More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Started reading

April 8, 2019

Illinois. I’d exhausted every published resource, so I needed to dig into the primary documents. I wanted to read their letters and diaries to find out what the Inklings themselves had to say about the group. I wanted to study the manuscript pages, searching for evidence that might be hidden in the margins.

Lewis has complained that there is too much dialogue, too much chatter, too much silly “hobbit talk.” According to Lewis, all this dialogue is dragging down the story line. Tolkien grumbles. “The trouble is that ‘hobbit talk’ amuses me … more than adventures; but I must curb this severely.”

(I wonder—would The Lord of the Rings have been nearly so popular if the main character had been called Bingo all along?)

more than just names have been transformed. The revised version is shorter and much clearer, too. It takes Tolkien 211 words to cover this material in the draft, but only 162 words in the revised version. What’s even more striking is how the proportions of narrative and dialogue have changed. When Tolkien rewrote this material, he cut nearly half of the dialogue. Tolkien’s work in these paragraphs is typical of his work on all three of these beginning chapters. Page after page, he cuts out long conversations, and he picks up the action. Even though he personally prefers a story with much more

...more

small but elegant refinements through...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Tolkien revises and improves his material constantly, and many different readers offer input along the way. As I did my work, it was tempting to try to document all of these changes and chase down all of these influencers. But I wanted to find out what the Inklings said, and I wanted to figure out what difference it made. So I tried to stay focused. In looking at these early chapters, I traced the impact of one specific comment. Lewis told Tolkien to cut down the dialogue. Did he? Yes, without question. The changes in the manuscript show he did. And the timing of events shows that Tolkien was

...more

I wasn’t prepared for just how important this group was, how essential it had become to the work of these writers. I thought that being an Inkling was probably helpful and encouraging. But I was starting to see that the group was, somehow, necessary.

I spent 23 years sifting through letters and studying drafts. I presented my findings in a book called The Company They Keep: C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien as Writers in Community. That book changed the way we talk about these authors because it showed how much the Inklings influenced each other as they worked together week after week.

DOING WHAT THEY DID: Evidence of creative breakthrough is found in unlikely places: a quick note, an offhand remark, a journal entry, or a formal letter. We gather the scraps, and we piece them together the best we can. The fact is, creativity itself is a messy business. We want to think of it as linear and efficient, but in actuality, it is full of false starts, dead ends, long hours, setbacks, discouragement, and frustrations. Knowing that it works this way can help us be more patient with our own untidy processes.

Lewis said that meeting Tolkien triggered two of his childhood prejudices. He explains, “At my first coming into the world I had been (implicitly) warned never to trust a [Catholic], and at my first coming into the English Faculty (explicitly) never to trust a philologist. Tolkien was both.”

Oh, how our opposites can rub us but, if we hang in there, can rock-tumble us into a gleaming, smooth stone

the writing life can be an emotional roller-coaster ride. The excitement of creating is followed by desperate self-doubt. Courage and inspiration compete with discouragement and despair. For innovators in general and for writers in particular, one of the most valuable resources in the midst of these challenges is the presence of resonators.

What is a “resonator”? The term describes anyone who acts as a friendly, interested, supportive audience. Resonators fill many roles: they show interest, give feedback, express praise, offer encouragement, contribute practical help, and promote the work to others.

The presence of resonators is one of the most important factors that marks the difference between successful...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Resonators show interest in the work itself—they are enthusiastic about the project, they believe it is worth doing, and they are eager to see it brought to completion. But more importantly, they show interest in the writer—they express confidence in the writer’s talents and show faith in his or her ability to succeed. They understand what the writer is attempting. They catch the vision a...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Resonators are encouragers. Tolkien recognized this essential gift, expressing thanks to C. S. Lewis: “He was for long my only audience. Only from him did I ever get the idea that my ‘stuff’ could be more than a private hobby. But for his interest and unceasing eagerness for m...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

audience. They help move the text from the private sphere to the public sphere. As they eagerly anticipate new chapters, resonators inspire—or compel— the writer to produce new text in response. They pressure, push, and persuade the writer to bring long-term projects to a conclusion. And their enthusiasm for what has been done in the past may be just what it takes to encourage the writer to tackle brand-new projects.

Something Dan Ray gave me kudos for re: the Hubble Narnia project and Cultural Apologetics book interview this week (3-28-19)

Resonators offer their support in a number of different ways, and the most obvious one is praise.

For Lewis, praise is not only a natural part of life, but also one of the most important traits of a healthy mind. He observes, “The humblest, and at the same time most balanced and capacious, minds praised most, while the cranks, misfits and malcontents praised least.” He sums it up this way: “Praise almost seems to be inner health made audible.”

not merely offering general feedback, but investing significant energy to offer praise in detail.

Williams clearly appreciated Lewis’s enthusiasm—he comments in his letters that Lewis is the one person who really understands him.

“It was a beautiful sight to see a whole room full of modern young men and women sitting in that absolute silence which can not be faked, very puzzled, but spell-bound.”

This is, or would be, the epitome of the effect I'd love to have on young adults.

Was Lewis over the top or over the moon? Well, if he "got" Williams and if it were like our day in any way--inanity laced with profundity even in a major school--maybe not. But what would be the harm unless it was pretentious? A bit of hyperbolic praise can send a relational as well as content-related message.

Not all of their feedback was this detailed or extensive.

All of the Inklings encouraged one another, but Charles Williams seems to have been uniquely gifted at it.

Williams brought a unique quality to the Inklings, to the classroom, to personal relationships, and to his workplace. What was the exact nature of this transforming presence? Gerard Hopkins puts it this way: “He found the gold in all of us and made it shine.” Although all of the Inklings were quick to praise, Williams charged the very atmosphere with praise and encouragement wherever he went.

A desperately needed and wonderful thing to pursue for the rest of my life. I used to be this way much more. I need to re-emerge from my cave and stop grousing and frowning. I must use my gifts of discernment and intuition to see the gold, pray for others, and praise them too. Praising God is the ultimate, but maybe in doing all this, I'm praising God.

A word of praise, a publisher, and a looming deadline were the ingredients Tolkien needed in order to bring that project to a close.

Tolkien was “dead stuck.” Then, on 29 March 1944, he had lunch with C. S. Lewis. Lewis provided encouragement in two different ways. First, he shared his own work in progress. Tolkien records, “The indefatigable man read me part of a new story!” In the act of sharing his own work, Lewis challenged Tolkien, providing more than a hint of friendly rivalry. But Lewis also goaded him directly, urging him to get back to work

“I have seriously embarked on an effort to finish my book, & have been sitting up rather late: a lot of re-reading and research required. And it is a painful sticky business getting into swing again.”

From that time, Tolkien reports steady, significant progress and records that Lewis and the others offered frequent praise for the chapters he read at Inklings meetings. Resonators made the difference.

Carpenter says that Tolkien very nearly abandoned the whole project and confirms that his decision to press on was “chiefly due to the encouragement” of C. S. Lewis.

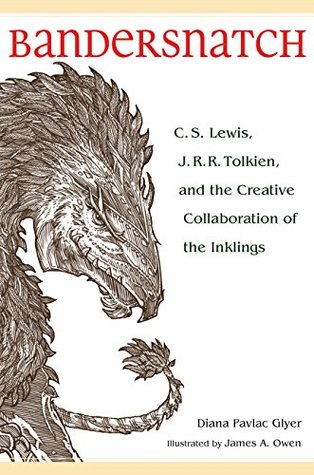

“No-one ever influenced Tolkien—you might as well try to influence a bandersnatch.”

“But for the encouragement of C. S. L. I do not think that I should ever have completed or offered for publication The Lord of the Rings.”

“Tollers, there is too little of what we really like in stories. I am afraid we shall have to try and write some ourselves.”

Númenor as a distinct part of Tolkien’s mythology “arose in the actual context of his discussions with C. S. Lewis.” There is more. Tolkien suggests that The Lord of the Rings itself was the result of this single conversation, this famous wager.

We tend to think of writers creating their work from deep wells of personal inspiration. But often a creative spark is struck from some kind of external circumstance. The Inklings received ideas and motivation from a number of outside sources—Tolkien’s publisher asking for another Hobbit book, for example, or Lewis’s publisher asking him to write something on the problem of pain, or the wager between Tolkien and Lewis. Charles Williams regularly sought suggestions for new projects.

Major Lewis’s book the best entertainment of the evening. This literary dabbler found the atmosphere of the Inklings contagious. Warren Lewis became an active, accomplished author due to the modeling of the group.

He records with some wonder, “Not so bad for a complete amateur who was over fifty eight when he turned author!” He tells us that his brother had urged him to try his hand at writing earlier. But as it turned out, his career as an author was to flourish later, within the context of a supportive and active group.

Most writers find it easier to write when they have specific deadlines. When they meet in a group, each meeting provides accountability.

The Inklings adjusted what they said and how they said it in anticipation of the questions, concerns, biases, and tastes of this ever-present audience.

I find myself always putting it in the form of a question to myself: Is this something that Jack could knock down? Is it something which is proof against any objection he would raise?”

There is something of a parallel between Tolkien’s The Silmarillion and Lewis’s The Pilgrim’s Regress: both are among their authors’ least accessible texts, and both were written apart from the Inklings. Lewis himself recognized the difficulty of his book.

We can credit the Inklings for serving as a lively, interested audience. They helped both Tolkien and Lewis learn how to write for general readers in the many books that followed.

Crucial unless merely diarying. I love abstraction but most hate it. I need the constant “I don’t know what you mean” cause maybe I don’t really either

The role of a resonator is capacious and powerful, and yet, very often it is lived out in small and rather ordinary ways: paying bills, running errands, providing meals, buying books, handling mundane chores, typing or retyping texts, and sharing research materials or study space.

The Inklings lavished considerable time and talent on each other’s work in progress. This may have been something as simple as purchasing copies of the work.

They also shared books with one another. Nevill

him before he returns it to me.” Furthermore, the Inklings made it a habit to recommend books to others.

Lewis enjoins his friend Sister Penelope, “Do you know the works of Charles Williams? Rather wild, but full of love and excelling in the creation of convincing good characters.”

They also wrote and published more than forty reviews in order to promote their work to the largest possible audience. Williams wrote many reviews, including two different endorsements of The Screwtape Letters. One was published in The Dublin Review.