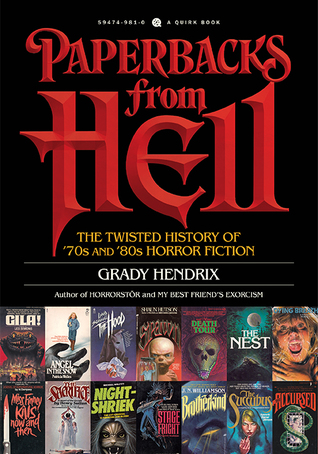

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

August 6 - August 7, 2022

to the moment that the lawyer/fiancé realizes exactly what the Nazi leprechaun named Greta is up to in his pants,

The books I love were published during the horror paperback boom that started in the late ’60s, after Rosemary’s Baby hit the big time. Their reign of terror ended in the early ’90s, after the success of Silence of the Lambs convinced marketing departments to scrape the word horror off spines and glue on the word thriller instead.

These books, written to be sold in drugstores and supermarkets, weren’t worried about causing offense and possess a jocular, straightforward, “let’s get it on” attitude toward sex. Many were published before the AIDS epidemic, at the height of the Swinging ’70s, and they’re unapologetic about the idea that adults don’t need much of an excuse to take off their clothes and hop into bed.

More than any other genre, horror fiction is a product of its time, and the ’60s were a runaway train, smashing through every social value, cultural construct, and national myth at 500 m.p.h., leaving smoking rubble in its wake.

Horror movies responded with polite vampires in velvet capes. Mainstream movies were being mutated by the French New Wave and Akira Kurosawa’s samurai spirit, while biker flicks flipped the bird at square society. Horror movies continued their zomboid shuffle, unaffected by the culture around them.

if horror movies and television shows were stuck in the ’50s, horror publishing was trapped in the ’30s. While mainstream publishers were on fire with books like Truman Capote’s chilling true-crime shocker In Cold Blood, Jacqueline Susann’s titillating Valley of the Dolls, and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, the horror genre was taking its cues from the pulps of yesteryear.

After crashing in the 1950s, the paperback market surged back less than a decade later when college students turned Ballantine’s paperback editions of The Lord of the Rings into a zeitgeist-sized hit. Bantam Books reprinted pulp adventures of Doc Savage from the ’30s and ’40s, adding lush, photorealistic, fully painted covers by James Bama. And there was an early-’60s “Burroughs Boom” when publishers discovered that twenty-eight of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s books had fallen into the public domain.

Between 1960 and 1974, thousands of these covers appeared on paperback racks as gothic romances became the missing link between the gothic literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the paperback horror of the ’70s and ’80s.

Peak gothic was 1960 to 1974, and authors like Barbara Michaels, Victoria Holt, and Mary Stewart sold in the millions. But the tide began to turn in 1972 when Avon editor Nancy Coffey grabbed a manuscript out of the slush pile and discovered she couldn’t put it down. It was Kathleen Woodiwiss’s The Flame and the Flower, and it became the first bodice ripper, a variety of historical romance featuring more explicit passion.

When Gross came up with his idea to publish a line of gothic romances, he drafted a memo to his art director about the covers. “I want a category format that my mother and aunts would be proud to be seen reading,” he wrote. “Make the heroine look like a very refined upper-class blond young woman with good cheekbones….She’s running towards you…behind her is a dark castle with one light in the window, usually in the tower. Make the tower tall and thick. Believe me, they’ll get the phallic imagery.”

Brooding, shadowy mysteries were relocated to the domestic sphere, turning every home into a haunted castle and every potential bride into a potential victim.

The totally macho moniker “Peter Saxon” was a group pen name for a bunch of British authors (W. Howard Baker, Rex Dolphin, and Wilfred McNeilly, among others) who churned out ersatz pulp novels with fully painted covers that looked like all the other pulp reprints on the stands.

The six Guardian books were about square-jawed, tweed-and-blackbriar-pipe types investigating haunted houses, underwater vampires, voodoo cults, and Australians. Sort of like Scooby-Doo, only with more orgies.

They discovered where evil dwelt by dowsing a road map, then zipped off in their Jaguars and Land Rovers to battle Scottish Death Dwarves, voodoo caverns located beneath the streets of London, and sinister covens of Glasgow beatniks.

Underwater vampires are to blame,

Steven Kane has to battle wolves and were-sharks and even lead an army of dolphins against the Drowned City of Ker-Ys before the climactic storming of an ancient castle.

Jeffrey Catherine Jones, the artist behind these decadent covers, got her first gig on an Edgar Rice Burroughs book because she could imitate the dark, doomy dynamism of Frank Frazetta (whose hard-rocking art graced almost every book and album cover of the era). Jones eventually made art for everyone from Screw magazine to DC Comics.

In a little more than five years, horror fiction became fit for adults, thanks to three books. Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, Thomas Tryon’s The Other, and William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist were the first horror novels to grace Publishers Weekly’s annual best-seller list since Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca in 1938.

Horror was for nobodies when Ira Levin—a scriptwriter with a single book (1953’s A Kiss before Dying) and a failed Broadway musical (Drat! The Cat!) to his name—sat down to write a novel about a woman who gives birth to the devil.

Four months after the book hit the stands, Roman Polanski rolled cameras on an adaptation that would earn an Oscar. The film, described as “sick and obscene” by the Los Angeles Times and given a “C for Condemned” rating by the Catholic Church, wound up saving Paramount Studios from bankruptcy.

Fueled by amphetamines and written during a feverish ten-month spree, Blatty’s book was dead on arrival in bookstores until a last-minute guest cancellation earned him a sudden appearance on The Dick Cavett Show.

Four million copies of The Exorcist were sold before William Friedkin’s motion picture adaptation debuted in December 1973 and became a cultural landmark. The film was the second-highest-grossing movie of the year and won two Academy Awards.

Tryon had what People magazine called “a relentlessly mediocre acting career” before he starred in dictatorial director Otto Preminger’s The Cardinal, an experience that drove the future author to a nervous breakdown and made him swear to become a producer so that he could always fire the director.

Rosemary’s Baby started the pot boiling, but the publication of The Exorcist and The Other threw gasoline all over the stove. Whether it was a reprint from 1949, a reissue of Dennis Wheatley black magic books from 1953, or a brand-new novel, soon every paperback needed Satan on the cover and a blurb comparing it to The Exorcist or Rosemary’s Baby or The Other.

Descended from the pulps, occult horror novels at the dawn of the ’70s still felt like places where The Guardians would feel at home. But after The Exorcist hit movie screens in 1974, horror fiction scraped its pulp influences off its shoe like a piece of old gum.

avant-garde writer Hubert Selby Jr.’s book about a serial adulterer, The Demon, displayed a blurb comparing it to Rosemary’s Baby.

Classy Southern novelist Anne Rivers Siddons wrote The House Next Door, which remains one of the best haunted house novels in the genre.

Herman Raucher wrote the landmark coming-of-age novel Summer of ’42 before he delivered his only horror novel, the creepy Maynard’s House, about a Vietnam vet taking on a witch in rural Maine. And William Hjortsberg stayed with literary fiction throughout his career…except for one influential sidestep: Falling Angel.

Somewhere between The Guardians and Michael Avellone’s Satan Sleuth in concept, Hjortsberg’s novel depicts a private investigator who falls through the surface of the waking world into a nightmare of satanic sacrifice.

But Hjortsberg delivered his hardboiled noir straight, tongue nowhere near cheek. P.I. Harry Angel is hired to find a missing jazz singer, Johnny Favorite, who may be trying to pull an insurance scam. As Harry closes in on his target, everyone he interviews is murdered. It seems that Favorite sold his soul to the devil—and is maybe trying to welch on the deal.

The horror isn’t that Harry Angel might be Johnny Favorite, or that Johnny Favorite might have sold his soul, but that Harry Angel might not be who he thinks he is. He may not be a brave World War II veteran. He might in fact be a murderer. Everyone in this book has a double identity, leading to the chilling matter at the heart of all satanic possession fiction: if Satan can get inside us, then maybe we aren’t who we thought we were.

Every book was “better than Rosemary’s Baby,” “more terrifying than The Exorcist,” and “in the tradition of The Other!” Read in the right order, the titles painted a grim portrait of Satan marching from free-spirited young demon to middle-aged ennui: Satan’s Holiday, Satan’s Gal, Satan’s Seed, Satan’s Child, Satan’s Bride, Satan Sublets, The Sorrows of Satan, Satan’s Mistress, Satan: His Psychotherapy and His Cure.

Exorcism featured possession by LSD, The Inner Circle was all about Beverly Hills and movie stars, and The Stigma saw a witch choked to death on a three-foot-long demon dick.

Demonic incubuses and succubuses slithered out of Italian discotheques to send entire apartment buildings into sexual frenzies and to impregnate women with their demon seed. And the most turned-on, now-era, groove daddy of them all was a forgotten hero known as the Satan Sleuth.

Isobel’s electrifying cover painting is the first horror art sold by Rowena Morrill, one of the all-time greats. Better known for her work in science fiction and fantasy, Morrill also painted covers for a freaky series of Lovecraft reprints from Jove.

she remains the only artist in the field whose work has graced not only the cover of Metallica’s greatest bootleg album (No Life ’til Power) but also the walls of one of Saddam Hussein’s love nests.

Call him Troy Conway. Call him Vance Stanton. Call him Edwina Noone, or Dorothea Nile, or Jean-Anne de Pre, or any of the seventeen pseudonyms he used to write his more than two hundred novels. He was Michael Avallone, and by his own estimation he was the “King of the Paperback” and the “Fastest Typewriter in the East.”

When he sees the carnage (worse than “the Tate-Manson killing orgy of ’68”), St. George develops two white streaks in his hair. “The bastards!” rages his lawyer. “They should fall into Hell with no clothes on.” St. George knows who the culprits are: “Hippies, drop outs, draft dodgers, left-wing radicals, right-wing militants, Jesus Freaks, Devil worshippers, generation gappers, motorcycle weirdos—the whole shebang.”

He balances the scales with these cultists (one of whom is “as gay as a green goose when the asses were down”) using LSD and hand grenades.

The Satan Sleuth used karate to take on werewolves and dynamite to take out chic but satanic fashion designers obsessed with short women.

The Succubus is based on the Manacled Mormon, a kidnapping case that rocked London in 1977.

The biggest best-selling true-crime book in history, its tale of life with Charlie was also a gift for horror novelists, providing a new and timely antagonist: the satanic cult. Until then, satanic covens met in basements or wooded glades, slapping at mosquitos who flew up their black robes. They marched around in circles, hailing Satan the way New Yorkers hail a cab, muttering curses and spells in barely remembered high school Latin.

thanks to Helter Skelter, ritual murder became the highlight of the satanic social season.

In Barney Parrish’s The Closed Circle thinly veiled versions of Robert Redford, Elizabeth Taylor, Ann-Margret, and Jackie Gleason pick up hitchhikers and murder them to praise Satan and stay famous.

in The Sacrifice, fabulously wealthy elbow-patch types obtain extended lives via human sacrifice and are defeated only when a fanatically loyal Yale professor becomes enraged that they stole a book from the university library.

One thing all these books had in common, besides a fanatical devotion to the forces of darkness and a phobic fear of private clubs, was that their characters were as white as the driven snow.

The Transformation and The Closed Circle both sport cover art by Ron Sauber, whose gauzy, fluid artwork was a favorite of art directors. Sauber was born and educated in California and then moved to New York City in 1979. Arriving on Halloween, he almost immediately began working for clients ranging from Twilight Zone magazine to children’s book publishers.