way to get away with “wielding true, malevolent power” is to be boring. Why? Journalists love writing about eccentrics and hate writing about dull or boring people—because it’s boring.

Our web folks will ask, “Can’t we post it and say we’re checking it?” The feeling nowadays is, “We don’t make mistakes, we just make updates.” —ROXANNE ROBERTS, WASHINGTON POST RELIABLE SOURCES COLUMNIST

Bloggers brandish the correction as though it is some magical balm that heals all wounds. Here’s the reality: Making a point is exciting; correcting one is not. An accusation is much likelier to spread quickly than a quiet admission of error days or months later. Upton Sinclair used the metaphor of water—the sensational stuff flows rapidly through an open channel, while the administrative details like corrections hit the concrete wall of a closed dam.

We grow tired of everything but turning others into ridicule, and congratulating ourselves on their defects. —WILLIAM HAZLITT, “ON THE PLEASURE OF HATING” (1826)

Lincoln lived long before the internet, but in one of his early speeches he made a warning that echoes to this day: “There is no grievance that is a fit object of redress by mob law.”

Truth is like a lizard; it leaves its tail in your fingers and runs away knowing full well that it will grow a new one in a twinkling. —IVAN TURGENEV TO LEO TOLSTOY

Entertainment powered television, and so everything that television touched—from war to politics to art—would inevitably be turned into entertainment. TV had to create a fake world to fit its needs, and we, the audience, watched that fake world on TV, imitated it, and it became the new reality in which we lived.

Twitter lacks business focus. Twitter is not a social media platform. It’s part talk radio, part live news coverage, part political commentary. Twitter needs to be streamlined with those business focuses in mind.

The newsroom can never know as much information as the crowd or private network can. There’s a certain necessary occupational arrogance that comes with assuming that a few thousand people can know all the news that’s fit to print. I’m a bit more suspicious. There’s a huge bias toward breaking news. If you can break new news while everyone else is following your lead you can control the future. People are tired of the right-wing and left-wing ghettos.