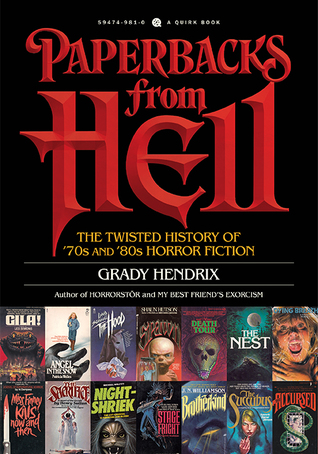

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 20 - December 27, 2022

Though they may be consigned to dusty dollar boxes, these stories are timeless in the way that truly matters: they will not bore you. Thrown into the rough-and-tumble marketplace, the writers learned they had to earn every reader’s attention. And so they delivered books that move, hit hard, take risks, go for broke. It’s not just the covers that hook your eyeballs. It’s the writing, which respects no rules except one: always be interesting.

But a whole lot of authors willingly dipped their toes into the horror waters, with surprising success. Classy Southern novelist Anne Rivers Siddons wrote The House Next Door, which remains one of the best haunted house novels in the genre.

Isobel’s electrifying cover painting is the first horror art sold by Rowena Morrill, one of the all-time greats. Better known for her work in science fiction and fantasy, Morrill also painted covers for a freaky series of Lovecraft reprints from Jove. And she remains the only artist in the field whose work has graced not only the cover of Metallica’s greatest bootleg album (No Life ’til Power) but also the walls of one of Saddam Hussein’s love nests.

Satan Gets Woke

Readers couldn’t get enough books about spooky Catholics. In the wake of The Exorcist, a cry went up from paperback publishers: “Send more priests!” And, lo, did the racks fill with demonic men of the cloth and scary nuns.

The Sentinel was a bona fide money train thanks to a moderately successful movie version that featured an all-star cast (John Carradine is Father Halloran! Burgess Meredith is Charles Chazen! Christopher Walken is Detective Rizzo! Jeff Goldblum is Jack! And Ava Gardner is “the Lesbian”!)

Real-world Vatican infighting always makes for a good plot. Whitley Streiber’s The Night Church depicts a Catholic Church split between a secret cult of Cathars, who are breeding the anti-man to wipe Homo sapiens off the map, and the last surviving vestiges of the Inquisition, who use gruesome blowtorch torture to snuff out the Cathars before their mind-controlled subjects can hump mankind into extinction.

This is the kind of book in which a priest resists fleshy temptation by jamming a nail through his hand, people vomit their souls into toilets, and succubuses ooze black breast milk. And when Joe discovers that the succubus can be destroyed only if she’s decapitated at the moment of orgasm, you know this book is about to go so far over the top it achieves orbit.

The Gilgul doesn’t quite live up to the promise of its cover, however. It honors the beautiful traditions of the Jewish people with the story of a young possessed bride who sprays blood from her nipples.

Red Devil is Yiddish Cold War camp of the highest order, but it feels like yesterday’s cold kugel next to Bari Wood’s deeply felt immigrant love song The Tribe. Wood started her career as an editor for the medical journal CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, which sounds like the most depressing job ever. Later she had hits with Twins (1977), which was adapted into David Cronenberg’s film Dead Ringers (1988), and Doll’s Eyes (1993), adapted into the Neil Jordan film In Dreams (1999).

This is a book about tribes—found families who put their backs together and face outward, defending themselves against invaders—and how toxic they can become. It’s also a book of grace notes and details. A broken bottle of perfume whose scent still haunts a garage thirty-five years later. An incongruous flowered curtain that acquires menace as the reader slowly realizes what it conceals. And a murdered man whose last thoughts, as he’s stabbed to death on Nostrand Avenue, are not of fighting back but of a trip he once took with his wife. The way she looked, paddling clumsily at the bow. Of her

...more

Subtlety and understatement are not words normally associated with a genre whose covers feature skeleton cheerleaders and hog-tied babysitters, but those qualities are the hallmarks of the six books written by Ken Greenhall (including two under the pseudonym Jessica Hamilton). His characters sit down across from you and tell their stories in measured, reasonable tones. Greenhall writes about animal attacks, witchcraft, serial killers, human sacrifice—and of course, homicidal children—without ever raising his voice.

The Only Good Magician Is a Dead Magician Hating clowns is a waste of time because you’ll never loathe a clown as much as he loathes himself. But a magician? Magicians think they’re wise and witty, full of patter and panache, walking around like they don’t deserve to be shot in the back of the head and dumped in a lake. For all the grandeur of its self-regard, magic consists of nothing more than making a total stranger feel stupid. Worse, the magician usually dresses like a jackass.

Mazes and Monsters is best remembered today for its TV movie adaptation, which aired in 1982 and featured Tom Hanks in his first leading role, as Pardieu the Holy Man, freaking out on the streets of New York before trying to jump off the World Trade Center.

1974 was pop culture’s Year of the Animal. First came Jaws by Peter Benchley, a novel about a stressed-out great white shark suffering from portion control issues.

Robert Marasco’s Burnt Offerings (1973), a chilling tale about a family who escapes the city to move into a summer rental…from hell. Marasco was a high school English teacher, so his illusions about human nature had long ago been stomped to death.

Despite Jackson’s iconic The Haunting of Hill House, Matheson’s go-for-broke Hell House, Anne Rivers Siddons’s beautifully disturbing The House Next Door, and even Marasco’s pioneering Burnt Offerings, the unfortunate fact remains that America’s most iconic haunted house is the title property from The Amityville Horror. Crass, commercial minded, grandiose, ridiculous, this carnival barker’s idea of a haunted house is a shame-train of stupid.

The Crazy-Maker Ramsey Campbell will show you terror in a plastic bag. Or a pedestrian underpass. Or a deserted council estate.

Campbell’s stories feel like week-old newspapers, swollen with water, black with mold, forgotten on the steps of the abandoned tenement. His

Campbell writes the way schizophrenics think (he’s said that for most of his life, his mother showed signs of schizophrenia). He doesn’t want to describe actions; he wants to alter perceptions. His descriptions are full of visual miscues and the confusion of organic verbs with inorganic nouns. Living creatures behave like automatons, inanimate objects sprout and grow as if alive, personalities are overridden and replaced, the familiar is described in ways that make it seem alien and threatening. Giving oneself over to Campbell’s writing feels a bit like losing one’s mind. Sounds are

...more

Paperbacks of the ’70s had been shaped by grim, sober novels like The Exorcist and Rosemary’s Baby. By contrast, horror fiction of the ’80s was warped by the gaudy delights of Stephen King and V. C. Andrews.

Michael McDowell was an Alabama native whom Stephen King once called “the finest writer of paperback originals in America,” and his Blackwater series is the One Hundred Years of Solitude of the genre. He’d be considered one of the great lights of Southern literature if his books dealt with things other than woman-eating hogs, men marrying amphibians, and vengeance-seeking lesbian wrestlers wearing opium-laced golden fingernails.

Wherever you think this book won’t go, Masterton not only goes there, he reports back in lunacy-inducing detail. By the last page we’ve seen amputee dwarf assassins, flaming dogs, one of the most harrowing scenes of self-cannibalism ever committed to paper, one death by explosive vomiting, and an appearance by Jesus Christ himself. Throughout, Masterton enjoys himself immensely. He cares about his characters. His dialogue is funnier than it needs to be, his gore is gorier, and his sex is more explicit. His books may not be the most tasteful, or consistent, but you feel that Masterson will

...more

Graham Masterton went where lesser writers feared to tread, chronicling madmen living inside walls (Walkers), an apocalyptic grain blight (Famine), an evil chair (The Heirloom), cannibal cults (Feast), and a mirror that witnessed a child’s murder (Mirror).

But the biggest skeleton wrangler of them all was also one of the genre’s best-known editors and most prolific writers: Charles L. Grant. A Vietnam veteran who disliked Lovecraft and hated gore, Grant was a purveyor of what he first called “dark fantasy”—what was later called “quiet horror.”

Made up of the wives of power brokers and politicians in Washington, D.C., the PMRC publicly demanded that record labels reassess the contracts of musicians who performed violent or sexualized stage shows. They managed to hold Senate hearings on explicit lyrics and “porn rock,” which accomplished little except to show Americans that Twisted Sister’s Dee Snider was more levelheaded and informed than Tipper Gore. The group’s only lasting impact was the explicit lyrics sticker on CDs and cassettes, immediately making those recordings one hundred times more desirable to kids. Clive Barker (far

...more

Brautigam, Don (1946–2008) Most famous for his Stephen King paperback covers, Brautigam delivered striking, iconic, sophisticated covers for Cujo, Firestarter, The Stand, and ’Salem’s Lot, plus the hand full of eyeballs on the paperback Night Shift. He’s also the man behind the album covers of Metallica’s Master of Puppets and Mötley Crüe’s Dr. Feelgood.

Straub, Peter (born 1943) Similar in prominence to Stephen King in the ’70s and ’80s, Straub wrote big, fat books that became big, fat paperback best sellers, and he blurbed plenty of other horror writers. He began his career writing literary fiction but started writing horror with his third book, the ghost story Julia (1975); and his fifth book, Ghost Story (1979), was a huge hit. The massive sales are unusual for an elegant, understated writer whose prose is some of the most polished in horror fiction.