More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Started reading

April 8, 2019

These and other references to the background mythologies of the story testify to Lewis’s familiarity with this larger body of work. They also show Lewis giving generous praise to Tolkien in the area where Lewis himself struggled, the development of a detailed and internally consistent sub-created world.

“The value of the myth is that it takes all the things we know and restores to them the rich significance which has been hidden by ‘the veil of familiarity.’ The child enjoys his cold meat (otherwise dull to him) by pretending it is buffalo, just killed with his own bow and arrow. And the child is wise. The real meat comes back to him more savoury for having been dipped in a story.”

Lewis shows more than mere enthusiasm for this work; he knows it intimately, understands it fully, loves it deeply, explicates it faithfully, defends it fervently. It has touched him bone-deep.

To use a phrase much loved by Lewis, the Inklings were “hungry for rational opposition.”

if there is anything that the Inklings express more often than gratitude for encouragement, it is healthy respect for conflict.

Criticism was free, and it could be ferocious. Warren Lewis describes their conversations as “dialectical swordplay” and tells us, “To read to the Inklings was a formidable ordeal.” The language of fighting and warfare is everywhere. Owen Barfield asserts, “You can’t really argue keenly, eagerly, without being a bit aggressive.” Barfield expresses his experience vividly. He says that in conversation with Lewis, he felt like he was “wielding a peashooter against a howitzer.”

Lewis makes no excuses. He says an aggressive approach is something he learned in school, in what he calls “the rough academic arena.” Lewis spent more than two years studying with William T. Kirkpatrick, a strict, logical, and demanding tutor known as the “Great Knock.” This was undoubtedly one of the influences that shaped Lewis’s appetite for intellectual swordplay. Even praise and appreciation were sometimes expressed using rough, combative language.

Lewis adds, “I’ve a good mind to punch your head when we next meet.”

In dismissing Taliessin through Logres, for example, Havard summarizes it as “a poem of epic dimensions, very Welsh and of an obscurity beyond belief.” Elsewhere, he confesses “when it came to reading his work, I couldn’t understand a word of it.” Hugo Dyson, never one to mince words, scorned Williams’s poetry as “clotted glory from Charles.”

When Williams sent Lewis some of his poetry, Lewis responded: “You will not be surprised to learn that I found your poems excessively difficult.” He discusses several of them, offering praise, then continues to grumble about others that he “definitely disliked.”

Ordway once studied Williams, of course. She corrected me in front of a group at a conf. when I called her a "Williams Scholar". It wasn't a current study focus, so she did the less bombastic Inklings thing and critiqued me in front of all.

Funny, cause when I critiqued a fellow students very poor work, she gave me the business and totalized me as not having sufficient grace or some such

Lewis concludes this letter unequivocally: “I embrace the opportunity of establishing the precedent of brutal frankness, without which our acquaintance begun like this would easily be a mere butter bath!” The Inklings were committed to avoiding this “butter bath,” and they were intentional in giving real, substantial critique.

“They are good for my mind.”

Apparently, good-natured conflict erupted whenever Barfield and Lewis got together. Tolkien says that Barfield “tackled” Lewis, “making him define everything and interrupting his most dogmatic pronouncements.” When Lewis summarized their relationship in Surprised by Joy, he characterized Barfield as “the man who disagrees with you about everything.” Over time, these intellectual skirmishes lengthened and deepened, becoming more formal and moving to the written page. For about nine years, roughly from 1922 to 1931, they sent letters back and forth, arguing about literature, language, poetry,

...more

One thing stands out in these letters: their arguments were not conclusive. In fact, each one credits the other as having ultimately prevailed. Who won? That is hotly debated. What is unmistakable is this: the “Great War” made a powerful and lasting difference, but not because one of them convinced the other he was right. They listened and they learned. Both Barfield and Lewis clarified their own convictions. They modified their views. They expanded their understanding. Perhaps most importantly, they used these letters, year after year, to sharpen their skills. By exchanging arguments,

...more

In gratitude, Poetic Diction was dedicated to C. S. Lewis. And the dedication itself emphasizes the kind of influence he provided. Barfield thanks Lewis and then quotes William Blake, saying “Opposition is true friendship.”

“Three quarters of my mind is delighted that we are so at one about my discarded chapters; the other quarter is sad about the wasted work. Two months almost thrown away! But perhaps something better may come.”

It is worth noting that Tolkien gives the group credit for bringing about “very great changes” and not just superficial adjustments. All Hallows’ Eve was a deeply collaborative effort.

Sometimes criticism impacts the work at hand; sometimes it changes the author.

Lewis responded to Barfield’s critique with ready agreement: “The devil of it is, you’re largely right. Why can I never say anything once?” He continues, tongue in cheek, piling up illustrations of the very flaw he has just been accused of: “‘Two and two make four. These pairs, in union, generate a quaternity, and the duplication of duplicates leaves us one short of five.’ Well, all’s one.” Lewis continues in lighthearted self-mockery, using this same deliberate repetition in two other places in this letter. Clearly, he’s gotten the message. His reply to Barfield is a classic Lewissian retort,

...more

when Warren Lewis read Lewis’s Problem of Pain, he did not find the arguments compelling, nor the conclusion convincing. He writes, “I’ve never seen any explanation of the problem of pain (not even my brother’s) which came near to answering the question for me.”

Tolkien also expresses dislike for quite a number of Lewis’s books. However, in observing this, several cautions are in order. Tolkien describes himself as “a man of limited sympathies.” Elsewhere, he says bluntly, “My taste is not normal.” His preferences were specific, and his standards were high; in short, there are a lot of books by a lot of different authors that Tolkien did not particularly care for.

“Lewis received much criticism for his preaching, teaching, and writing on Christian topics. Indeed, J. R. R. Tolkien was embarrassed that The Screwtape Letters were dedicated to him.” The reason? Some felt that Lewis, “being neither a theologian nor an ordained clergyman, had no business communicating these subjects to the public.”

Lewis knew all of this, and it caused him much distress. He once told his friend Harry Blamires, “You don’t know how I’m hated.” His determination to defy academic protocol and openly express his Christian faith did more than alienate his friends and colleagues; it proved hazardous to his career. Lewis was passed over for promotion to two “coveted Chairs in English Literature at his university despite his scholarly claim to the appointments.” It seems certain that his religious writing was the reason.

chapters. His strong reaction—”bad as can be,” “almost worthless,” “disliked intensely”—was aimed specifically against this small beginning.

This was perhaps my mistake with Dustin Hammond’s little outline and topic which I severely criticized. He then left the program but no one knows whether it was because of my criticism in part or in whole. But I had a bias against the topic and didn’t like the small beginning to “Bandersnatch here. It wasn’t very fair

Tolkien once told Lewis “it probably makes me at my worst when the other writer’s lines come too near (as do yours at times): there is liable to be a short circuit, a flash, an explosion—and even a bad smell, one ingredient of which may be mere jealousy.”

even though he protests loud and clear, “the evidence is rather against Tolkien here.” Tolkien used allegory in his nonfiction (“Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”), his poetry (“Doworst”), and his fiction (“Leaf by Niggle”). He translated, studied, wrote about, and taught allegory, too.

Tolkien was writing his “new Hobbit” for most of the time that the Inklings were meeting. The book occupied a prominent place, year after year, in the course of their meetings. While the group was generally enthusiastic about it, there were dissenting voices.

When Wain was asked what he thought of Middle-earth, he replied, “The fact is that I don’t think anything of it. It has, and had, nothing to say to me. It presents no picture of human life that I can recognize.”

This universally loved set of books wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea. This kind of amazes me that just shows how different people can be. I think maybe God set it up for Lord of the rings to be popular in later generations in different places and that’s Providence

“If Hugo Dyson is remembered for one thing by Inklings readers, it’s as the guy who didn’t like The Lord of the Rings.” Others clearly agree. A. N. Wilson says that Dyson “felt a marked antipathy to Tolkien’s writings.” And Joe R. Christopher has referred to Dyson as “the anti-resonator.”

It is one thing to criticize an author. It is another to shut him down. There is a difference between conflict and contempt. Dyson delivered an axe blow to the root of the tree. The Inklings were shaken, and they never quite recovered.

The Inklings were involved with one another’s work at the smallest level of detail.

it may be that Lewis inspired Tolkien to prioritize this project in the first place. At this time, Lewis was meeting twice a week to read Old English with undergraduates. He was frustrated with the translations available to him. In a long letter written in 1927, Lewis writes, “I wish there was a good translation of Beowulf.” That’s when Tolkien started working on this project in earnest.

Whether or not this outpouring of advice makes a difference depends on one thing: how fluid writers consider their drafts to be. When Anne Gere did research on writing groups, she found that one of the most important keys to their success is “textual indeterminacy,” that is, the writer’s ability to stay open to the possibility of substantial change. This helps explain the effectiveness of the Inklings. As they met and talked about their work, they viewed each manuscript as a work in progress.

Even their name—the Inklings—hints at fleeting notions, half-formed ideas, and rough impressions. Tolkien explains that they did not read polished, publishable drafts to one another but rather “lar...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

They shared very rough drafts, fully expecting to revise them: sometimes adding, sometimes deleting, and sometimes rewriting the material. They might take all the advice they were given or take only one small part. Sometimes, advice simply served as a springboard to a brand-new idea; at other times, it sparked a reaction in direct opposition...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

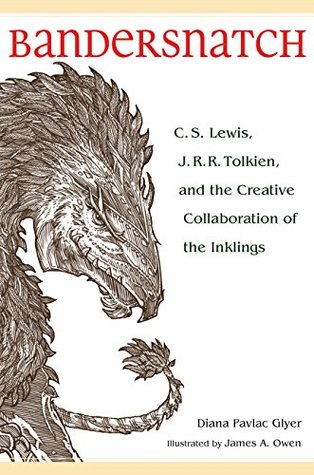

when it comes to listening to criticism, he has been accused of being more ornery than a bandersnatch. But his work constantly evolved, and the Inklings participated every step of the way. Tolkien’s first drafts were dashed off at great speed, and these are the versions he read to the Inklings. At times, they are nearly illegible, breaking off into fragmented notes when ideas flowed faster than his hand could write. Having dashed off a draft, he would rewrite and rewrite and rewrite again. He would continue to produce page after page in order to discover what he wanted to say. As a result, as

...more

This is the kind of inside information that comforts me and actually adds hope to my writing process. I think I’m closer to Tolkien than anyone of the inklings in two ways: one, I write like this into, I can be like a Bandersnatch

Concerning The Lord of the Rings, he declares, “Every part has been written many times. Hardly a word in its 600,000 or more has been unconsidered. And the placing, size, style, and contribution to the whole of all the features, incidents, and chapters has been laboriously pondered.”

“When the ‘end’ had at last been reached the whole story had to be revised, and indeed largely re-written backwards.”

Tolkien was constantly working on the world he had invented. Some of the most foundational aspects of plot and characters kept changing. Even the nature of Middle-earth remained in flux throughout his life.

This tendency to rework his text was part of Tolkien’s personality, a reflection of his preferred writing habits. And the Inklings reinforced rather than restrained this natural tendency.

“I squandered so much on the original ‘Hobbit’ (which was not meant to have a sequel) that it is difficult to find anything new in that world.”

He writes, “I am personally immensely amused by hobbits as such, and can contemplate them eating and making their rather fatuous jokes indefinitely; but I find that is not the case with even my most devoted ‘fans.’” He simply didn’t know where to take the story next. Then on 24 July 1938, he met with C. S. Lewis. Lewis listened carefully to Tolkien’s frustrations with his story. He gave Tolkien a short, clear, transforming piece of advice. Tolkien records, “Mr Lewis says hobbits are only amusing when in unhobbitlike situations.” It was an important insight, and Tolkien took it to heart. As a

...more

No matter how much cultural or imaginative apologetics may really matter, and inspire me in the abstract, if it never matters to readers or teaching audiences at large, it won’t matter much after all. I either need to get a breakthrough like Lewis’s or trick audiences long enough for them to catch on despite themselves