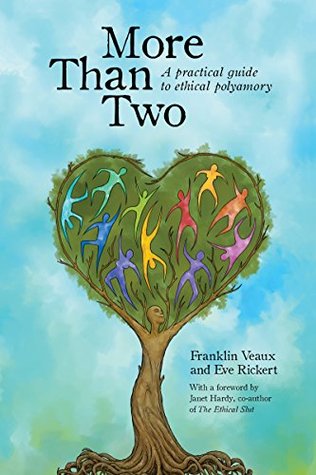

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 5, 2017 - January 16, 2018

Understanding and programming your own mind is your responsibility; if you fail to do this, the world will program it for you, and you'll end up in the relationship other people think you should have, not the relationship you want.

One way to think about (and seek) the kind of relationships you want without objectifying others is to think about what you have to offer (or not). Examples might be: I can offer life-partnering relationships. I can offer intimate relationships that don't include sex. I am interested in supporting a family. I am interested in caring for a family. I am not willing to move from my home for a partner. I have only two nights a week available for relationships. And so on.

Very few of us make it to adulthood without getting a little broken on the way. None of us can see each other's wounds;

We may be able to build walls around deep-rooted fears, insecurities and triggers in monogamous relationships—walls that poly relationships will often raze to the ground.

"After a few days of feeling in free-fall, it's like I suddenly looked behind me and realized…Oh. I have wings."

The longer people avoid confronting that dark night of the soul, the more power it has over them and their relationships. Some people elaborately construct their entire lives to avoid confronting fear. Many people use the hearts of their lovers or their metamours as sacrifices to the unknown beasts they think live within the darkness they're not willing to explore.

We learn courage by taking a deep breath, steadying ourselves, and then choosing the difficult, scary path over the easy way out.

Insecurity is toxic. You can't trust what you're always afraid of losing. You can never become a full partner in a relationship you do not believe you "deserve." You can never embrace happiness if you do not believe you are good enough for it.

For many of us, the kind of vulnerability that comes with letting in deep, heartfelt joy is a little scary.

Our distress may be compounded by the cultural script that says if you aren't torn apart by the thought of losing a partner, it means you don't really love them.

This is all a bit ironic, because the truth is that we will lose everything. Every one of our partners, friends, family members, everything that brings us joy will one day leave our lives—either through life's normal uncertainty and change, or through the inevitability of death. So we have two choices: embrace and love what we have and feel joy as deeply and fully as we can, and eventually lose everything—or shield ourselves, be miserable…and eventually lose everything. Living in fear won't stop us from losing what we love, it will only stop us from enjoying it.

Compassion is not politeness, and isn't even the same as kindness. It's not doing good deeds for someone while quietly judging them! Compassion engages your whole person, and it requires vulnerability, which is part of what makes it so hard. We have to be able to allow ourselves to be present as an equal with another person, recognize the darkness in them and accept it—and that forces us to embrace, as well, the darkness within ourselves.

The skill of expectation management means more than trying to navigate between reasonable and unreasonable expectations. It means recognizing that a desire on my part does not constitute an obligation on your part. And we can never reasonably be upset at someone for failing to live up to our expectations if we haven't talked about our expectations in the first place.

In practice, triangular communication leads to diffusion of responsibility. It becomes easy to tell one partner, "I can't do what you want me to do because Suzie might not like it," rather than "I am choosing not to do what you want me to, because I think Suzie might not like it." (Veto is arguably an extreme example of this diffusion of responsibility. More on this.)

I realized then that regardless of his reasons, it was Ray who was canceling dates. Ray who wasn't giving me the time or attention I wanted. Ray who I needed to talk to about what I needed in the relationship, and Ray who could agree whether or not to provide it. This was an epiphany for me, and one that turned around my relationship with Ray. It simply hadn't occurred to me before to see Ray as the copilot of our relationship.

Active listening involves asking genuine, open-ended, non-leading questions, then listening quietly to the answer, and then repeating back what you heard so it's clear that you heard it correctly,

Asking for what we need, rather than what we think might be available, is kind to our partners, because it communicates what we want authentically—as long as we are ready to hear a no.

It also requires that we look inside ourselves and think about why we want what we want. This can be difficult. "Because I just don't want that" is not good communication. If we ask for something, especially something that places limits on someone else's behavior—and most especially if it affects more people than just you and your partner—we need to talk about the "why" as well as the "what." This more effectively advocates for our needs, and it opens the door for a genuine dialogue in how to have them met.

We feel what we feel; the secret is to understand that we still have power even in the face of our feelings. We can still choose to act with courage, compassion and grace, even when we're terrified, uncertain and insecure.

recovery from a mistake depends on being able to see our partners as human beings doing their best to solve a problem rather than as caricatures or monsters.

With emotional boundaries, we have to take care to not make others responsible for our mental state. When we tell another person, "Don't say or do things that upset me," we are not setting boundaries; we are trying to manage people whom we have already let too far over our boundaries. If we make others responsible for our own emotions, we introduce coercion into the relationship, and coercion erodes consent.

One way to damage a relationship is to believe that your sense of self or self-worth comes from your partner or from being in a relationship.

I give, and you give, and we draw lines in ourselves where we stop. I draw a line here, do you see it? It's the place just before it hurts me to give, because I know, if you love me, if you love the way I do, this is where you would beg me to stop. That poem, and some other things that happened to me around that time, helped me realize that loving someone—or giving to someone—is not supposed to hurt. And if it does, something is wrong.

We have a right to decide whether we will become—or remain—romantically involved with someone who suffers from depression, anxiety or any other psychological illness.

but…sometimes we meet a new person who highlights the flaws in an existing relationship and teaches us that there's truly a better way to live.

As long as you act with integrity and recognize your partner's right to make choices, without controlling or manipulating him, you are not responsible for your partner's relationship with his other partners. You are not to blame simply because you have added value to another person's life.